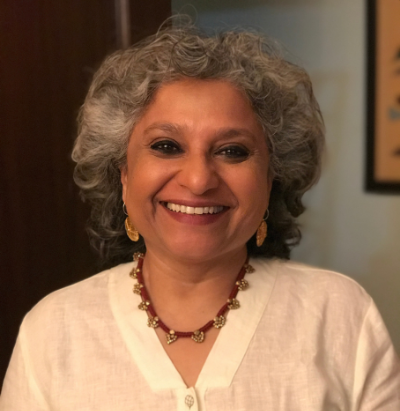

“Economics is a hard nut to crack and the most patriarchal discipline because women are not made to think in a certain way. Standard economics deals a lot with mathematics, equations, and material reality, and women are taught to deal with the material reality in a very intimate way. The basic standards of economics too are very masculine, it only talks about the economic man who takes rational decisions and not the economic woman” – Dr. Vibhuti Patel.

This makes economics hard to connect with for women says Dr. Vibhuti Patel, a distinguished scholar of gender, economics, and women’s studies and a former professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and SNDT University.

Is this true only about economics? Certainly not. There are several other fields like the police services, technical industry, forest services, and others, classified predominantly as “male industries”. Representation of women in these and many such male-dominated industries is an immediate requirement to make it less skewed and have an alternative approach that would accommodate, encourage, and help more women sustain.

As of 2020, only 12 percent of the Indian police force consists of women. Many states have mandated reservations for women in the police force but none of the states was able to meet the desired goal. The representation of women in higher ranks among police services remains even lower.

A survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies reported that many women in the police force find a lack of infrastructural facilities like separate washrooms for women, and lack of venues to report sexual harassment as big barriers to applying for jobs in the police force. The survey also found that several of the personnel were of the view that policing is a man’s job because of the inflexible hours, which affects women’s domestic duties.

The same pattern could be seen in forest services too. As of March 2021, India has a mere 284 women forest officers serving the nation. In an interview with the TOI, women forest guards reported that they cannot leave their houses for long spells given the responsibility of their homes and childcare.

A deputy chief conservator of the forests said that there are no separate toilets for women and they have to share them with men, which is very “hard” and “awkward” for them. These are some of the primary reasons why women stay out of the field duties and opt for desk jobs in the forest services, as reported by the TOI.

The dearth of women in the workforce is not limited only to these fields but is also reflected in the overall Female Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) in India. The female LFPR fell to 16.1 percent in the months of July-September 2020 in India during the nationwide lockdown owing to the pandemic. This is lower than the statistics from our neighbouring Asiatic countries, with Bangladesh’s being 30.5 percent and Sri Lanka’s being 33.7 percent.

There are several reasons for the same, but the most prominent one continues to be adhering to the societal norm that childcare is primarily a woman’s responsibility, says Ajit Ranade, a Pune-based economist, and political analyst. If societal norms play such a huge role in deciding women’s workforce participation, what becomes of the provisions and laws that aim to support women in the workspaces by having crèche facilities, and increasing the maternity leaves?

The Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act 2017, led to an increase in women’s maternity leaves from 12 weeks to 26 weeks, to facilitate higher participation of women in the workforce. However, it had an inverse effect as organisations became more reluctant to hire women of childbearing age, as this would result in their loss. Rather than diluting the maternity leave, it is perhaps important to have a more enabling working environment by providing quality childcare facilities.

Dr. Deshpande calls this phenomenon “the feminisation of students”, where the male to female ratio in classrooms is 50-50, sometimes 40-60 but that does not get translated into jobs. About representation of women in economics, she says “it is still a challenge”. Dr. Patel’s response on economics being a masculine field makes complete sense here. When standard economics talks only about an economic man who makes rational decisions and not a woman doing so, women can become more averse to choosing this field. Moreover, the way women are brought up to deal with material reality also affects their participation in economics, as suggested by Dr. Patel

Dr. Ashwini Deshpande, professor of Economics at Ashoka University, who has also done an extensive amount of research on the economics of discrimination, in an interview to the Scroll, said that women are willing to work but there are reasons why they stay out of the workforce.

“Women are getting educated at a faster rate. But jobs that would be suitable, and commensurate with their qualifications either don’t exist or they are not able to access them. Take transportation. Supposing there is a job in the district centre, and there is a rural woman, how does she get to the place of work? There could be a job, but there is no female toilet there. Things that people would not even consider important constraints, but for women they are”, says Dr. Deshpande.

This indicates the necessity to have an enabling environment for women’s representation in the workforce. Things can be worse when the workplace is male-dominated and apart from the societal norms that hold back women from joining these professions; their safety, and availability of basic infrastructural facilities like washrooms, and safe public transport can act as huge barriers for women.

Another field that experiences lower participation of women is the Indian unicorn sector. According to a report by Sheatwork, a hub for women entrepreneurs, and Techarc; research, and tech consultancy firm; “India will have more than 200 unicorns or startups by 2025 but the growth story will be primarily led by men”.

