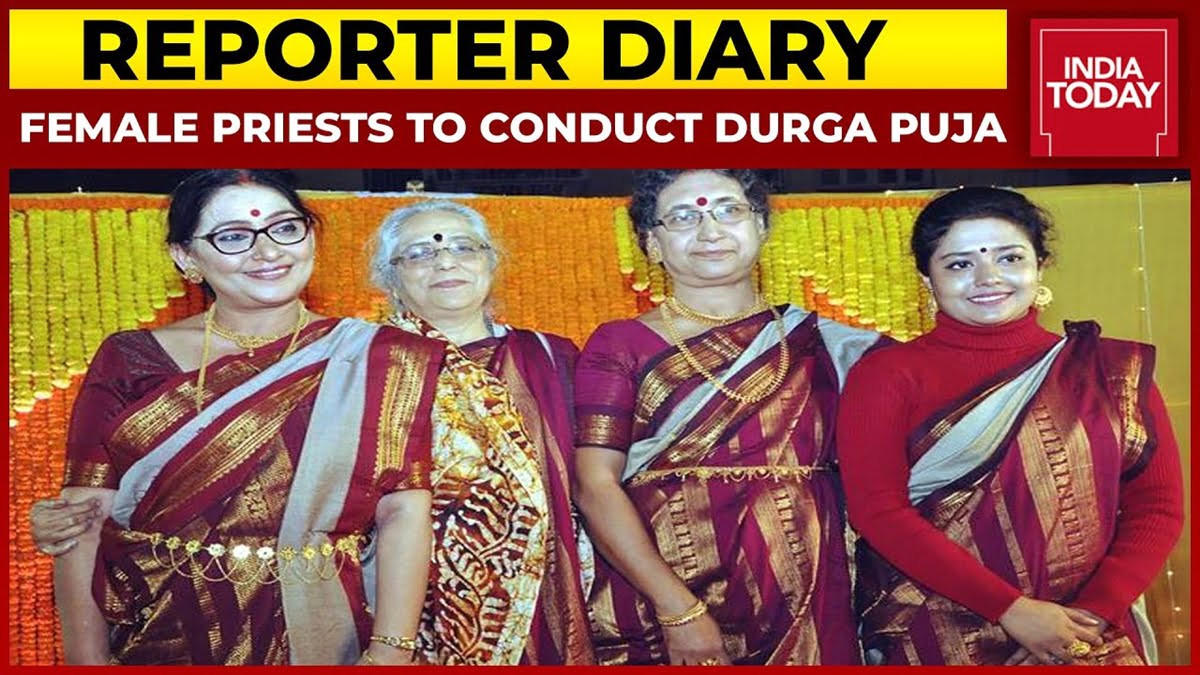

Recently, a video of four female priests performing the rituals at a Durga Puja Mandap in Kolkata surfaced on different social media platforms. The video shows four Brahmin female priests conducting the rituals at a famous Durga Puja pandal in South Kolkata. As much as I was elated to see the female priests breaking conventional gender barriers, I noticed that there was one thing that remained completely out of the conversations that was taking place surrounding it. I saw many articles about it online – praising, supporting and glorifying the gesture of the Puja committee, but none of them seems to address the one thing intricately linked with priesthood, that is, one’s caste identity – let alone challenge it.

One way of understanding the caste system is through occupational segregation or division of labour. It consists of four varnas – the upper-caste Brahmins (priests and teachers), the Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaishya (traders, retailers, and money lenders), and the Shudra (servants and manual labour). The people of Scheduled Castes or the Dalits were relegated and subordinated to menial forms of employment because of their caste identity.

Such a system structures labour and occupational choices in a hierarchy that allows one group to engage in particular activities while at the same time precluding others from the same choices because of their position in the caste ladder. There is no doubt that caste has immense implications in shaping life outcomes and often becomes the salient identity when related to such occupations. Its existence neither can be silenced nor can be denied.

