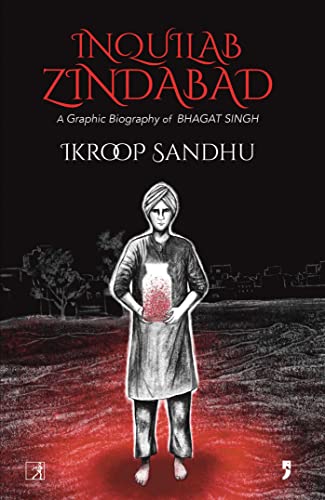

Jointly published by Yoda Press and Simon & Schuster India, Inquilab Zindabad: A Graphic Biography of Bhagat Singh by Ikroop Sandhu is a much-needed, hopeful work in these trying times. While a threat of totalitarianism looms around us, Bhagat’s radical ideas and revolutionary acts described in this book shall serve as a starting point to navigate the test of democracy India is undergoing.

Feminism in India interviewed the author over an email. Edited excerpts:

Q: When was the first time you heard about Bhagat Singh? And what sort of imagery or stories you were told about him?

A: I think my earliest memories of Bhagat are from his photo in history books as a freedom fighter and a few black-and-white films shown on occasion. I don’t remember anyone at home telling me stories about him. I was born in ’82 when India was hurtling towards liberalisation, while its oldest ally USSR was on the brink of implosion. India was beginning to shed its socialist history, fearing the same fate. Children of this era were brought up with a lingering USSR nostalgia on the one hand and, on the other, fresh aspirations of capitalism. I don’t remember any mention of communism or Indian communists while being taught about the freedom struggle in school. Bhagat, Rajguru, and Sukhdev had been absorbed into the nationalist narrative without being revealed as communists or radicals.

Jointly published by Yoda Press and Simon & Schuster India, Inquilab Zindabad: A Graphic Biography of Bhagat Singh by Ikroop Sandhu is a much-needed, hopeful work in these trying times. While a threat of totalitarianism looms around us, Bhagat’s radical ideas and revolutionary acts described in this book shall serve as a starting point to navigate the test of democracy India is undergoing.

Q: Would you mind taking us through the process and research to develop this book?

A: I began working on Bhagat’s biography at the end of 2019, and as 2020 began, the world went into lockdown; there was no chance for me to access any archives. There is an entire Bhagat Singh archive in New Delhi’s Qutub Institutional area, which has been set up by Prof. Chaman Lal. I wish I could have spent some time over there. The best alternative was the Internet. I scoured pictures and scholarly papers on him and his times. There has been exemplary research done on Bhagat in the last few decades. With this book, I’ve collated parts of the research that I felt were relevant or hadn’t yet percolated down into the mainstream.

Q: Any interesting finding(s) during your research about Bhagat or the Indian independence movement that couldn’t make it into the book?

A: Yes, there are many. One was that, apparently, during his time in jail, British families comprising of women and children would come to see him. As a sort of celebrity sighting. He would receive these social visits with good humour, although I doubt if they had any political discussions.

Another finding which surprised me was the story of his uncle Ajit Singh. He lived an extraordinary life, and one could see that Bhagat drew strength from his uncle’s life. I would have also liked to have more pages on the Ghadar Party and movement and their extensive network of revolutionaries across the seas, from California to Mexico to Singapore, to name a few places.

I have stayed true to the subject. I did receive a handwritten message from a very young reader, which said something to the effect that the book made his blood boil, and he wished to get rid of all the British. This worried me a little; I wondered if I had presented a one-dimensional view, and all he took from it was hate for the British. Maybe, I should have emphasised Bhagat’s criticisms of ‘Brown Sahibs’ and the fact that the majority of the police force and judiciary was made up of Indians.

Q: While the book’s front cover says it’s a “Graphic Biography”, your introduction and the back cover refer to this book as a “Graphic Novel”. How do you place your work, and why?

A: I refer to the work as a graphic novel, but the term is still sort of new, and since the very definition of a ‘novel’ is ‘a fictitious book-length narrative’, I believe the publishers may have felt it could mislead people into thinking of the book as more fictional rather than biographical. I will continue to refer to it as a graphic novel on Bhagat Singh because it’s simpler. I have often used the term ‘comic’ as an easy explanation of what it is. However, there is nothing ‘comic’ about the book. I suppose, as the medium becomes more popular, its descriptive vocabulary will also expand.

There were plenty of us who were complicit in the crimes we now attribute to the British. India was and is complex. We never had a monolithic identity, as has been projected by some. There always were small fires burning everywhere, a million mutinies, and scores of rebellions. But, perhaps, for a younger mind, this is not easy to grasp. Bhagat, too began with intense anger towards the British, but as he grew older, he realised that everyone has flaws, and the only reasonable thing to do is to call them out, to initiate a dialogue, a debate to make the world better. That is the reason he threw the bombs in the Assembly, “to make the deaf hear”, and not to merely create chaos.

Q: Because he was often chased by the colonial masters, Bhagat often changed his outlook. Given that this is a graphic work and readers, especially younger ones, are impressionist, what sort of precautions did you take for his graphic representation?