Women entrepreneurs face major challenges like lack of mentors, absence of infrastructural facilities, and limited access to capital and technology, highlights the report. Women feel that lack of proper infrastructure facilities and lack of funds affect their journeys in the unicorn sector. Nikhil Patwardhan and Moumita Deb Choudhary, write in their article, “Most startups in India are in the technology space and many founders are from top engineering colleges including IITs”.

Although the number of female students in premier engineering institutes like the IITs has gone up from 5 percent four years back to 16 percent, the number of women entrepreneurs doesn’t see a huge boost. The same can be applied to the tech industry. Despite the increase in female students in engineering institutes, their representation in the tech industry remains closer to only 36 percent.

Dr. Deshpande calls this phenomenon “the feminisation of students”, where the male to female ratio in classrooms is 50-50, sometimes 40-60 but that does not get translated into jobs. About representation of women in economics, she says “it is still a challenge”. Dr. Patel’s response on economics being a masculine field makes complete sense here.

When standard economics talks only about an economic man who makes rational decisions and not a woman doing so, women can become more averse to choosing this field. Moreover, the way women are brought up to deal with material reality also affects their participation in economics, as suggested by Dr. Patel.

To make economics more inclusive Dr. Patel says, “feminist economists combat the mainstream economics by making cooperation, and distribution as the basic principles as opposed to the mainstream economics where maximisation of profits is the basic principle. The International Organisation of Feminist Economics is built on the feminist principles of economics where the knowledge is used to support and empower marginalised communities and do responsive gender budgeting, which will encourage more women and people from marginalised sections to be a part of economics as a discipline”.

Another important argument made by Dr. Patel is the need for firms and companies to adopt a cluster approach when they hire women in male-dominated workspaces. “When companies hire one or two women, their voices get silenced and thus it becomes difficult for women to voice up their opinions while the firms get awards for being inclusive. They should follow the critical minimum, i.e. from 33 percent to 50 percent hiring, which will not only increase women’s representation but also give credibility and values to their opinions”, says Dr. Patel

“Gender economics as a discipline has created a healthy curiosity, where right from knowledge construction to the documentation of women’s work in the economy has been legitimised and mainstreamed, and to do so the representation of women in economics is extremely important”, believes Dr. Patel.

“It is also essential to implement the legislation judiciously,” says Dr. Patel. Acts like the Equal Remuneration Act of 1976 make it compulsory for employers to pay equal remuneration to men and women. Articles 14,15, and 21 of the Indian constitution should be strictly adhered to and everyone should be given equal opportunities, equal treatment, and equal reward.

Gender should not be used as a parameter for defining skilled and unskilled labour as what often happens is that women’s work is often categorised as unskilled labour while that of men is classified as skilled labour. She also says that it is important to have committees against sexual harassment at workspaces that should duly do their work, which will encourage more women to enter male-dominated workspaces. Workshops with an interdisciplinary approach should be adopted specifically in male-dominated professions which will increase women’s aspirations across departments.

Another important argument made by Dr. Patel is the need for firms and companies to adopt a cluster approach when they hire women in male-dominated workspaces. “When companies hire one or two women, their voices get silenced and thus it becomes difficult for women to voice up their opinions while the firms get awards for being inclusive. They should follow the critical minimum, i.e. from 33 percent to 50 percent hiring, which will not only increase women’s representation but also give credibility and values to their opinions”, says Dr. Patel.

Dr. Deshpande, in a recent article in the Hindustan Times, wrote that gender norms are no more a monolith in India, and a new survey hints at the grey shades of the ideas of gender roles. Dr. Deshpande mentions that there are certain thoughts like the preference for sons, where the darker shades still exist but it is high time to take cues from the lighter shades to push for equality.

The survey also suggests that 55 percent of Indians believe that men and women make equally good leaders, which suggests that female candidates should be encouraged more to take up leadership roles, although India has been lacking on this front. The darkest shade that this report highlights is the son preference. Dr. Deshpande believes that this gender discrimination in the household gets translated into discriminatory attitudes of employers while hiring women in the workspaces. This attitude can affect women’s workforce participation ratio to a great extent.

To modify this behaviour, it is of utmost importance to take affirmative action to increase women’s participation in the work industry, especially the ones dominated by men like economics, tech industries, entrepreneurial sectors, police force, etc. This necessarily needs to be accompanied by more presence of women in decision-making roles which can result in more legislation and mainstreaming of gender-inclusive, and women-friendly working environments.

Dnyaneshwari Burghate, currently working with Question of Cities, is a post-graduate in Women’s Studies with additional qualifications in media. She is a researcher, photographer, story-teller, and documents stories at the intersection of gender, media and society. She is on Instagram and Twitter

Featured Image Source: The New Yorker

I think Forest service is more hard for woman’s than Police.