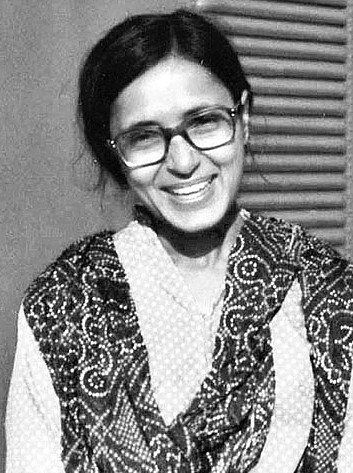

Perhaps no account of the Indian feminist movement can be accurately explored without the mention of the revolutionary leader Anuradha Ghandy. From being a part of the Dalit Panther movement, the Naxalite movement, to expanding the now banned Krantikari Adivasi Mahila Sanghatan, Ghandy worked with and for oppressed communities everywhere. In addition to her ground work, Anuradha Ghandy also wrote extensively on issues of women, caste, and fascism. ‘Philosophical Trends in the Feminist Movement’, ‘Caste Question in India’, and ‘Fascism, Fundamentalism and Patriarchy’ remain her most important works. Her analysis, much of it derived from her ground experiences, enriches our understanding of these subjects monumentally.

On Hindutva

Written around the appointment of Narendra Modi as the Chief Minister of Gujarat in 2001, Anuradha Ghandy provides an excellent foresight to the rise and spread of fascism and Hindutva in Fascism, Fundamentalism and Patriarchy. She begins by highlighting how the ideology of Hindutva diverts people’s attention from their mass destitution and onto imagined enemies.

Written around the appointment of Narendra Modi as the Chief Minister of Gujarat in 2001, Anuradha Ghandy provides an excellent foresight to the rise and spread of fascism and Hindutva in Fascism, Fundamentalism and Patriarchy. She begins by highlighting how the ideology of Hindutva diverts people’s attention from their mass destitution and onto imagined enemies.

She then goes on to explain the complicated relationship between fascism, fuelled by religious fundamentalism, and patriarchy. Religious fundamentalism, she says, tries to evoke a nostalgic reimagination of history where all was well. It then blames contemporary modern culture for the distortion of that peace and tries to mobilise people to return to traditional values. These traditional values require the submission of the woman to the household, stripped of all rights and personal autonomy. “It is clear that at present the foremost enemy of women are the Hindutva forces,” she writes. In the Indian context, fascism is so intrinsically married to the caste and feudal order, it requires its absolute continuation in order to sustain itself.

She also outlines Hindutva’s promotion of Sati in cases such as Roop Kunwar’s forced immolation in 1987 and its usage of rape as a weapon of political onslaught like the kind seen during the Gujarat riots. “They are using women to pursue their political ends, both when they are mobilising them and when they are sexually attacking minority women. It is important to remember that these Hindutva forces, whether they be of the Sangh Parivar – the RSS, the Bajrang Dal, the BJP – or whether they are within other political formations like the Congress, they share the same reactionary attitude to women,” she writes. She also mentions the attitude of the Indian state towards minorities and women and describes it as patriarchal, feudal and Brahmanical in its core essence.

Anuradha Ghandy’s analysis of the women sects of the RSS is also very enlightening. The RSS ideology deems the woman an important part of the family but her public participation is denied. The woman essentially is tasked with the promotion of Hindutva ideology in her household and neighbourhood. She is charged with the responsibility of raising her children, child bearing being one of her most important duties, in accordance with the ideology of Hindutva. Her survey of RSS and Hindutva’s relationship with women’s right is extremely relevant today and an important read for all feminists fighting the twin forces of patriarchy and Hindutva. “For revolutionary and democratic forces, for the progressive women’s movement, the tasks are clearly laid out: To fight the rise of the Hindutva fascist forces in India it is not sufficient to fight it only in the political realm, but to fight it on all fronts,” she concludes.

