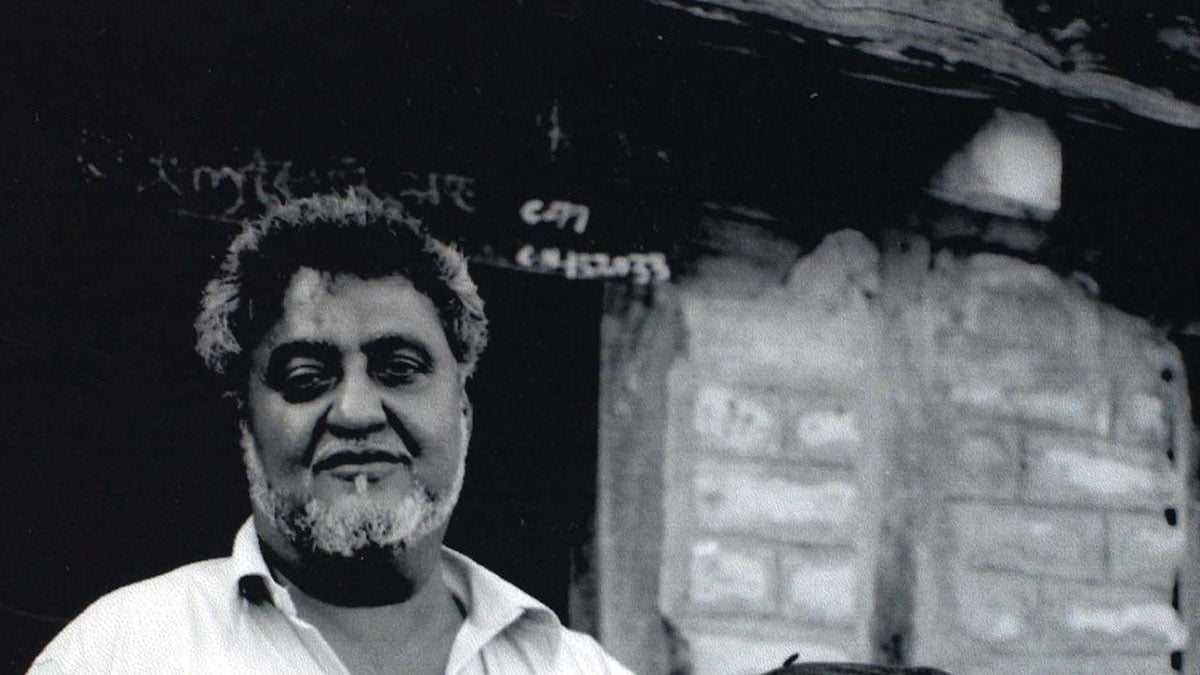

Dalit political history is testimony to Namdeo Dhassal’s immense contribution. He was one of the founders of the Dalit Panther Movement (DPM). Born as a Mahar (whose designated caste occupation was remover of carcasses), he grew up in dire poverty on the streets of Mumbai. He never finished school and was self-taught. His activism, politics, and his art for the fight against the injustice of the caste system made him a beacon of hope for scores of oppressed Dalits. Dhassal is well-known for his audacious poetry for which he won a Padma Shri.

The DPM which eventually became a political party was full of hot-tempered young men that idolized Dhassal for his inflammatory words and actions. Dhassal wrote vivid poems, left nothing to the imagination, and captured the nature of the oppression that he as a Dalit had faced in a chaffed style. For the oppressors, Dhassal was the anti-thesis of the ramifications that upholding the caste system was meant to have- being confident, opinionated, acutely aware of the oppression, and revolutionalizing the masses against that oppression. His use of shock poetry describing the life, subjugation, and helplessness of being Dalit was what drew the masses toward him. Consider these lines from his poem, ‘Equality for All or Death for India‘:

They are fired up with their own egotism

They are possessed by neuroses

Killing, violence, bloodshed

They are polluted by this rotten stench

They make everyone into an Oedipus

They want partition

They want riots

They want to turn humans into demons

They want to see humanity destroyed one more time

Here, Dhassal talks about caste violence and uses the term “they” for caste Hindus, and the “we” is used to denote Dalits. His poems have a historical quality and yet seem very relevant to this day. The imagery and choice of words are unconventional and courageous to say the least.

