Let’s face it: 2020 was a challenging year for reasons that we all know by heart now. At FII, it was also a year when we (gratefully) witnessed a surge in the submissions we receive from our guest, contributing and commissioned writers, because many of us could afford the privilege of leisure time and the mental bandwidth to think, reflect, rage and write. Just as every other year, the submissions this year too, were rich in intersectional feminist discourse, subversive discussions and debates that got us thinking and hooked as readers. Here are the top 2020 articles from FII that you loved reading this year!

1. Social Media Influencers: Serving Classism, Selective Feminism & Monolithic Nationalism by Savitha Ganesh and Purvi Rajpuria

Considering that social media influencers such as Komal Pandey, Shreya Jain or the Nandy sisters have a large numbers of followers online, the article analyses where they come from as well as the overt and covert messages their videos carry. While social media might appear to be a democratic space that allows independent creators to have a voice, dominant caste sensibilities find their way into the content they put out. Although aestheticised to seem harmless, these dominant caste sensibilities align with a larger Hindu nationalist discourse at the forefront of contemporary national politics. Not only do audiences fail to problematise the content they’re consuming, but they also often celebrate these videos and their aesthetics as women empowerment.

2. Sexualising & Policing Women—Kerala’s “Blue-Saree Teacher” Case by Vinita Teresa

When the Kerala government rolled out a first-of-its kind series of online classes on Jun 1, 2020, many of the sessions were led by female government-school teachers, all of them, irrespective of age, dressed in sarees in conformity with the traditional professional attire of female school and college teachers in Kerala. They made headlines for both the right and wrong reasons. Within hours of the classes going on-air, many online trolls started circulating memes and clips of a particular female teacher in a blue saree; “blue saree teacher” fans and clubs mushroomed all over social media, and in a blatant disregard for privacy, the name and photograph of the teacher got widely circulated.

They generated comments ranging from admiration for the teacher’s good looks and expression of their romantic interest to outright objectification of her body.

3. In Conversation With Ambedkarite Activist Suvarna Salve by Shivani Chunekar

Suvarna Salve is the lead activist and singer of ‘Samta Kala Manch’, an Ambedkarite cultural troupe and the cultural wing of Republican Panthers Caste Annihilation Movement. The Mumbai police had classified Salve as a “habitual offender” and booked her along with other activists for protesting against the violence in JNU earlier in 2020. In the notice against Suvarna Salve, the Mumbai police had also demanded a surety of Rs 50 lakhs from her. Now as the whole country erupted in protests against the rape of the Dalit girl in UP’s Hathras, 24-year-old Suvarna Salve was served a legal notice at her doorstep on October 2 by the city police that prevented her from taking part in any of the protests in the city.

4. Geoengineering & Its Gendered Effects: A Case For Feminist Scientific Leadership by Tanishka Sachidanand

Over the years, ecofeminists have raised concern over geoengineering’s hyper-masculinist approach towards addressing the climate crisis. Ecofeminists have pointed out that geoengineering would severely impact natural-resource dependent communities in developing countries, especially women from these communities. The current lack of diversity within the field of geoengineering paints a grim picture of future inequalities; it foreshadows the exclusion of women from future decision-making on a geoengineered earth. Geoengineering, in a way, furthers the imperial legacy of disqualifying those whom imperial governance has always “othered” within humanity. Conceptualised by mostly men from western countries, geoengineering validates the superiority of the ‘western enlightened man’. It makes him ‘take responsibility’ for future decision-making while downplaying expertise from diverse voices within humanity.

5. Photo Essay: #WomenHaveLegs – And The Last We Checked, They Are Hairy Too by Ardra K Sree

Undoubtedly a watershed moment, the #WomenHaveLegs campaign in Kerala was a tongue-in-cheek response to the ‘ankalamar‘ (self-appointed brothers) that women from across the world came together to gift-wrap and give. There was just a tiny problem. The pictures that were posted seemed to take a leaf from the book that hair removal cream advertisements read from. More or less, there was a standardised and conventional representation of women’s feet–as hairless and spotless. How many of us reading this right now do not have a prickly hair or two at least. if not a lush growth of hair on our arms and legs?

