Politicians have loudspeakers.

Himalaya Me Mahatma Gandhi ke Sipahi, Sundarlal Bahuguna, by KS Valdiya (2017)

But who will speak for the tree that will be cut?

Who will come forward for the dying river?

Who will protect the mountains?

It is now time to hear the voice of the tree being cut, the voice of the river, the scream of the mountain that is sliding.

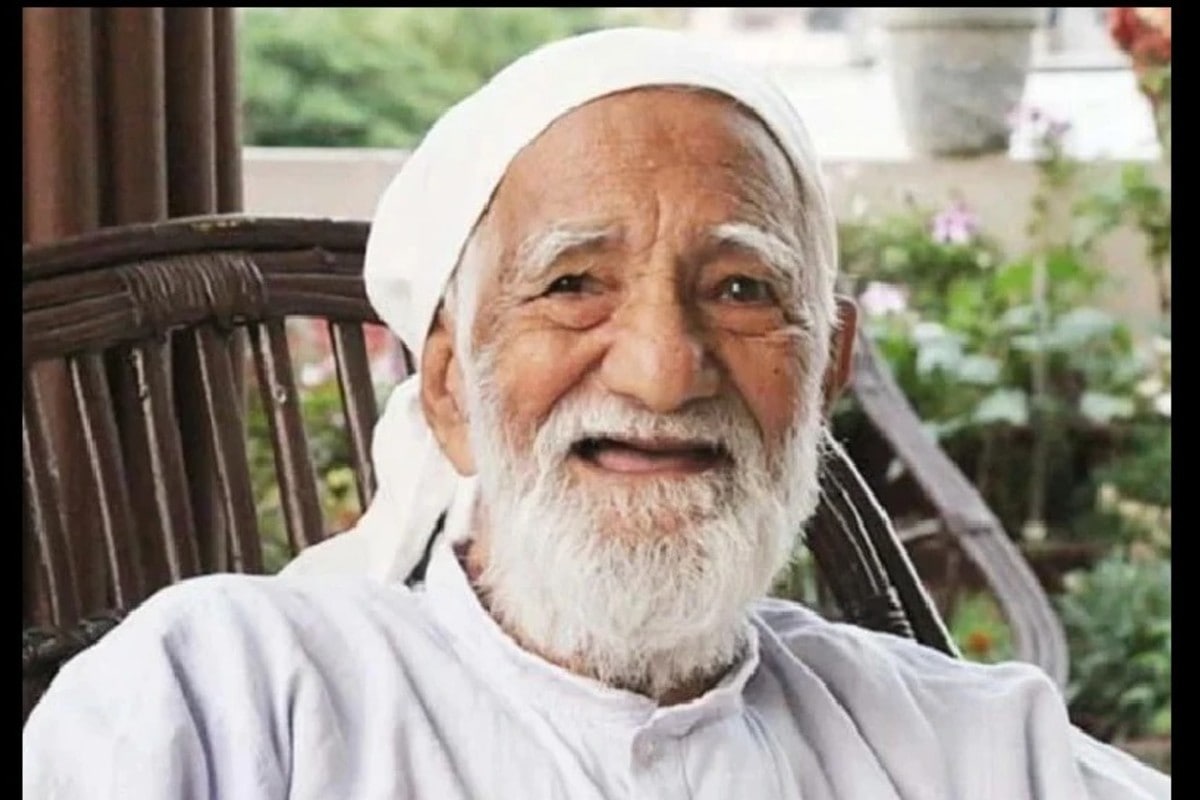

A lanky man with a thin face, kind eyes, disarming smile, white flowing beard and the most simple of attires turned the world upside down when he made people pause and notice an erstwhile oblivious but ecologically sensitive region – the Himalayas. It was perhaps also this saintliness, articulated in attire and thought, that gave Sunderlal Bahuguna a spiritual and cultural currency that no environmentalist perhaps has been able to replicate or command. Bahuguna is known predominantly for his environmental activism; which was just one facet of his illustrious life. From his adolescence to his old age, Bahuguna lived his life by Gandhian principles, at the core of which was practice that preceded preaching.

Freedom struggle to social work: Bahuguna’s journey towards environmental activism

Sunderlal Bahuguna was born in Maroda, near Tehri, Uttarakhand, on January 9, 1927. He was one of India’s pioneer environment activists. Ecofeminist and environmentalist Vandana Shiva noted that Bahuguna was inspired by Sri Dev Suman, who worked with Vinoba Bhave and Mahathma Gandhi’s disciples Mira Behn and Sarla Behn. While Suman became an inspiration for Bahuguna’s contributions to the freedom movement, the others prompted him to his foray into social activism.

