When educator Maniben Amin’s husband passed away when she was just 28, she refused to shave her hair, or don the shelu – the maroon-coloured saree traditionally worn by widows in Gujarat. Maniben’s decision to not dress like a widow earned her the wrath of her family, but she didn’t budge, says her granddaughter Professor Vibhuti Patel. On the occasion of #Women’sHistoryMonth, we bring you the lesser heard story of children’s educator Maniben Amin, a freedom fighter who was part of the women’s movement and who worked extensively on children’s education in Gujarat.

On the occasion of #Women’sHistoryMonth, we bring you the lesser heard story of children’s educator Maniben Amin, a freedom fighter who was part of the women’s movement and who worked extensively on children’s education in Gujarat.

Through mixed channels of video conferencing and telephonic conversations, Professor Patel narrated the story of her gently fierce maternal grandmother and their relationship to Feminism In India. “I was her favourite, I think, because I was dark skinned”, she reminisces. “I didn’t start formal schooling till Class III, and from the first year I would get bullied for my complexion. But Mani Ba (grandmother) supported me, and told me never to care about bullies, while practicing kindness towards everyone.”

Also read: Ahilyabai Holkar: The Brave Maratha Queen Who Championed Women’s Education And Empowerment

The Story of an Educator

Maniben Amin was born in 1911 in Baroda, when Saijirao Gaekwad’s progressive rule had been established in Gujarat. She got married at the young age of 14, and was widowed in 1939, at the age of 28. She was divested of most of her property by her relatives because she refused to follow conservative ideas of widowhood. She stood her ground and eventually went to Bombay to be an apprentice under Tarabai Modak, and Gijubai Badheka, who were among the pioneers of Montessori education in India. She trained to be a teacher under them. When she returned to Baroda in 1940, she transformed one of the bungalows in her colony to Shishu Kunj, a Montessori school. She used her newly learned skills of interactive education and fun learning as tools in Shishu Kunj, which earned her a great deal of popularity in Baroda.

Soon after Shishu Kunj was first founded, Alembic Chemical, a conglomerate founded in 1907 by B. D. Amin, Professors T. K. Gajjar and A. S. Kotibhasker, took over its functioning and started adding a new grade every year to it. Established in 1940, Shishu Kunj was renamed the Alembic High School and became a full-fledged high school in 1960. Maniben was offered the position of school headmistress, but she’d declined the offer. She wanted to continue as a teacher. So devoted was she to her life as a kindergarten teacher that she started individually tutoring children with learning difficulties. She would begin her day as early as 4am, would finish her share of the household chores, and leave for the day. “A lot of the housework was shouldered by Ba’s daughter-in-law, my aunty, due to which Mani Ba could follow her calling”, says Professor Patel.

Her ways of teaching were unique – for instance, at a time when corporal punishment was popular, Maniben was staunchly against it. Similarly, she also didn’t believe in burdening children with homework. “I remember one time due to some child’s mischief in class, we were asked to write out each lesson for each subject five times. I came back home and was working hard at it, until Ba saw me and found out what I was doing. So furious did she get that she wrote a scathing letter to the teacher who’d ordered such homework to be completed, reminding him of the philosophies that drive Montessori school education.” She was always more interested in co-curricular activities as a means of teaching students. “She wanted children to cultivate a scientific temper. Even when she played games with them at school, they were always based on the use of some locally produced educational tool. And then she would tell them the history of it. For instance, when she introduced the spinning wheel to us she told us the entire history behind it.”

Not only was Maniben invested in children’s education, but was also concerned about their health, nutrition and development outside of school. For instance, Professor Patel tells me that she paid special attention to all children’s food requirements in school, making sure no child was inconvenienced or forced in any way. The Gandhian idea of “buniyaadi taleem” or experiential education was the basis of her teachings. She would often invite Gandhians like Manuben Gandhi to address the children. In fact, most study tours or excursions were undertaken with the aim to teach. Even when she declined to be the principal of the school, she eventually later became the go-to consultant for any questions on children’s education.

Leading by Example

Maniben revolted against patriarchal traditions of dowry and gender discrimination between sons and daughters during her time. She didn’t ask for dowries from her daughters-in-law, and encouraged her daughters to follow their dreams as much as she encouraged her sons. She was also known immensely for her encouragement of diversity, and for being an open-minded person. Professor Patel recalls that even during her stint with Communism, Maniben did not try to stop her, even if she was a Gandhian herself and disagreed with the ideas presented by Communist thinkers and theories: “Relatives suggested that I be locked up at home, so that I didn’t have access to the outside, and so wouldn’t attend the meetings. But Ba never assented to that. She always said that dialogue fosters understanding. She didn’t believe in using her power to shut anyone up without first letting them have their say. But she never expressed dislike for me. In fact, we would often collaborate on work.” Whenever she practiced her English during those years, she took Professor Patel’s help: “she would lock herself in her room and read aloud to practice, and ask me to pronounce words that she didn’t know how to.”