The DPM was built on the lines of the Black Panthers Movement against racism in the USA of the late 60s. The evolution of the Dalit Panthers journeyed interesting paths. By the late 50s, Ambedkar had decided to renounce Hinduism, the religion which he believed had no conscience. He studied various religions and finally chose to convert to Buddhism as a means of emancipation. He led the mass conversion of millions of Dalits to Buddhism. Ambedkar’s political interpretation of Buddha’s teachings came to be called Navayana or Neo-Buddhism and was the core ideology of the Dalit Panthers when they started.

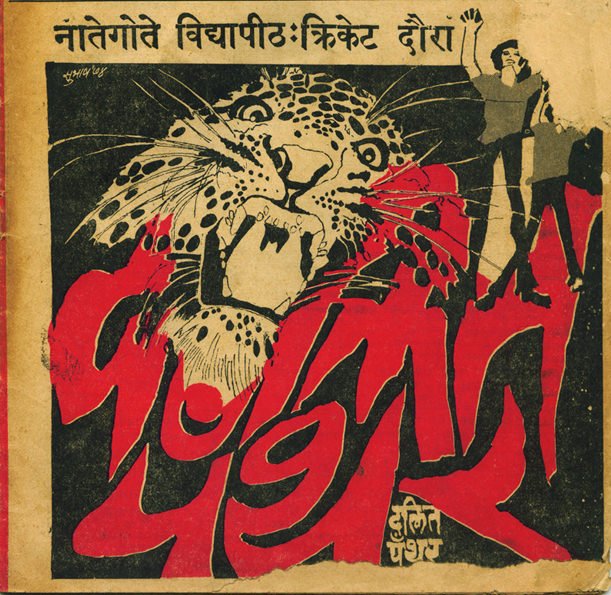

The Panthers movement was initiated by a bunch of college-going Mahar youth whose own families had converted to Buddhism during Ambedkar’s time. The ’60s also saw a wave of new writers on the literary block who were livid with the hegemony of Brahmin writers for not only occupying the literary space but for also appropriating Dalit experiences. The DPM was first born as a literary movement and then went on to become a political movement. Dhassal was a poet before he became an activist and his poetry reflected the raw and shuddering experiences of Dalit oppression in the vocabulary of Dalits.

Also read: Dalit Panthers: A Radical Resistance

The word Dalit means downtrodden. The Panthers decided to use the term because it is casteless and their ideological stand was to fight for all the oppressed be it members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes, the Neo Buddhists, the workers, the landless, poor farmers, women, or then those who were fraught in the name of religion. They called themselves the Panthers after the Black Panthers, which symbolized courage. They believed that violence in response to violence and other forms of oppression was justified. The Dalit Panther’s Party was initially an interesting amalgamation of different ideologies which was no doubt refreshing but which was also the very reason for their split into different styles of leadership many years down the line.

To build this movement from its inception as a literary one to the point where it became a full-fledged social movement and eventually even a political party, the Panthers used a lot of symbolism such as protest marches, demonstrations, pamphleteering, and many times ingenious sloganeering. Public gestures like the burning of the Manusmriti and Gita were carried out to denounce the religious sanctity of the caste system. They commemorated the valorous act of Dalits at Bhima Koregaon War and also held a large rally on Ambedkar’s death anniversary at Chaitanya Bhoomi. All these symbolic acts stimulated the Dalit youth and helped snowball the movement to spread all over the country.

Dhassal was a natural leader full of charisma. People flocked around him, paid rapt attention to his words, were mesmerized by his blasphemous poetry, and saw in him a future of hope and change. Under his leadership, Dalit politics saw a new horizon and was instrumental in unifying the masses. That is why it is soul-crushing to read his wife, Mallika Amar Shaikh’s memoir about her tumultuous relationship with him, and the subjugation he put her through.

Mallika recounts meeting Dhassal through her brother-in-law at 14 in her memoir ‘I Want to Destroy Myself‘. The book is a painful description of her relationship not only with Dhassal, the person but also with Dhassal, the politician. She describes a different side to Dhassal: He was sometimes loveable, many times abusive, and on most occasions insensitive to her needs as a person, a partner, and a woman.