Sunderlal Bahuguna was a staunch Gandhian and humanitarian. For him, nature was sacred and all natural entities worth worshipping, for nature is the ultimate provider. Bahuguna’s idea of nature also had a feminine characteristic to it. Perhaps then, it’s no wonder that women were cornerstones of Bahuguna’s many movements

Bahuguna joined the freedom movement at age 13 in the Tehri region and was threatened with imprisonment for his participation and for sending out news related to Suman in clandestine. He somehow managed to escape to Lahore only to return and face arrest at the peak of the freedom movement in the erstwhile Tehri Kingdom. After the merger of the Tehri state into the Indian union in 1949, Bahuguna became the secretary of Tehri Congress.

Bharat Dogra, Sunderlal and Vimla’s biographer narrated the story of the couple’s atypical marriage agreement. Vimla, a social activist in her own right and disciple of Sarla Behn, married 29-year-old Sunderlal on one condition- that he should leave politics and they would pursue social work by serving people in rural areas and rugged terrains. Bahuguna agreed, and post marriage, the couple settled and served in Silyara, near Ghanshali, close to the Balganga river. Their marriage was not just a partnership in life but also a commitment to social activism for fifty-odd years.

In 1981, he was nominated for the Padma Shri by the Government of India (GOI) but he refused the award in order to register his protest against the Tehri Dam Project. He went on to receive many more accolades and honours later. In 1986, he received the Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Constructive Work. In 1987, he received the Right Livelihood Award. In 2009, he was awarded the Padma Vibhushan (the second-highest civilian award) by GOI. In 1989, IIT Roorkee conferred on him an honorary doctorate degree in Social Sciences.

Following the failed Tehri Dam Protest, Bahuguna moved to Dehradun in 2004. After a hiatus of 3 years, he started a protest against the proposed USD 250 million International Himalayan Ski Village, near Manali; a project undertaken by American tycoon Alfred Brush Ford. Bahuguna’s reaction to it was that the people initiate “a long-term battle to stop global economic giants from squeezing the Himalayan natural resources.” Apart from his continued support to environment related movements in India, even after the onset of frailty and old age, Bahuguna continued to engage audiences via interviews, lectures and writings. Some of his books include Dharti ki Pukar, The Road To Survival and Environment Crisis and Sustainable development.

Years of activism and fasting caught up with Bahuguna. Covid-19 and associated pneumonia led to his demise on May 21, 2021, at the age of 94. He is survived by his wife Vimla and three children, Madhuri, Rajiv and Pradeep.

Also read: Saalumarada Thimmakka: Padma Shri Award Winner And An Environmentalist

An undisputed icon across the political spectrum

Sunderlal Bahuguna was a staunch Gandhian and humanitarian. For him, nature was sacred and all natural entities worth worshipping, for nature is the ultimate provider. Bahuguna’s idea of nature also had a feminine characteristic to it. Perhaps then, it’s no wonder that women were cornerstones of Bahuguna’s many movements. David L. Haberman noted that Bahuguna’s activism conjoined ecological sciences, insights from Indian religious traditions, and Gandhian non-violence.

Sunderlal’s life and activism became a legacy for youngsters who saw the Chipko Movement first hand and for contemporary youth activists, who in Bahuguna, find a mentor and idol of value despite the temporal and spatial gaps in their respective politics

