In the 1980s in the US, the Environmental Justice Movement emerged in reaction to the discriminatory environmental practices like land use decisions, toxic waste dumping, faulty municipal waste facilities, and how these negatively affected the people of colour. However, the origins of the movement could be traced to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and the environmental movement of the 1970s.

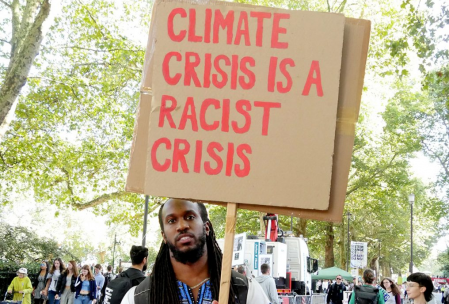

Strong voices emerged from the communities of colour as they started raising their voice against the threats from toxic waste and chemical disposal, citing it as an environmental attack on their civil rights. It was this grassroots activism that gave rise to the term ‘environmental racism.’

Environmental racism refers to how the neighbourhoods populated primarily by people of colour and marginalised socio-economic communities are considered as dumping grounds for waste, as they are burdened with hazardous sources of pollutions and odours that further lower their quality of life.

The term encompasses environmental injustice in a racial context, not just in practice, but also policy, that systemically forces people from oppressed social locations to live in close proximity to sources of toxic waste such as sewage works, mines, landfills, power stations, major roads and emitters of airborne particulate matter.

Officially coined by Dr. Benjamin Chavis, then director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ) in 1982, the term environmental racism was in response to the month-long protest against the siting of a chemical landfill in Warren County. Even though the protest was unsuccessful, it caught the attention of national civil rights leaders and environmentalists.

Chavis describes environmental racism as “racial discrimination in environmental policy-making, the enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of colour for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the life-threatening presence of poisons and pollutants in our communities, and the history of excluding people of colour from leadership of the ecology movements.”

Though originated in the U.S, the term finds its relevance globally, as it can be applied to all multi-racial and ethnic societies that also include indigenous and minority groups, who are more often than not under-represented and excluded from decision-making roles. In the Indian context, the term can be defined as the discrimination reflected in land-use policies and unequal enforcement of rules and regulations, especially against the tribal people and oppressed caste communities

This moment was significant as it shed light upon the country’s history of excluding people of colour from various leadership movements, ecological or economic. It also brought forth how little the lawmakers cared about the racial minorities, thus, exposing them to life-threatening pollutants.

Environmental racism can take many forms in practice, from contaminated drinking water to poor sanitation conditions to workplaces with unsound health regulations. It is true that most of these problems are faced by low-income communities, but a more reliable indicator of systemic proximity to pollution is race.

Also read: The Global Commons: Environmental Sustainability And The Usage Of Shared Global Resources

A study by academician Dr Robert Bullard, the “father of environmental justice,” conducted in 2007 cites “race to be more important than socioeconomic status in predicting the location of the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities.” He proved that African American children were five times more likely to have lead poisoning from proximity to waste than Caucasian children, while even Black Americans making 50-60,000 dollars a year were more likely to live in polluted areas than their White counterparts making 10,000 dollars.

In the U.K meanwhile, a government report found that Black British children are exposed to up to 30 per cent more air pollution than White children. These disparities can be entirely attributed to power dynamics as the millionaires of the country make up only 3 per cent of the entire population, yet control the three branches of the federal government.

Relevance in India

Though originated in the U.S, the term finds its relevance globally, as it can be applied to all multi-racial and ethnic societies that also include indigenous and minority groups, who are more often than not under-represented and excluded from decision-making roles. In the Indian context, the term can be defined as the discrimination reflected in land-use policies and unequal enforcement of rules and regulations, especially against the tribal people and oppressed caste communities.

The issue of environmental racism in India is underlined by three recent controversies in the North East, the dilution of the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) regime via the draft EIA notification 2020, and the plans to auction off forests in central India for coal mining. The Etalin Dam, set to be built in Dibang Valley of the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, is facing a lot of opposition as there is criticism that it would submerge over 300,000 trees and affect several thousand Mishimi people — an indigenous tribal group with a population of 13,000 in the district. Additionally, the dam also poses a hindrance to their right to access their primary site of pilgrimage, Athu Popu, which lies north to the project site.

The protests were silenced by the government with direct violence and the community was completely shunned from the decision-making processes. The protesters were also disallowed from voicing their concerns at public forums.

One of the major reasons why these projects get cleared without any major opposition is the lack of representation and inclusion. Assam, which has almost the same population as the state of Kerala, has 21 MPs as compared to 30 from the latter. Even the largest and most ethnically diverse state of North East, Arunachal Pradesh, is represented by only 3 members in the Parliament

The environmental impact assessment (EIA) for Etalin Dam was carried out by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII). They approved the project after supposedly examining mainly its impact on wildlife. They reported that there were lower wildlife populations in community-managed forests in than the government-owned sanctuary, despite studies that show the opposite.

One more project was given clearance in the same region: the 2,880 MW Dibang Multipurpose Project considered to be one of the largest dams planned in India, likely to displace nearly 2,000 Idu Mishimi people. In fact, over 169 dams have planned in Arunachal Pradesh as a part of a national project. Let us not forget that the state is a biodiversity hotspot, home to 26 major tribes and 100 sub-tribes.

Moreover, the issues concerning the indigenous groups of the country garner neither media coverage nor mainstream public support. For example, not much was covered by the media in the recent Baghian oil blowout in Assam that killed two people, displaced more than 7,000 and had a huge impact on the local biodiversity. Despite public protests, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change gave clearance to seven oil drilling sites inside Dibru Saikhowa National Park, a biosphere reserve.

Meanwhile, in the tribal belt of central India, the Union government announced auction of coal mines to private players in 41 blocks. Many of these mines are located in the Hasdeo Arand region of Chhattisgarh, which is considered to be one of the largest contiguous dense forest stretches in India.

Even though the rural and tribal populations of the country has spearheaded a number of environmental protection movements (Narmada Bachao Andolan, the Appiko Movement, the Silent Valley protest and so on), they continue to be at the receiving end of the discriminatory treatment by the authorities.

The population of tribal groups in India stands at 8 per cent, but they comprise 40-50 per cent of the displaced population in the country. This skewed effect can only be addressed and dealt with when the government stops turning blind eye to the situation and makes room for them to participate in environmental decision-making.

One of the major reasons why these projects get cleared without any major opposition is the lack of representation and inclusion. Assam, which has almost the same population as the state of Kerala, has 21 MPs as compared to 30 from the latter. Even the largest and most ethnically diverse state of North East, Arunachal Pradesh, is represented by only 3 members in the Parliament.

Until and unless the tribal and indigenous communities, as well as marginalised caste groups are given the platform and the opportunity to be included in environmental governance, the age-old perpetuation of environmental racism will not cease to exist.

Also read: Gaura Devi: The Environmental Activist Who Played A Prominent Role In The Chipko Movement

About the author(s)

Taanya is currently pursuing her Master’s degree in English Literature from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Feminist Studies and Postcolonial Studies pique her interest. She reads all genres but has a special liking for LGBTQ literature and women’s writings. Her other obsessions include street food and strong coffee