6. Dalit Trauma: Why It Is Important To Address Its Intergenerational Aspect by Priyanka Singh

The recent Hathras gang rape case created a furore in the mainstream media and on social networks only to highlight an issue that has been staring at us for far too long. In 2020, if we are still having to establish the pervasive nature of caste within our social structures, then our progress as a people is debatable. To the savarna eye, caste may not exist; it is the Dalits (which literally means oppressed or broken) who have felt the sting of this societal and systemic oppression in their bones for thousands of years, and has now translated into what could be referred as the intergenerational Dalit trauma.

7. Taking Up Space: Any Match For A Disabled Bride, Sima Aunty? by Anusha Misra

In her article, Anusha asks some hard-hitting questions: “From my standpoint of a young womxn with disability, it did not take me a lot of time before facing the question – “What would Sima Taparia have said about me if I hired her as my matchmaker? How would she describe me as? A short, fat, and disabled bride? In other words, impossible to match with?” She would have probably hoped that my lack of flexibility is the most challenging trait she would have had to deal with.”

8. ‘Love Jihad’: Tracing The Portrayal Of Women As ‘Wombs’ In Hindu Nationalist Politics by Dr Tuli Bakshi

The bodies of women have always been a site for claiming community homogeneity and honor, irrespective of religion, sect, or caste. In this love-jihad issue, they are being re-inforced as essential subjects of the imagined “Hindu Rashtra”. The elopement and conversion of Hindu women are associated with Hindu female purity. This purity is directly linked to Hindu male virility that would reaffirm itself in a public-political domain. It is astonishing that in 2020, a woman is being identified as an exclusive property of the man, and preserving her virtue is becoming a legal prerogative.

9. Why Students Like Jaspreet Kaur Need More Inclusive University Spaces by Riya Gangwal

Jaspreet Kaur – the daughter of a Dalit barber in Punjab’s Mansa village – hit the headlines for scoring 99.5 percent marks in Punjab State Education Board Class XII-Examinations 2019-20. She was planning to enroll as one of the students at Delhi University for higher education after having battled gender disparity, class inhibitions and caste prejudices, which have historically worked to deprive her of even tuitions despite academic genius, and constantly ascribed this merit to mere luck.

10. Rasode Mein Kaun Tha? – The Kitchen As A Site Of Contention in Feminist Politics by Shivangi Deshwal and Sumati Thusoo

Though the Rasode Mein Kaun Tha video went viral for its comical representation, the portrayal of saas-bahu (mother-in-law and daughter-in-law)repertoire or of the women performing domestic chores is quite common in Hindi serials. This onscreen representation bears a strong resemblance to the ground reality in India where women spend most of their time performing domestic chores, with the kitchen being at the centre of it. The article analyses who was in the kitchen: historically tracing how the kitchen has been a site of contention in feminist politics.

11. The Glorification Of The Malayali Male Gaze—5 Years Of Premam by Mythily Nair

Re-watching Premam in 2020, makes one rethink the foundations of my interest in the film. Sure, the nostalgia (or nostu, as affectionately regarded) factor still remains, but where are the intelligent, independent women? How have all 3 women in George’s life been limited to the same banal qualities, of their worth being decided solely through the gaze of a man? Whether it be young-George writing his love letter to Mary, a college-student–George justifying that Malar’s skin imperfections are still beautiful, or the unspoken objectification of Celine through the strategic shots in the “Red Velvet Cake” sequence, where his eye’s trace past her lips as she eats cake. The continued trend of “entho, ennikk kandappozhe ishtayi” (“I don’t know, I liked her as soon as I saw her”) cements that the root of his affections being solely on their external appearance.

12. The ‘Aunty’ Body And All That Follows by Anmol Nayak

The issue with the ‘Aunty’ body arises from a deeply misogynistic and dehumanising understanding of women. In this imagination the woman, whom the world now addresses as ‘Aunty’, has basically served her purpose of marriage and child bearing, and is hence rendered useless. Every other faculty of a woman is deemed irrelevant. The postpartum body is considered unattractive and thus, useless in the patriarchal society. The ‘Aunty’ imagination reinforces the dehumanisation of women – reducing a woman to a conventionally understood attractiveness.