Maniben played a very significant role in Professor Patel’s life. Not only when she felt different in school, or when she was bullied. She also developed an interest in research due to Maniben’s intense involvement in researching better ways to serve her community of school children. Maniben believed in the Gandhian notion of “paseene ki kamaayi” or sweat labour. She was also a pioneer of the right to education for every child, irrespective of caste or class. She had good rapports with the sweepers and cleaners of her locality, and worked towards getting their children admitted into the Alembic High School, even in environments riddled with discrimination. Maniben accepted all students in her class, even when other teachers refused to admit students with dyslexia or health problems.

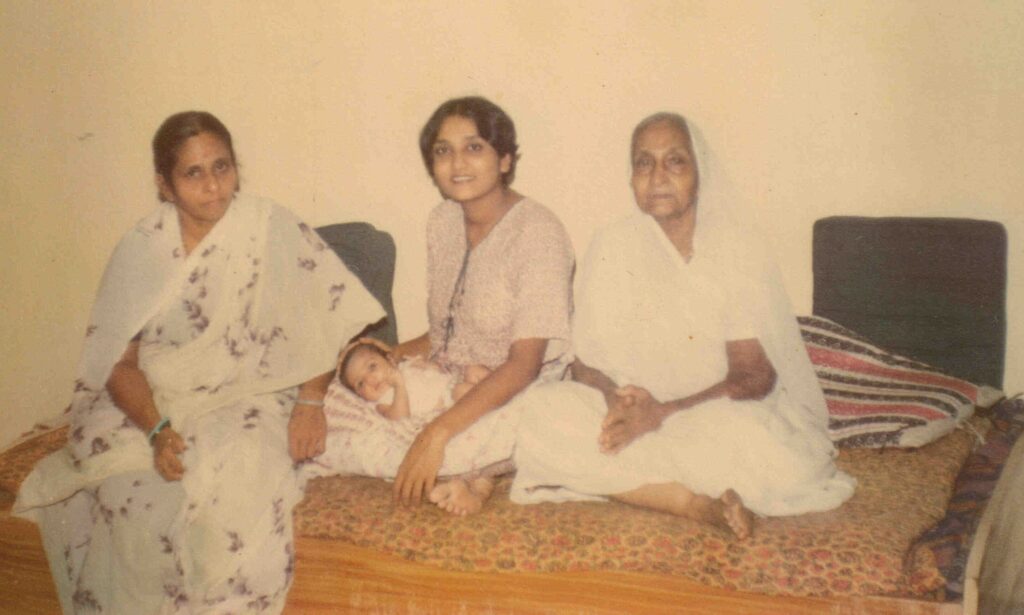

In 1942, under the Quit India Movement’s “jail bharo” campaign, she also went to jail. She stopped teaching in the 70s, and devoted the time till her death in 1987 to being with her children and grandchildren and on catching up with her reading. “She came to visit me when I had my daughter. She hadn’t even gone to visit my mother since her marriage, and she had raised some qualms when I wanted to get married to a Muslim man. But she came and stayed with me for a few days and met my daughter and gave me advice on how to bring her up… it was very lovely”, reminisces Professor Patel.

Also read: Sonal Shukla: Writer, Educator And Iconic Feminist | #IndianWomenInHistory

Maniben lived a very simple life, always looking for ways to serve her community. She was a far-sighted woman, raising her voice on issues affecting women around her – for instance, she was one of the first people to raise the issue of inadequate water facilities affecting women in her locality. Even during the last years of her life, she stayed active, reading and learning, and often consulting teachers in Baroda. She died of a heart attack on 2nd February, 1987.

Contributing Ahead Of Her Time

Maniben lived a very simple life, always looking for ways to serve her community. She was a far-sighted woman, raising her voice on issues affecting women around her – for instance, she was one of the first people to raise the issue of inadequate water facilities affecting women in her locality. Even during the last years of her life, she stayed active, reading and learning, and often consulting teachers in Baroda. She died of a heart attack on 2nd February, 1987.

All pictures’ credit: Mr Baijanath Patel and Ms Anjana Desai

About the author(s)

Himalika is slowly beginning to get the hang of being an adult, despite being a bad cook. She will take most things with a sense of humour and is constantly striving to infuse feminist practices in her research.