A: I have stayed true to the subject. I did receive a handwritten message from a very young reader, which said something to the effect that the book made his blood boil, and he wished to get rid of all the British. This worried me a little; I wondered if I had presented a one-dimensional view, and all he took from it was hate for the British. Maybe, I should have emphasised Bhagat’s criticisms of ‘Brown Sahibs’ and the fact that the majority of the police force and judiciary was made up of Indians. There were plenty of us who were complicit in the crimes we now attribute to the British. India was and is complex. We never had a monolithic identity, as has been projected by some. There always were small fires burning everywhere, a million mutinies, and scores of rebellions. But, perhaps, for a younger mind, this is not easy to grasp. Bhagat, too began with intense anger towards the British, but as he grew older, he realised that everyone has flaws, and the only reasonable thing to do is to call them out, to initiate a dialogue, a debate to make the world better. That is the reason he threw the bombs in the Assembly, “to make the deaf hear”, and not to merely create chaos.

A: I refer to the work as a graphic novel, but the term is still sort of new, and since the very definition of a ‘novel’ is ‘a fictitious book-length narrative’, I believe the publishers may have felt it could mislead people into thinking of the book as more fictional rather than biographical. I will continue to refer to it as a graphic novel on Bhagat Singh because it’s simpler. I have often used the term ‘comic’ as an easy explanation of what it is. However, there is nothing ‘comic’ about the book. I suppose, as the medium becomes more popular, its descriptive vocabulary will also expand.

Q: You also deftly slip in criticism of the government (e.g., demonetisation) in this work. Was that a deliberate choice, or did that happen during the making of this work?

A: That was a deliberate choice. Initially, I wanted to draw more parallels between the oppressive policies of the British and the BJP. Because near the end of 2019, as I was beginning work on Bhagat, students were being beaten in libraries by policemen, they were terrorised in their hostel rooms and arrested for sedition. The anti-CAA protests were at their peak across the country, and Shaheen Bagh was in full attendance. At that time, a small group from the Kissan union — BKU Ugrahan — had come to Shaheen Bagh and served langar as a gesture of solidarity. A few months later, farmers began protesting in Punjab against the farm laws, which had been passed during the lockdown, and by November 2020, the protestors reached Delhi borders. As I was following the political events closely, it was difficult to not draw parallels. But I soon realised that those were superficial. The BJP has been given an ‘Akhand Bharat’, ripe for receiving their insidious message. The British, on the other hand, had to carve out India from a jumble of socio-political confusion over centuries; they had to wage many wars, annexe many kingdoms, and brutally dismantle revolts and rebellions to turn their colony into a profitable enterprise. And so, I realised that to draw parallels between Imperial Britain and the BJP would not be fair to the former and left it at that.

Q: You have dedicated your work to Samyukta Kisan Morcha. What significance do you place in the farmers’ movement?

A: I have been following the farmers’ movement ever since it began in mid-2020. It was very important to me, as all other voices of dissent so far had been quashed by the BJP. I wondered if the farmers would be able to make an impact. As a middle-class Punjabi, I assumed I knew enough about the rural dynamics of Punjab; I was in for a surprise. As the farmers began marching towards Delhi, their exuberance was infectious. This was the first time I witnessed an organised collection of unions come together to take on the government. The group was without political affiliations and remained adamant about keeping it that way. This came across to me as a challenge to the very core of democracy. If you can organise people based on socialist principles, free from electoral politics in a decentralised framework, then clearly, we need political reforms which encourage communities to come together to decide their workings rather than insisting on individual votes, which go towards centralising power in the hands of a few. I could see that the farmer unions were the closest we’ve come to the ideals that Bhagat had imagined. And so, I felt like paying them a tribute in the form of a handshake with Bhagat.

Q: Do you think Bhagat is misunderstood or not understood at all by today’s youth?

A: I think Bhagat has been simplified into a freedom fighter and a martyr because his message was too radical. He was a student leader who believed that young men and women should be organised to fight the trappings of religion and caste. He was emphatic about having a military wing to oppose the army and police of the State when push came to shove. He was also a socialist and a budding communist. He believed capitalism to be the greatest evil. And he wanted a revolution. A politically aware youth pushing for a revolution is a terrifying scenario for any government. So, it’s safer to show him singing a few nationalistic songs and being hanged for fighting against the British rather than relay his demand for an absolute revolution.

Q: How do you see several groups claiming him nowadays?

A: It surprises me when I see a group like ABVP holding posters with Bhagat’s face. But it also gives me hope. If we all have admiration for him in common, that could be a good place to begin a dialogue. He could be the bridge where the polarised meet. It is remarkable that even after almost a century, his ideas still exude youthful vitality and radical thought. His spectre remains fresh and unburdened in our memories. We can attach infinite possibilities to him, something we can’t with the long lives of political giants like Gandhi, Nehru, or Jinnah.

Also read: In Conversation With Priya Saraiya: From Child Prodigy To Bollywood Lyricist & Singer

Q: What are you working on next?

A: I have been toying with a few ideas here and there. There’s plenty of research material from the time of revolutionaries to tell more detailed stories. But I am also reading about the life of Amrita Sher-Gil in detail. I would like to tell her story in all its scandalous glory. This idea struck me when I saw a couple of fictional short films about her on YouTube, in which she is portrayed as this teacher-type, demure and dutiful, far from the rebellious, critical, sensual person we can see in her self-portraits. Also, here I will be able to experiment with form and colour, which will be refreshing for me after the stark black-and-white drawings I made for ‘Inquilab Zindabad’.

Also read: Durga Devi: The Revolutionary Who Led Bhagat Singh To Freedom | #IndianWomenInHistory

Featured Image Source: The Indian Sun