13. Fatness, Womanhood And The Bois Locker Rooms by Tanvee Nandan

If women’s bodies are the location of overtly sexual harassment from a young age, then my fat body was the location of overtly desexualized harassment. When I was 13 and sitting in a class assembly, some students threw branches and leaves behind me and laughed to each other that elephants probably excrete greenery because they eat leaves and branches. Not a particularly clever demonstration, nor perhaps anywhere comparable to what most young women undergo, but nevertheless, it was harassment targeted at my body, and I was subjected to it because I was a woman.

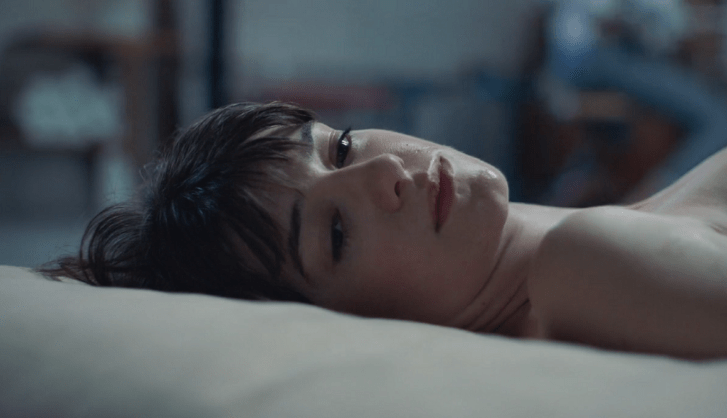

14. Between The Sheets: How ‘Normal People’ Normalises Different Kinds Of Sex & Why We Have Them by Sasha J.

Through the sex that is sometimes tender, sometimes rough and punishing, but always quite sweaty and revealing, we are acutely aware of Marianne’s personal need to simultaneously give, receive, but above all, feel something. Marianne’s experience with men, and the not particularly vanilla sex she has with them, is an honest representation of how people navigate sex for resolutions other than solely pleasure. Normal People compels us to broaden our understanding of how little, or how much, sex can mean and uphold for an individual in what is meant to be a shared moment.

15. Housework And The Normalization Of The ‘Clueless Man’ by Sukanya Shaji

The narrative of the “man who is lost in the domestic space without a woman” is deep rooted in patriarchy and its assignment of gender roles to housework and domestic responsibilities. This kind of nuanced, hidden sexism in our domestic spaces is now becoming more evident in the context of the Covid-19 lockdown. More people at home means more food to be cooked, more clothes to be washed and more similar chores to be done. Women are by default, expected to be in charge of household work even if they have schedules of work that are as hectic or sometimes busier than their male counterparts. They are expected to do it all, despite the presence of men who are equally responsible to participate.

16. Arnab Goswami – Our Prime Time Poster Boy For Toxic Masculinity On TV by Kavin Malini

Arnab Goswami, the editor-in-chief of Republic TV, is a household name in that his news channel has the maximum number of English TV viewers in India. This Oxford University graduate is notorious for functioning as one of the prime propaganda machines of the ruling party and is known to actively muzzle dissent. He “acts as a kind of public scourge for opponents of Modi’s initiatives,” writes Dexter Filkins, an American journalist. He was elected as the President of the News Broadcasters Federation’s governing board. However, he staunchly shirks accountability and peddles disinformation. He’s brazen about his bigotry. He undisputedly takes the cake for having the most overbearing presence on national television. Researching to write this article meant that I had to repeatedly bear witness to him hurling abuses at his panelists, as the latter struggled to get a word in edgewise.

17. Women At Leisure: Photo Essay On Pastime As A Feminist Issue by Surabhi Yadav

Women at Leisure is a photo-project capturing women and girls in carefree moments of leisure, as a measure of freedom and visual reassurance of possibilities beyond restrictions of any kind, even if momentarily. Women singing and dancing together at midnight in a temple to celebrate a deity’s birthday, someone enjoying time by herself in the woods, a girl on a romantic outing with her partner, a group of girls creating a new game or a story – each one of these are moments of them at ease and thus, of defiance.