Also read: Dalit Panthers: A Radical Resistance

On Feminism

Anuradha Ghandy’s understanding of feminism in its various facets is exemplified in her work Philosophical Trends in the Feminist Movement. It is an extensive survey and consequent critique of the main schools of thought of feminism including the liberal school, the postmodern school, the socialist school, the radical school and the anarchist school. Ghandy recognises the importance of theory-building in feminism and its close relationship with groundwork and movement building. She blames the failure of radical feminist and socialist feminist movements on the improper and under-researched theory building: “how incorrect theoretical analysis and wrong strategies can affect a movement can be clearly seen in the case of the feminist movement. Not understanding women’s oppression as linked to the wider exploitative socio-economic and political structure, to imperialism, they have sought solutions within the imperialist system itself.” She connects class struggle, and the imperialist world system to women’s movements everywhere and concludes that divorcing either of these from feminism will prove to be counterproductive.

Ghandy firmly believes that women’s liberation needs to direct its attention to the working class and peasant class women, and her report ‘The Revolutionary Women’s Movement in India’ highlights the same. She outlines in detail the work being done in rural areas of Andhra Pradesh and the mobilisation of peasant women. Furthermore ‘Changes in Rape Laws: How far will they help?’ calls attention to the usage of rape as a political weapon.

On Caste

Anuradha Ghandy was an instrumental part of the Dalit Panther Movement of 1974. Her understanding of the caste system of India is most famously exhibited in ‘Caste Question in India’ and ‘The Caste Question Returns’. She writes that caste has been the most important means of exploitation of labouring masses: “for the ruling classes in India, from the ancient to the modern period, the caste system served both as an ideology as well as a social system that enabled them to repress and exploit the majority of toilers.” In ‘Caste Question in India’, she traces the development of caste from ancient times to modern. She highlights how everyone who came to rule India adapted to this system very quickly and learned how to manipulate it to exploit the masses.

In ‘The Caste Question Returns’, she undertakes another important inquiry. She begins by sketching the relationship between the Left and the Dalit movements. She faults the dwindling alliance between these both to two main reasons: “Firstly, the traditional ‘communists’ (specifically the CPI and CPM) have not understood the caste question in India and have often taken a reactionary stand on the Dalit question. Secondly, the established leadership of the present-day dalit movement do not seek a total smashing of the caste system, but only certain concessions within the existing caste structure.”

Ghandy believed in the total abolition of caste. Democratisation in India, she writes, is not possible without ridding Indian society of the caste system. “Democratisation of society means primarily smashing these old feudal institutions – in economic relations, in the re-organisation of political (state) power and in social relations between man and man. Basically, the essence of the democratic struggle must be to build a truly independent India and a thorough revolutionization of all economic, political and social relations.” This piece also provides an insightful criticism of the communist stance on caste, which she called intellectually lazy, and ultimately calls for unity between the left and the anti-caste movements.

Also read: A Marxist-Feminist Reading Of Sexual Division of Labour In Family

Her insights are an important read for any feminist. And yet her name is spoken in hushes and her life’s work and writings remain confined to a few communist corners. Anuradha Ghandy was a communist, a revolutionary feminist, an educator, but the only identity that the Indian state ensured she be known by was a Maoist terrorist.

Anuradha Ghandy’s work takes account of multiple dimensions of society. Even though some of her writings deal with complicated subjects, they are written in simple language with the masses in mind. All of her work is available for free online. Her insights are an important read for any feminist. And yet her name is spoken in hushes and her life’s work and writings remain confined to a few communist corners. Anuradha Ghandy was a communist, a revolutionary feminist, an educator, but the only identity that the Indian state ensured she be known by was a Maoist terrorist.

It was while teaching a group of Adivasi women in the forests of Jharkhand, that Ghandy caught malaria and died in the April of 2008. In her foreword to Philosophical Trends in the Feminist Movement, Arundhati Roy perfectly encapsulates Ghandy’s spirit, “Anuradha Ghandy shows us a mind and an attitude that is unafraid of nuance, unafraid of engaging with dogma, unafraid of telling it like it is — to her comrades as well as to the system that she fought against all her life. What a woman she was.”

About the author(s)

Halima is a History graduate from Lady Shri Ram College for Women. She has worked with grassroots political parties as well as international organisations. Her research interests are feminist theory, foreign policy, and area studies. She is currently doing a Master's in International Relations. In her free time, she passionately advocates for Phineas and Ferb songs for Grammy's.