Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for September, 2021 is Parenthood. We invite submissions on the many layers of being parents, having parents and navigating the social norms of parenting throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

Societal standards have time and again defined motherhood and what it is to be a “good” mother. The burden of creating a nurturing, sheltered environment for kids has primarily been put on mothers and this is where the concept of being a ‘perfect‘ mother originates from.

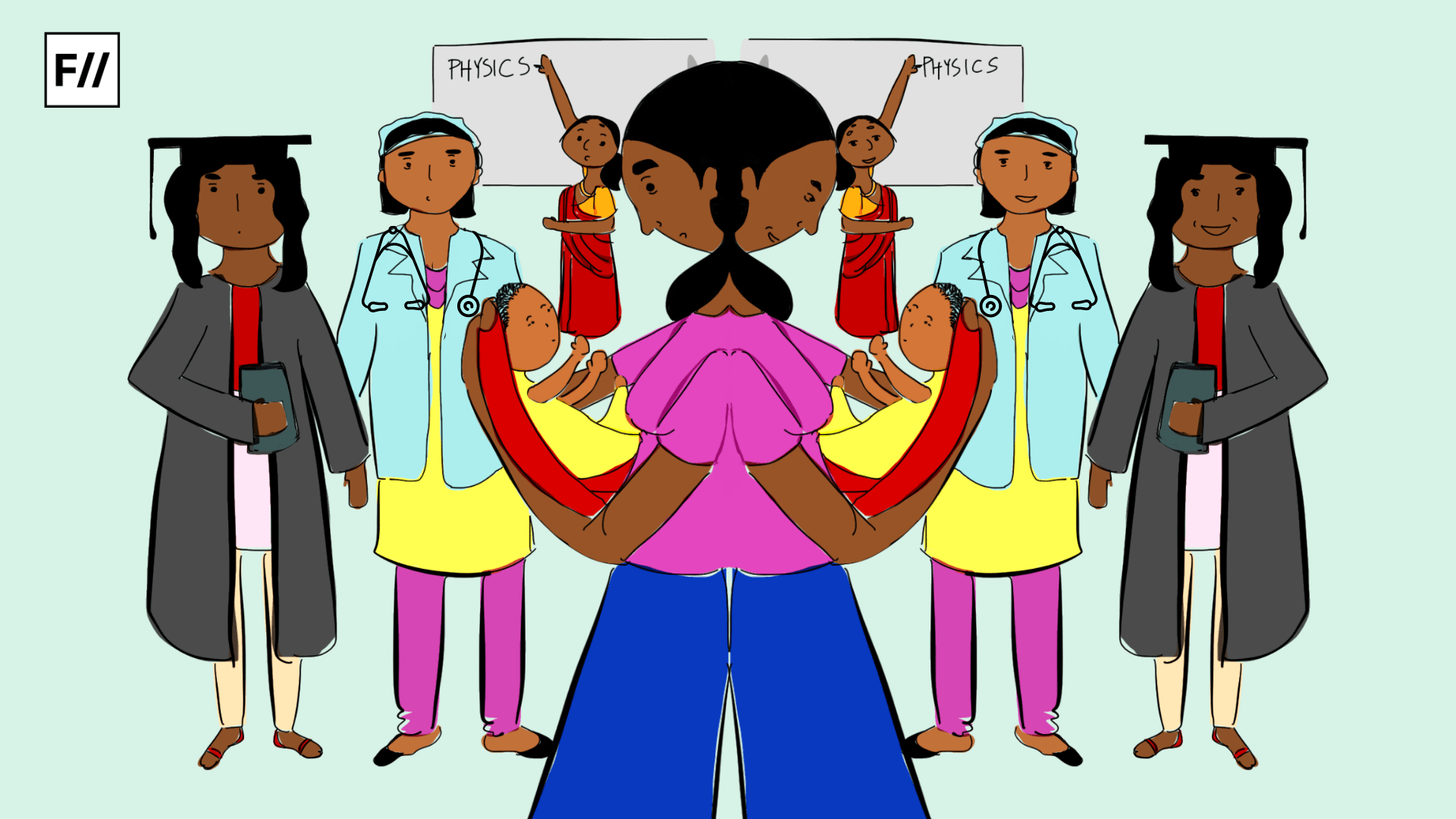

This has cemented the long-established assumption that women are born with ‘maternal instincts‘, to nurture and care for others where the pressure, sacrifices and struggles to live up to these ‘natural instincts’ are brushed under the carpet. As a consequence, this has solidified another popular belief that as women are naturally more nurturing, they are passive and less ambitious compared to men.

This expectation does not only remain within the domestic space or responsibilities. It reflects in the way women are perceived in all walks of life. Such gender differences and constructs of motherhood have affected women’s place in society along with the stereotyping of the act of ‘mothering‘ itself.

Motherhood is such a powerful place. It sure has tremendous potential to shape an individual’s life. Unfortunately, it has been positioned as part of patriarchy, as a means to exploit and victimise women and their labour. For decades, devoting one’s life solely to play a role as a mother and be bound by its duties has been normalised.

As ‘good mothers’ don’t have a life that does not involve primarily worrying about their child’s requirements, the course and progression of motherhood are often set to an insane benchmark of care and perfection, regardless of marital or employment status.

We need to stop forcing career ending decisions, sacrifices, and gender norms on women under the label of motherhood. We all have heard countless stories from older generations of women about the abuse and sacrifices endured in the course of motherhood. Such stories are unfortunately glorified and seen as ‘success stories‘.