Also read: The Historical Erasure of India’s Groundbreaking Dalit Feminism

Which is why, a group of Brahmin women performing the rituals exclusively reserved for Brahmin men does not challenge the overarching oppressive systems instead, their participation only permeates its existence while consolidating the status quo. When I saw the video, I could not help but notice the attire of the women – the clothes they wore or the eloquence in her English speaking style. I could not help but see the privileges that she embodied and reproduced in those spaces. Letting a Brahmin woman conduct the rituals doesn’t do much to resist, challenge or dismantle broader systems of oppression. It distorts the social reality just enough in order to continue to maintain an upper-caste Brahminical hegemony. It may also result in co-opting feminist movements by realigning them with upper-caste interest, as have been the case historically.

The decision albeit challenged labour-gender dynamics and may have some symbolic significance but failed to acknowledge the caste affiliation associated with priesthood. Instead, it perpetuated caste-based practices covertly under the garb of gender equality. The underlying notions of casteism, therefore, remains unrecognised and in the process, invisibilised by asserting a narrative of feminism and gender equality. The rhetoric sets itself in a way where caste questions are diverted and subsumed under the bigger goal of abolishing patriarchy.

However, it is not about undermining the gesture by the Puja committee, but there are a few questions that need careful deliberation – Can a system like patriarchy be understood independent of other factors that influence and determines its course of action? Can we capture the nuances and intricacies that shape gender experiences without confronting all the other systems of social stratification and hierarchies?

There are a few questions that need careful deliberation – Can a system like patriarchy be understood independent of other factors that influence and determines its course of action? Can we capture the nuances and intricacies that shape gender experiences without confronting all the other systems of social stratification and hierarchies?

Of course, there is a vast literature on intersectionality that precisely argues and points to the existence of multiple identities that intersect and overlap, thus simultaneously shaping experiences of discrimination and exclusion and determining life chances and outcomes. Understanding gender dynamics without factoring in the other aspects will end up providing a narrow perspective, thus dismissing the complexity of the issue. Caste identity in priesthood cannot be escaped or remain unquestioned. Any attempt to subvert it, will only result in strengthening upper-caste power and privileges.

Also read: Durga Puja And The Myth Of Worshipping “Nari Shakti”

Like mentioned before, the objective of this piece is not to denigrate the Puja Committee but to bring the issue of caste into the broader discourse and to facilitate further dialogue regarding the matter. The caste system is very much a part of our reality, even though its way of operating and reproducing has changed. It may not be as explicit as it was before. Challenging systems of power needs an intersectional approach and, unless we start looking at certain things from that perspective, we may be complicit in reproducing a social structure that privileges particular individuals while simultaneously depriving and excluding others.

Without acknowledging the caste dynamics inherent in priesthood alongside gender, it will only end up reinforcing upper-caste identities. Perhaps, representation of women from the disadvantaged caste groups in such occupations can facilitate breaking down the Brahmanical social order or realistically, initiate a change in a direction that is inclusive and democratic.

Moubani Maitra is a MA student at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, Netherlands. Her research looks at the intersection of politics and policy – more precisely, how contemporary politics shape social policies in India. You can find her on Linkedin, Instagram and Facebook.

Featured image source: YouTube

Excellent article!

Your article is right on spot. I say this as a fully self aware privileged woman. Their attire, visuals seem more like optics than anything else. In fact this women seem more privileged than the male brahmin priests we see throughout the temples in small towns and villages.

While it’s more power to them, I don’t see how this can be any ground breaking feat at all. Reading from a printed paper doesn’t make a priest. The priests study Sanskrit, practice vedas, practice rituals for years and work as apprentice before becoming main priests. The wages for this priests is not very high either and they are at the mercy of temple trustees.

Their attire is simple cotton dhotis and angavastras that show servitude nature of their duties to the deity they serve.

The women who proclaim themselves as priests are decked in silk sarees and jewelry to rival the goddess in the temple herself.

It feels more like a Sunday gathering of women to chant shlokas giving them a chance to wear their fine attires