In a country whose media landscape is far from neutral, and heavily saturated with fake and sensational news, it becomes critical that a guideline be established for responsible use of language and rights based perspective when covering a beat as sensitive and fundamental as menstruation. A piece of news should spark conversations that help the efforts being made to destigmatise the matter and critique the perpetration of taboos.

Part two of this article delves into why mainstream media must expand on the range of issues covered, follow-up on stories and talk about sustainable menstruation, policy and conflict areas when reporting on menstruation.

Read part one: How Can Mainstream Media Use Inclusive Language To Cover Menstruation Sensitively

1. Focus on the larger systemic gaps

Given the digital era that we live in, the entire approach to covering stories around menstruation can be different. Newslaundry for example, takes up issues that are complex and simplifies them to great detail while not compromising on the many layers of the story. This is done by making their coverage episodic. This story is the first story in a five-part series on the disastrous consequences of the Assam floods and the Amphan cyclone in Bengal.

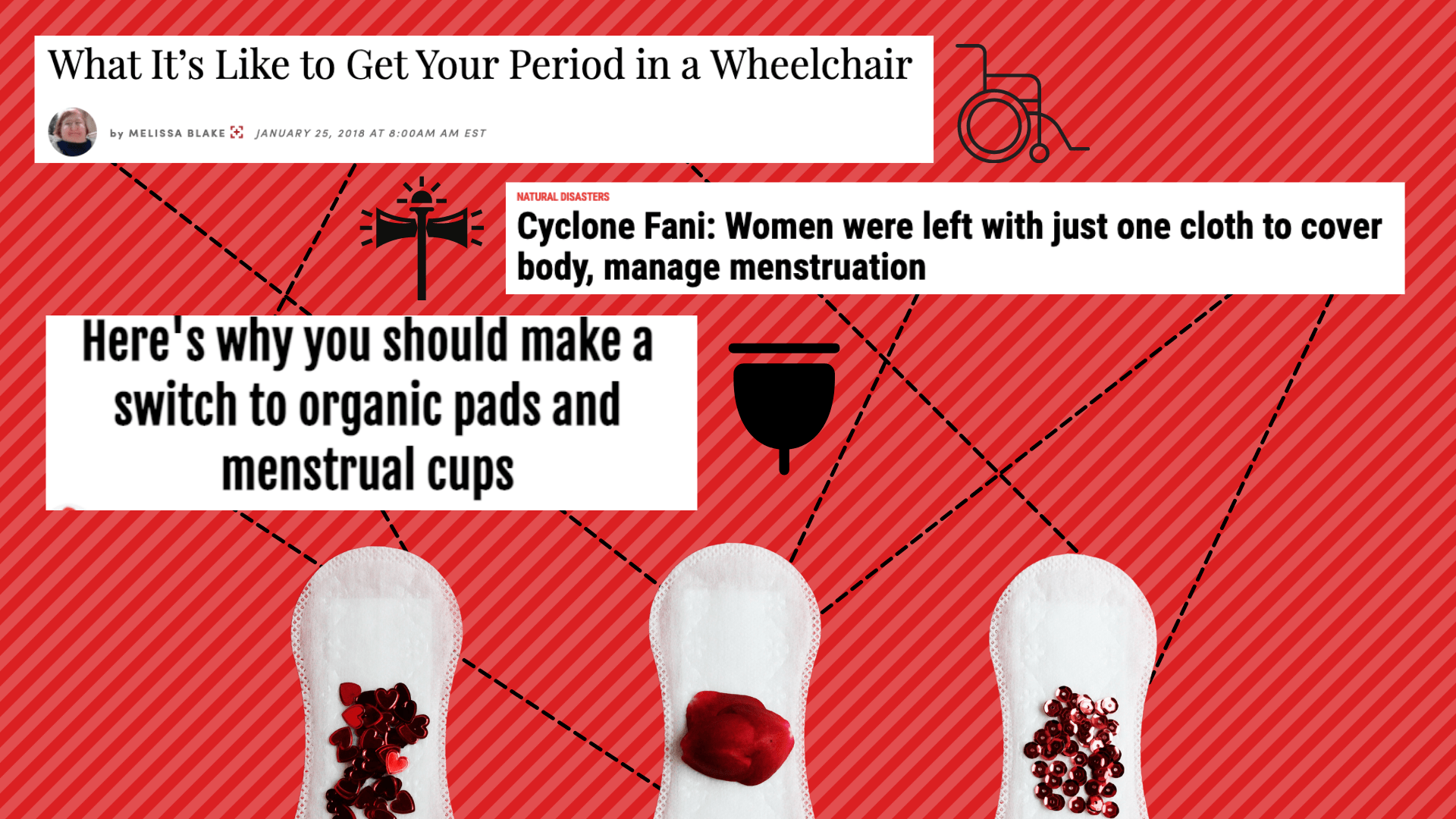

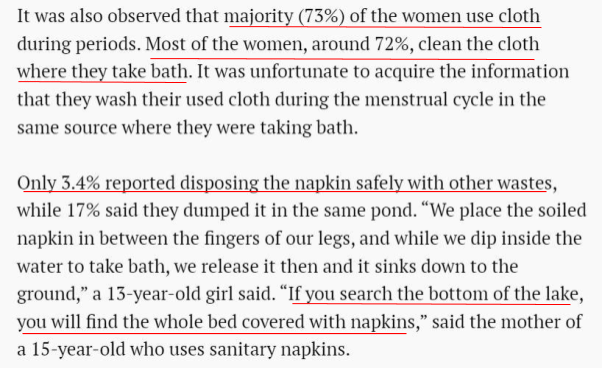

Menstruation as a subject always involves at least three layers, often more: The menstruator, the menstrual hygiene and waste management personnels, and the local government that is incharge of WASH facilities that is available to the menstruator. According to our preliminary research, the media hardly interconnects these layers. An article by Quartz India, talks about how sanitary napkins form the bed of a lake in a village in rural India.

This article talks about a particular village called Chamrabad in Jharkhand. Although it states data and gets quotes from the women in the village, it simply cannot be complete without covering the WASH infrastructure, effects to the water quality, ecosystem and stakeholder responsibility to respond to the crisis in the area.

