Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for September 2022 is Gender and Campus. We invite submissions on the many layers of this theme throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly refer to our submission guidelines and email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

The discipline of Philosophy takes pride in endorsing itself as a critical, discursive praxis. But are its classrooms really free from inherent sexist and heteronormative biases?

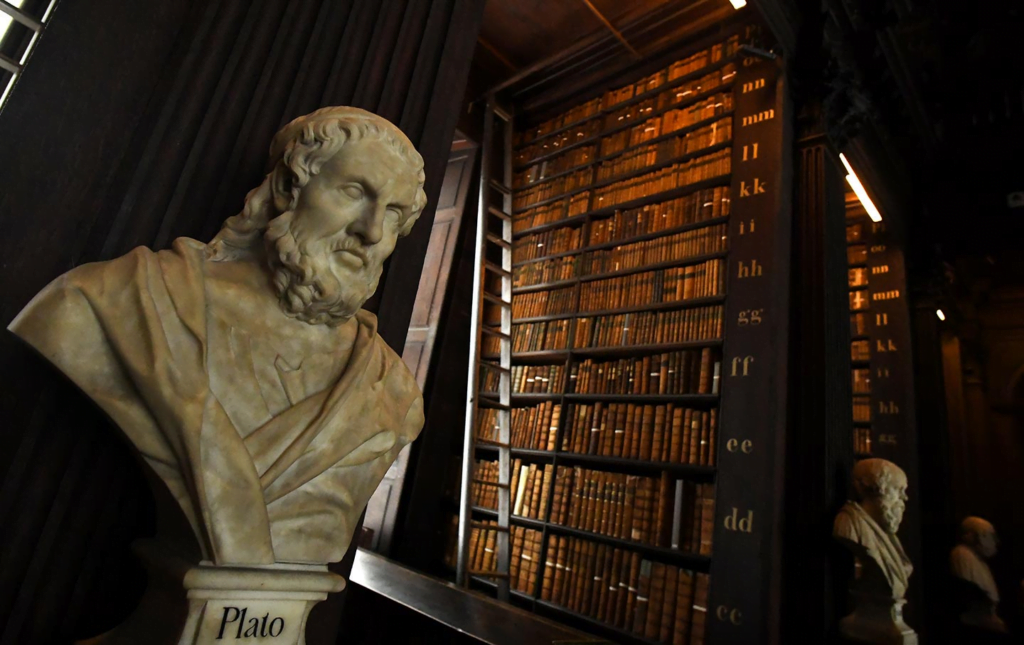

From the concentrated hegemony of male philosophers in the curriculum to the underrepresentation of other genders, philosophy and its lecture rooms have been a mirror image of their time’s patriarchal and oppressive structures.

A huge chunk of mainstream philosophy prescribed in most Indian universities is still constitutive of thinkers who held essentialist biases against women, Indian and Western schools of thought alike. Among them are global, historical canons of the field like Hegel, Nietzsche, Kant, etc.

“A woman is an unfinished man,” Aristotle held. These highly celebrated, revolutionary thinkers validated patriarchal norms that pushed philosophy away from social intersectionalities. Although their misogynist and sexist ideologies are usually kept concealed during discussions for the sake of sensitivity to their scholarly achievements, positionality and context, the dismissal of criticism evoked against their traditional orthodoxy is commonplace in today’s classrooms.

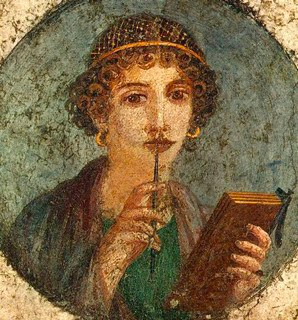

The traditional definition of philosophy – ‘Philo’ (meaning love) and ‘Sophia’ (meaning wisdom), translated to love of wisdom, has historically only welcomed androcentric ideas under the guise of gender neutrality.

Perhaps “wisdom” only entailed normative, majoritarian beliefs that accorded with the conservative principles of the social hierarchal structure. Consequently, critical engagements that posited a challenge to the privileged phallocracies were automatically nudged to the margins.

A common argument that lies implicit in such a view is that men can hoist the epitome of logic and rationale, while women remain embodied and limited because of their sexed bodies. Not only is there a collective failure in realising the human experience as gendered experience, especially in all traditional philosophical branches; the token conversations on gender in classrooms are most often prevailed by the conventional binary, implicitly inferring, in turn, heteronormativity as well

The question of gender is one such example that only came to be discussed after movements of political feminism gained momentum and made room in academia during the second wave of feminism. However, the placement of gender in philosophy has remained bleak and sensitivity towards the issues surrounding gender is very often disregarded.

Feminism and philosophy are often conceded as two irreconcilable fields, despite the increasing developments and achievements of feminist philosophy. “How are issues of feminism philosophical?”, “Why should philosophy include feminism?” – questions of a similar sort are invoked against both students and professors of feminism which demonstrates the underlying impression that philosophy ought to be esoteric, limited to ivory towers and thick convoluted textbooks.