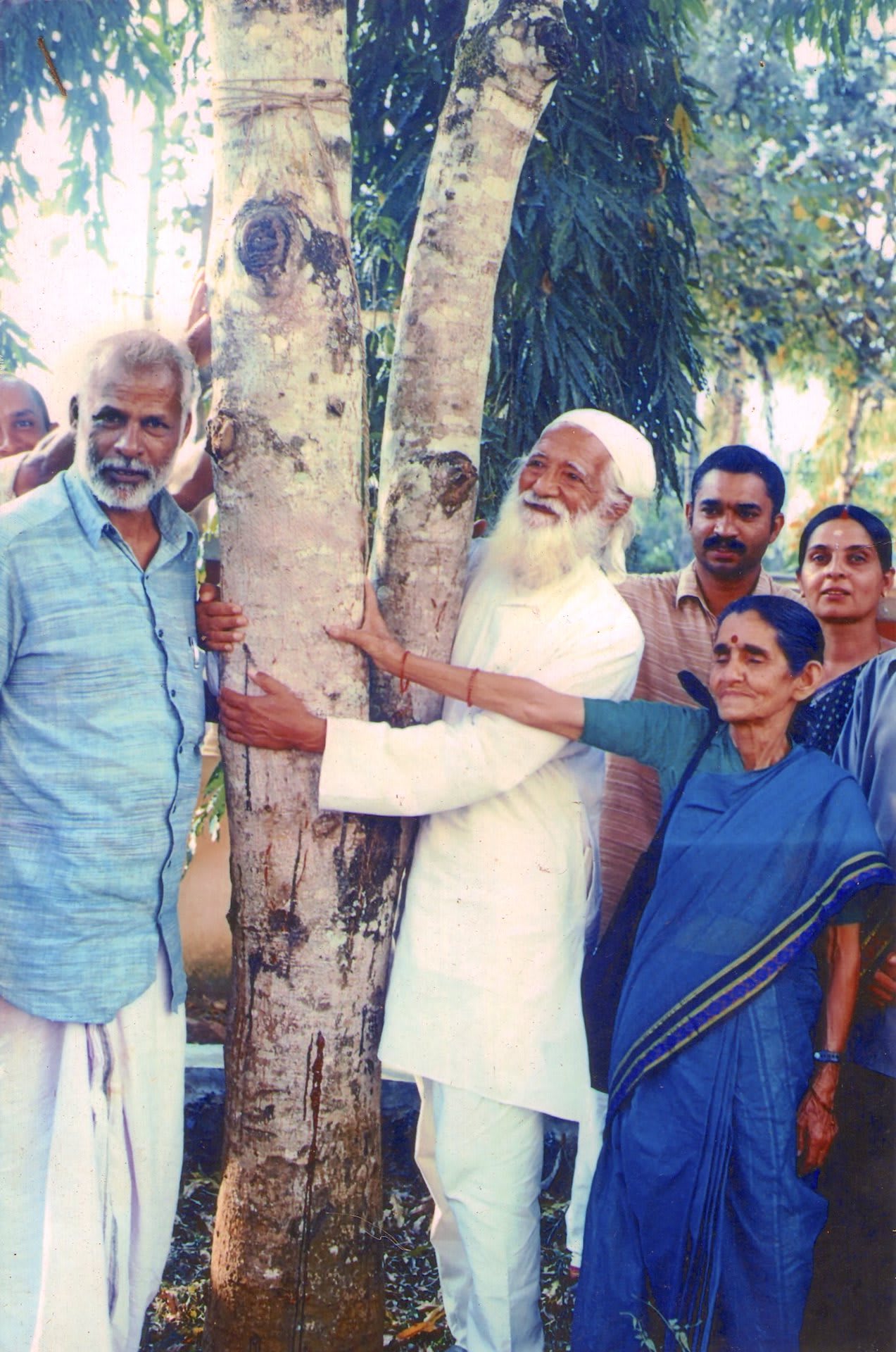

In the 1970s, Bahuguna made his first foray into mass movements with the Chipko Movement. The movement was started by Gaura Devi and 28 other women in a village, inspired by Chandi Prasad Bhatt, and entailed the hugging of trees to prevent their felling by approaching contractors. Sunderlal Bahuguna’s merit lay in two things – articulating the movement to the masses in and beyond the Himalayas, and, shaping the movement into a mass movement without appropriating it. At all times, the activity remained decentralized, and women were in roles of leadership and mobilization. For Bahguna, Chipko was both an environmental and labour movement.

The campaign to save Himalayan forests culminated with a ban on commercial felling above 30 degrees slope and above 1,000 mean sea level in 1981. He undertook a precarious 4000 Km padayatra from Kashmir to Kohima (it was also a transnational walk) to bring further attention to the entire Himalayan region.

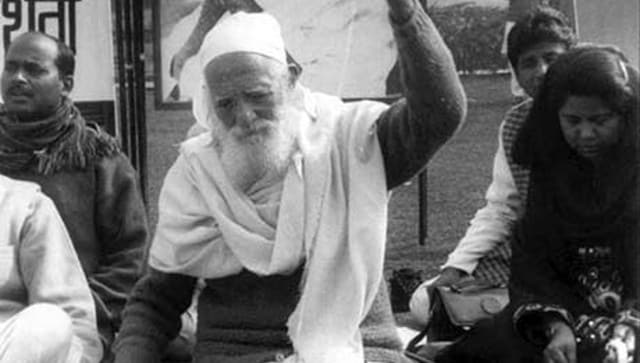

In the 1980s, Bahuguna was to be associated with the Tehri Dam Movement. He protested India’s most extensive dam construction, for he understood that mega hydel-power projects in a seismic zone present a looming threat to people and resources. Inspite of one of the most prolonged fast in Independent India of 56 days, Sunderlal’s efforts went futile, and the government went ahead with the project. Haberman, who interviewed him in 2000, recalled how “personal was political” was to the activist. Bahuguna, who saw the Ganges as his mother, shaved his head and performed death rituals for Mother Ganges once the gates of Tehri were closed towards the end of 2001. His protest continued till 2004. Even though Bahuguna could not save the Ganges, his failed protest still serves political value in its ability to inspire activists and generate awareness about massive dam projects amongst the masses.