The infrastructure (sex-separated safe private/communal toilets that are menstrual friendly, disposal mechanisms, water, soaps etc.) affects the MHM in any area, therefore influencing the menstruator’s agency over which products to use. These complexities are largely missed in mainstream media’s coverage.

2. Follow up stories that map progress

Stories that critically follow up on initiatives mark growth. This gives one insight into how far we’ve progressed or how much further we need to go. The Print’s article that analyses every aspect of a Central Government led scheme is one that is rare in the coverage around menstruation.

The article looks at the implementation of the scheme, the awareness around it and also gets comments from important stakeholders involved. These pieces are key in challenging problematic perception around menstruation and giving it a more matter of fact approach.

3. Coverage about sustainable products

If it wasn’t for initiatives/enterprises that advocate sustainable menstrual products, menstruators would be left to simply assume the merits and demerits of using menstrual products.

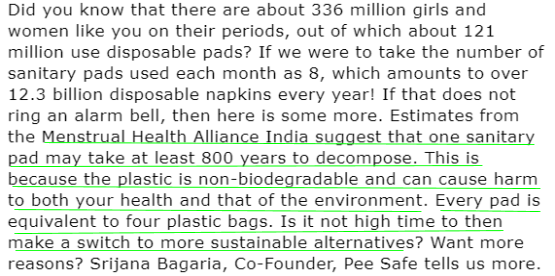

Coming across pieces that advocate shift to organic products without being tagged to World Awareness Days like Environment or Menstrual Hygiene Day like the story attached below is a rarity.

This article on TNIE’s Indulge, however, is an example of one of the very few stories that does advocacy irrespective of the external encouragement. The headline clearly points out that you should make a shift to organic products and goes on to explain why stating data (however, data is not attached) that state that non-biodegradable pads “can cause harm to both your health and that of the environment.” Here also, the language could be ‘suggestive’ rather than ‘imperative’.