Also read: Understanding Feminist Existentialism

Instead of conducting formal philosophical inquiries along the lines of “the meaning and nature of gender”, “the construct of gender”, “alterity, othering and gender”, etc., the typical philosophical environment has, for the most part, sought to silence these investigations by subtly dismissing them as “not philosophical enough”.

Further, it suggests that feminism cannot become a subject of academic inquiry but rather is only a form of activism, a misfit amidst high-end intellectualism.

Miranda Fricker in her distinguished work “Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing” (2007) coined ‘testimonial injustice’ to denote a credit deficit given to the testimonies/claims of certain interlocutors due to certain biases and prejudice in the hearer’s mind.

One can witness more acceptance of the works and theories of male thinkers under the pretext of value neutrality and objectivity that philosophy has fetishised since its birth. On the other hand, when a hypothesis is problematised from the axis of gender, an obvious apprehensiveness is sensed amongst many professors and students, leading to the text in question getting categorised as “less philosophical.”

In our last semester of post-graduation at the Delhi University, when the class came across Judith Butler’s “Gender Regulations”, some students insisted on reading another paper that they considered to be more important. It was ironic to see how a course entitled “A Critical Reading of Western Philosophy” had mostly male thinkers, and the one philosopher that penetrated this intellectual gender hegemony was potentially disregarded

A common argument that lies implicit in such a view is that men can hoist the epitome of logic and rationale, while women remain embodied and limited because of their sexed bodies. Not only is there a collective failure in realising the human experience as gendered experience, especially in all traditional philosophical branches; the token conversations on gender in classrooms are most often prevailed by the conventional binary, implicitly inferring, in turn, heteronormativity as well.

Thus, gender remains systematically excluded because it hinders the achievement of an absolutist edifice of philosophy by emphasising subjective gendered experiences that further escort analysing oppression from various other axes viz., race, class, caste, etc.

While this is common in lectures of compulsory papers whose syllabi are always, without exception, dominated by male writers, some universities do provide options for feminism through optional papers and certificate courses.

The lectures of these courses quintessentially digress from the typical classroom model; the discussions are both critical and mutual, and the subject matter also invites more student participation as it involves lived experiences of people, struggles and resistance against subjugation. However, the number of cis-het male students enrolling in feminist courses is generally negligible.

In our last semester of post-graduation at the Delhi University, when the class came across Judith Butler’s “Gender Regulations”, some students insisted on reading another paper that they considered to be more important. It was ironic to see how a course entitled “A Critical Reading of Western Philosophy” had mostly male thinkers, and the one philosopher that penetrated this intellectual gender hegemony was potentially disregarded.

In a class of more than a hundred students, few of us also naturally assumed Butler to be a man. Moreover, there was a constant struggle for both students and the professor to use they/them pronouns because Butler identifies as non-binary. Instead, gender binary pronouns she/her were more often used.

Also read: Book Review: The Second Sex By Simone De Beauvoir

Veridically, these theoretical practices are translated in the form of unreported sexual harassment cases on campus and their non-addressal. Such incidents are only known through grapevine channels and often die out on their own due to a lack of safe platforms, fear from authorities, shame and guilt among other reasons.

Philosophy, even in its grandeur of “liberal” doctrines, makes little or no room for confronting gender-based misdemeanours and discrimination.

For philosophy to become truly inclusive, it needs to scrap the ideal of objectivity and acknowledge how this quest of objectivism has led to a totalitarian and oppressive genesis of social-epistemic practices. Its architects usually belonged to the privileged cohort and either remained ignorant or failed to address the material problems surrounding gender.

Simultaneously, the lectures in the universities need to analyse the scholarship of thinkers in a broader context, bringing forth and critiquing the dogmas that they endorsed. This would only be a first step towards identifying that gender issues are philosophical issues, the realisation of which will come through pragmatic, constructive changes, critical discussions and textbooks as well.

Disha is a recent Philosophy post-graduate from the University of Delhi. She is academically inclined towards researching and studying feminist social epistemology. Her two stray cats top her love interests list. She is on Instagram

Hey Disha.

I knew already what’s written in this article,.

First think is that feminism is not wholistic approach.

Feminism have also their branches, like Liberal, radical or more..

In this article you raised a voice over objectification,, I also support you on this,,, this should be stopped. But my question is that where is origin of this?

We all know about pornography, radical feminism support this, in Europe what they are doing, they just want some correction in this institution, they don’t want demolish this. What you think on pronography?

We all know people objectify every gender, what type of male or female should be there,, pornography raising parallel to feminism…

Your feminism walking around academis. But you really don’t know what is going on in village or in other word what is not in academics,,

At last, only paper work can help ? We need do work on earth,, or ground level,,,

Stop embarrassing yourself and read the article before commenting.