18. Netflix’s Bulbbul Review — A Feminist Fantasy Or A Feminist Failure? by Megha Mehta

I’ve noticed that on an average, male reviewers have been more critical of the film than female ones. I say on an average, before anybody cherry picks exceptions. The reason for this is apparent once you watch the film. Bulbbul is basically a feminist revenge fantasy. It’s ‘All Men Are Cancelled‘ with a touch of folklore horror. Like Maleficient, the movie subverts the patriarchal trope of the ‘witch’ by reimagining the villainess as a wronged woman. I’m not saying men cannot like the film, but it will definitely make a lot of cisgender-heterosexual men uncomfortable.

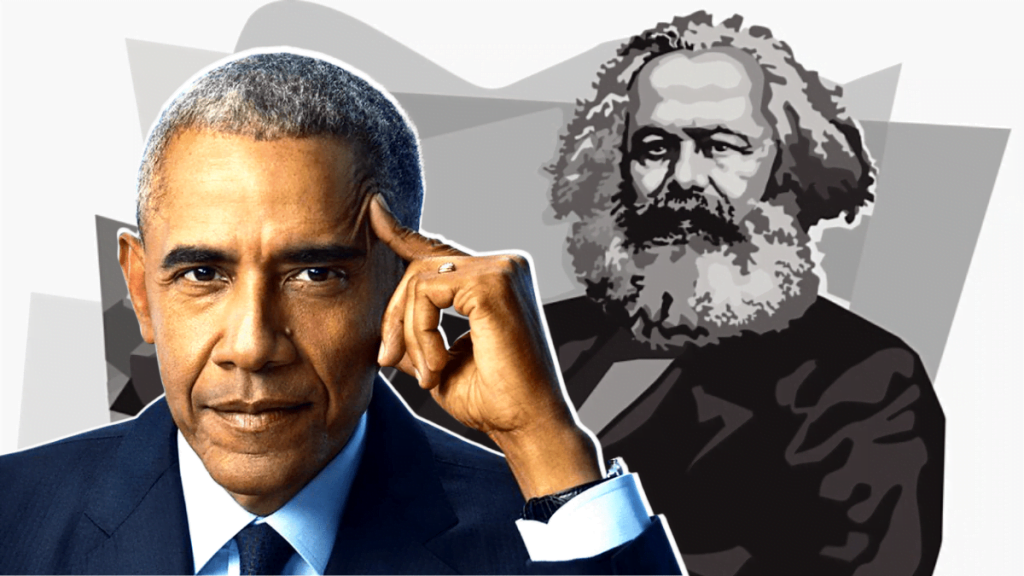

19. The Male Leftist Trope: Yes I’ve Read Marx, Can We Have Sex Now? by Halima Zoha Ansari

Identifying misogyny in a hyper online left has proven to be a monumentally arduous task. They all have a display picture with colours aligned to a cause, the rainbow flag and the hammer and sickle in bio, and a Camus quote in their feed. Maybe if you’re lucky, they’ll condescendingly explain the second wave to you. It’s the woke leftist checklist men perform to gain access to women in leftist online spaces, branding themselves as saviors of all oppressed classes.

20. The Impact Of Covid-19 On Assam’s Women Weavers by Rituparna Patgiri and Ritwika Patgiri

Women who have access to their own income become less tolerant to abuse. The fact that they can earn money, even if it is not much, gives them the confidence to stand up to violence in their homes. At the same time, many of them weave together, and this gives them the initiative to come together. It gives them a feeling of a collective, a platform for solidarity that can help in easing their pain and sharing feelings. But in a world that is marred with COVID-19, India has been in a lockdown and the practice of physical distancing is in practice. This has severely impacted these women weavers who have lost their livelihood and space of solidarity. They have not just lost their source of income but also a zone of comfort. The time that they spend weaving together allows them to come out of their daily lives and talk to each other. As such, their collective spaces are shrinking.

About the author(s)

Feminism In India is an award-winning digital intersectional feminist media organisation to learn, educate and develop a feminist sensibility and unravel the F-word among the youth in India.