Media hardly emphasises agency and control that menstruators can choose to exercise over their bodies through informed choices, especially with menstrual products. Media pieces demonstrated above from She The People often tend to patronise menstruators, especially when it comes to reporting on sustainable products. This issue is systemic as organisations that produce products are themselves not immune to aggrandising, patronising and marketing products as a panacea to ‘menstrual woes’.

The following piece is very brief and lacks commentary from gynaecologists, environmentalists among others. Excerpts ought to guide readers to use a product that suits their individual body’s needs, lifestyles and medical histories. Articles that have such content is meagre.

4. No conversations around Policy

For menstruators in India, the policies that govern their wellbeing is nil. While far and few corporations recognise paid period leaves, there are no policies in place to make menstruation a contextual need and right, for trans persons and persons with disability. The media plays a huge role in catalysing policy changes by creating opportunities for deliberation within the public and private spheres in a society. Extending this influence to menstrual concerns will help amplify the current negligence.

This article in Reuters does not laud the company that offers menstrual leave, fairly so, considering that it should not be treated as a perk but a requirement. This was also an opportunity to zoom out and talk about how menstruators in India have no policy around menstruation at workplaces whatsoever, elaborating on the nuanced need policies and its consequences to unique menstruating body needs, especially premenstrually. Further invisible is the acknowledgement of such extensions to menstruators in prisons, young menstruators in schools and displaced menstruators.

This BBC article, on women being asked to strip at an educational institute in India, is a loud call alerting systemic faults. Unfortunately, the focus is always on such singular incidences, rather than questioning the larger structural negligence. There are very few stories that use a trend to point out the larger problem. Like this report on Hindu Business Line which reads, ‘India needs a menstrual leave policy.’

The complete absence of different lived realities of menstruators (trans, non binary, Dali-Bahujan-Adivasi, Persons with Disabilities) stems from and can also be set right with critical reportage. Discussing workplace menstrual experiences as varied, unique and true to each experience is integral in pushing towards inclusive, holistic policies that go beyond accounting for workplaces/labour laws that have predominantly been designed around male bodies and their lived experiences. Episodes like this demand media’s right to hold an institution accountable post institutional violations. There is hardly any report on follow up of this case, with redressal/punitive actions undertaken.

This US based article written by a woman who served 35 years in jail, covers the poor quality of state provided napkins, monetary shortcomings, inaccessibility of medical help and inhumane treatment. Another article, written by a woman who has a physical disability covers aspects such as non disability friendly products and limited mobility. These are experiences that are yet to be covered by the mainstream media in India.

5. Reportage around menstrual experiences in volatile areas

The reportage around menstrual experiences in disaster management, refugee camps and politically volatile regions like Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh can be counted on the fingers. Stories that highlight the plight of menstruators under such deprived and tense circumstances is imperative to bring meaningful interventions.

This Down To Earth article emphasises the need for a response mechanism to be gender friendly as the lack of it has layered consequences (compromising dignity, safety and health) on menstruators.

Reportage such as these in the mainstream media makes room for well informed response mechanisms.

This piece by the BBC is an instance of good reporting as it that draws emphasis on the most important concern — WASH infrastructure, especially in a disaster prone area.

This piece hopes to evoke and sensitise stakeholders to undertake measures to responsibly report on menstruation, with the limited examples showcased.

Also read: How Did The Civil Society Innovate Menstrual Health And Hygiene Interventions In Lockdown

This article is part of Boondh’s #PeriodsandPatrakaars campaign, whose goal is to enable writers with inputs from various stakeholders (media Houses, journalism students, MHH and waste practitioners, cis menstruators, sports menstruators, vulnerable menstruators including trans, queer, disabled, Dalit Adivasi, prison menstruators, people living with menstrual disorders) with skills to improve the quality of menstrual reporting through a reporting toolkit.

Authors’ Note: This excerpt of suggestions has been structured based on coverage related to menstruation in news and some popular media within India and a few from outside with citation versions of the pieces as on 22nd March, 2020. The goal of these citations is only to drive a point home, problematise the content and not defame the publisher.

If you are a journalist reporting on gender, health or sanitation, do reach out to Boondh via Twitter! To make #ResponsibleRedReporting a reality, your inputs will add great value to this initiative. For details, write to pratyusha@boondh.co

This article has been previously published here.