Popular culture and media representations of idealised ‘mothering‘ further add to this problematic mix by defining and shaping the identities of “good” and “bad” mothers. This not only ignores the intersectionalities of class and caste, but also thrives as business models that make million-dollar profits by marketing these stereotypes of mothering. Achieving the perfect standard of motherhood also then becomes intertwined with consumerism

Over the years, many researchers have debated over the effect of maternal deprivation on a child’s growth, and if someone grows up without a mother figure, whether they would become ‘affectionless‘ individuals as is popularly believed. The positioning of the stay at home mother as a selfless presence with no personal boundaries has ignored the cultural and economic contexts leading to the destruction of the opportunities for stay-at-home mothers in the social and political space.

The idea of being a mother should not be about feeling stuck. One must be able to live a life of their own and be able to take care of their own needs without constantly feeling guilty about it. The concept of being restricted to space and devoting all the time and energy to fulfilling household and child care responsibilities to the point where the sense of self and identity gets blurred, is horrifying and beyond justifiable.

Also read: Paternity Leave And Parenting Stereotypes: Policy Changes Must Be Backed By Change In Attitude

Popular culture and media representations of idealised ‘mothering‘ further add to this problematic mix by defining and shaping the identities of “good” and “bad” mothers. This not only ignores the intersectionalities of class and caste, but also thrives as business models that make million-dollar profits by marketing these stereotypes of mothering. Achieving the perfect standard of motherhood also then becomes intertwined with consumerism.

There’s an immediate need to stop manipulating and emotionally guilt-tripping mothers into solely dedicating the prime years for their lives in trying to achieve the culturally and ethically set unrealistic standards of motherhood. This kind of self-sacrifice is not love. It’s a lack of self-love which results in years of self-sabotaging.

The idea that childbearing and childrearing should be prioritised over any and everything else, including one’s own needs, is abuse. The weight of responsibility of being a caretaker shouldn’t feel like a burden which later results in feelings of entrapment and suffocation. Every individual deserves to choose themselves first, to have respect and be whatever/whoever/however they want to be.

We need to shift from the traditional understanding of ‘mothering‘, which has deliberately stereotyped mothers into all forgiving, ever present caregivers, thereby diminishing the role of the father and other family members, workplaces and the state in childcare and nurture. Ironically, despite the fact that mothering as a concept and mothers as a socio-cultural group are pedestalised and deified, in practice, mothering itself remains both culturally and politically gendered and undervalued

As long as societies have existed, women’s reproductive abilities have always given more importance than their productive abilities, which has resulted in a common misconception that all women are born to be mothers. Choosing to give birth is a privilege that includes having the resources and access to safe pregnancy and being in a healthy relationship. Not many women get to experience this.

Many times, motherhood is imposed; be it by an unwanted pregnancy, sexual abuse, teenage pregnancy, forced marriage, social pressure, and so on. Often, in the research on motherhood and its struggles, the intersection of class, caste, sexual orientation, and race, has been neglected. These intersections are the foundational bases of our social structure which deal with power dynamics and they cannot go unaddressed because mothers are critically affected by social, political, and economic structures.

As culture and public sector incentives have always been interlinked, it influences the formation of family policies and their execution. Such policies are majorly dependent on the social and cultural expectations of the role of women as mothers. Additionally, it affects the choices and options that women have as individuals and as mothers to create space for themselves.

Due to the lack of accessibility and availability of inclusive, gender sensitive policies that ensure equal, paid opportunities and health care programs for parents, especially mothers, families are left with no choice but to resort to the ‘one breadwinner’ model where usually women take up the caregiving needs.

We desperately need policymakers to invest in family-oriented schemes, maternity leaves, and affordable child care programs. These policies would enable us to destroy the systemic barriers to women’s equality and ultimately boost productivity and economic growth by increasing women’s, especially mothers’ participation in professional engagement after childbirth.

Also read: ‘Shakuntala Devi’ And The Patriarchal Trope Of The ‘Good Mother’

The glorification of the ‘multitasking supermom‘ trope must be called out as it is counterproductive. Mothers are now expected to have professional careers while performing the traditional caregiving needs with the same total absorption. This has only reaffirmed women’s role as primary caregivers.

Ultimately, it results in the under-representation of women in positions of power and authority. If we are trying to reinvent the roles of women in public and private spaces and promote powerful family virtues, then there should be equal distribution of responsibilities among genders. There should be work environments where employees (both male and female) shouldn’t be torn between work and family obligations, and genuinely supportive policies by organisations.

Women should not be pushed to decide their self worth based on the roles they play at home. We, as a society, need to start normalising mothers trying to rediscover themselves and take up more space. While motherhood is a place of joy and thrill for many, the structures defining it, have separated the roles for both, men and women.

We need to shift from the traditional understanding of ‘mothering‘, which has deliberately stereotyped mothers into all forgiving, ever present caregivers, thereby diminishing the role of the father and other family members, workplaces and the state in childcare and nurture. Ironically, despite the fact that mothering as a concept and mothers as a socio-cultural group are pedestalised and deified, in practice, mothering itself remains both culturally and politically gendered and undervalued.

References:

1. Cole, E. R., Jayaratne, T. E., Cecchi, L. A., Feldbaum, M., & Petty, E. M. (2007). Vive la difference? Genetic explanations for perceived gender differences in nurturance. Sex Roles, 57(3–4), 211–222.Bowlby, J. (1996/1953)

2. Child care and the growth of love. London: Penguin Books

3. Damaske, S. (2013). Work, family, and accounts of mothers’ lives using discourse to navigate intensive mothering ideals. Sociology Compass, 7(6), 436–444

4. McClellan, E. (2007). The mass media and its depiction of mothers. Retrieved 4 July 2012

Samruddhi is currently a law student who is primarily interested in gender studies and psychology. In her free time, you would either find her napping, obsessing over dosa or making a cup of chai for herself. She may be found on Instagram

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India