Also read: Book Review: I Want To Destroy Myself By Malika Amar Shaikh

He physically abuses her, passes on a venereal disease which he acquires in one of his visits to the sex worker in Kamathipura, rapes her before they get married, and eventually separates their son from her in a fit of anger for many months. She recalls Namdeo being a completely absent partner and eventually an absent father too. Both of them go through an endless, vicious cycle of drinking, fighting, abusing, and beating in front of the child.

She narrates their agonizing disagreements on parenting decisions which expose Namdeo’s ideological hypocrisy at home. Having grown up in a communist environment, she is certain on how she wants to raise her child- without religion, caste, and rejecting rituals like the naming ceremony. On the other hand, even though he claims to be Dhassal comes across as someone who is tokenistic in his parenting and is not sure of his philosophy. He wants to give the child a revolutionary name like George Jackson and refuses to celebrate his birthday. Ironically, he falls prey to his friend’s suggestion of idol worship of the Buddha statue that they decide to install on the eve of his child’s birthday.

Mallika exposes Dhassal’s hypocrisy in his politics as well. As a politician, he was brash, thoughtless, and larger than life. She believes that the internal conflicts took place because the Panthers lacked discipline.

Mallika exposes Dhassal’s hypocrisy in his politics as well. As a politician, he was brash, thoughtless, and larger than life. She believes that the internal conflicts took place because the Panthers lacked discipline. Dhassal does not contribute to household expenses claiming rising party costs but continues to live a lavish lifestyle himself; spends obscene amounts of money on party workers including their trips to Kamathipura. He also forces her to sell her jewellery when he can’t meet these expenses. There is a very poignant description of how she eventually sells the Soviet Land magazines in their house just so that she can feed the family.

According to her, the Panthers were just a bunch of young, directionless men who were trying to be scooped up by all political parties from the left to the center to the extreme right because of their non-commitment towards a particular ideology. All this takes place against the background of the Emergency in India—which Dhassal openly supported—which many believe was so that the government in power would drop the cases against him and his party for all the militancy and violence they allegedly indulged in. She is also vocal with him about his various political decisions. At one point, he decides to support the Shiv Sena which she opposes. “What do you understand of it?” he dismisses her.

Throughout the book, she talks of the irony of the way her husband was revered by countless people as the saviour of the oppressed while he continued to oppress the women in his life and outside. His hypocrisy is loud and brash like him in every incident that she recounts, except that he is deaf and blind to it. She feels trapped as most women in bad marriages feel. Eventually, she tries multiple attempts at dying by suicide.

Reading about Dhassal’s early life of abject poverty and social persecution was truly inspiring. Reading his poetry and about his politics makes one marvel at the man’s expressiveness, courage, intellect, and elocution. However, reading his wife’s memoir put me in an existential quagmire and made me confront many uncomfortable questions such as: Should Dhassal be kept on a pedestal as the ideal of hope and change for the oppressed when he was an oppressor in various aspects of his personal life? His benevolent narcissism makes it extremely difficult to objectively assess his oppression as opposed to his activism and social altruism.

Also read: The Contribution Of Dalit Women Shahir In Maharashtra’s Anti-Caste Movement

This cognitive dissonance that he and many powerful men like him exhibit between their public and personal lives also leads to another dilemma: What are the implications of the fracture between his public and private values on the issues of gender in the anti-caste movement?

We must keep in mind that Dhassal’s activism and politics did not exist in a social and political void but were part of a larger system of patriarchy. The most difficult question for me to answer was: Why am I critiquing Dhassal now? To give a voice to the voiceless- his wife, his mother, women around him at the receiving end of his oppression and the women who are part of this system where men like Dhassal are revered for their fight against injustice while inflicting another kind of oppression in their own homes. And finally, one is forced to confront the eternal question: Must one separate the art from the artist?

Like Chinua Achebe said, “An artist is committed to art which is committed to people“, Dhassal was no doubt committed to his art, politics, activism and to the masses; only that he did not extend that commitment to all people around him.

Nupur holds a Masters in Psychology and has been an educator for eight years. She is passionate about writing and loves incorporating writing as a medium in teaching. She is currently pursuing a Masters in International Human Rights from the Indian Institute of Human Rights, Delhi.When she is not teaching or writing, she loves reading, cooking and long distance running. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

Featured Image Source: Namdeo Dhasal, Facebook