Jagdish Krishnaswamy, prominent environmental scientist noted that Bahuguna’s background was deeply seated in traditional and cultural ethos – thereby allowing him to have an audience across the political spectrum. He adds that in India, where environmentalism is often to the left of centre, Bahuguna’s pan-spectrum appeal perhaps confounded many activists resulting in allegations and critiques of his Tehri Dam Movement as Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) and other right-wing groups joined the movement for different ideological ends. For Krishnaswamy, these are baseless, “to have an impact, one sometimes needs icons and leaders who command respect across the political spectrum— Bahuguna was one of those figures.”

His environmentalism went hand in hand with his worldview of integrative social development. Sunderlal and Vimla undertook various anti-caste movements, worked towards Dalit empowerment and helped women mobilise against the liquor mafia in the hills. They also, among other environmental actions, were part of the Beej Bachao Andolan.

An evergreen legacy of eco-centric living

Sunderlal’s life and activism became a legacy for youngsters who saw the Chipko Movement first hand and for contemporary youth activists, who in Bahuguna, find a mentor and idol of value despite the temporal and spatial gaps in their respective politics.

Rajendra Singh, a Water Conservationist from Alwar, Rajasthan, reminiscing his first meet with Bahuguna and its impact on his life, said, “When I met him for the first time in 1975, it was an awe-inspiring moment. I was a student and greatly moved by his thoughts and ideas. Harmony with nature is the only way of life, he believed and instilled in many young minds an environmental consciousness at a time when the world was blinded by a mad race of unprincipled development.”

Vandana Shiva, in her remembrance of Bahuguna, said, “Sunderlal Bahuguna and his wife Vimla are my teachers in Gandhian philosophy, which tells you that ecology is a permanent economy, and that simple living in service of others is central to making a shift from egocentric thinking and living to eco-centric thinking and living.” She says that the three Gandhian principles that she learnt from the Bahuguna couple are – Swaraj: self-rule and self-organization, Swadeshi: self-reliance, local economy, and, Satyagraha: the force of truth and the obligation to not cooperate with unjust brute law.

Ann, a Masters Student of Social Work and an environmental activist, on being asked what Sunderlal Bahuguna’s relevance to her activism is, said, “His legacy has personally taught me that any activism cannot be atomized and that the environment impacts us all and hence we all must stand for it together. Sunderlal Ji has also broadened the concept of environmental justice to take it beyond just conservation and preservation. Activists like him have paved the way for future generations to take up the responsibility of taking care of the environment in a more integrated manner too.”

Mohini, an environmental activist from Dehradun, Uttarakhand, who works for Project Paani said, “Undoubtedly, having activists like late Sunderlal Bahuguna Ji has indeed been inspiring to each and every person, especially those who hail from the hilly areas of Uttarakhand. The man was a legend, and his legacy will continue to inspire future generations as well. While it is true that he came from a different era, Sunderlal Jii’s values and thought process is just as valid now as it was then.”

But it’s not just individuals who have imbibed his values and were inspired by him. In the Western Ghats region, an important inspiration for the great Appiko movement for saving trees of the Kalse forests in Karnataka came from Sunderlal Bahuguna’s Chipko Model.

On his deathbed, Bahuguna is reported to have asked that people not mourn him but carry on his efforts to save the Himalayas.

Bahuguna, who grew up in the Himalayas, connected the dots of ecological destruction well. He wrote that deforestation led to soil erosion, thereby pushing the men out of villages to seek jobs in cities. This left women to “bear all the responsibilities of collecting fodder, firewood and water, apart from farming.” When Bahuguna said, “Ecology is permanent economy,” he did not take an anti-development stance but instead took a pro-development view where growth was replaced by diffused, sustainable and integrated development. As the country charts its growth stories, it’s necessary to not err on the side of caution – hydel power projects in the Himalayas, may give the growth story the push it needs at the moment, but it may also come back to unfurl tremendous damage if not steered carefully.

We may chart our own politics, but any attempts at restoring ecological sanity which encompasses a development approach sensitive to the dynamism of climate change and rooted in the ethos of indigenous cultural practices, will always prod us to look back at the life and times of late Sunderlal Bahuguna.

Also read: Here Are 5 Recent Environmental Movements You Need To Know

Featured Image Source: News18

About the author(s)

Harshita is a postgraduate student at the University of Delhi. She is interested in areas of Gender, History and Social History. Her research interests are at the intersection of gender, power and social categorisations.