Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for February 2023 is Love In Post Modern India. We invite submissions on this theme throughout the month. If you would like to contribute, kindly refer to our submission guidelines and email your articles to shahinda@feminisminindia.com

Indian cinema since its birth has brought along numerous love stories and has inculcated the idea of romantic love marriages in the wider public. But does that hold any bearing with Indians in reality? Love marriages even today are mythical and exist in the imagination only to many. Love in India is often defined by class, caste, race, religion and various restricting power structures.

Often love is a race against family, religion, caste, region and culture. Love marriages even today are frowned upon by many as it is seen as a sign of the youth straying away from religion or culture or both. The bigger problem arises when inter-caste love marriages take place. Most of India’s urban spaces have claimed to have broken the shackles of the caste system away from them. Erstwhile untouchability is almost non-existent according to the urban spaces as claimed in the documentary ‘India Untouched’.

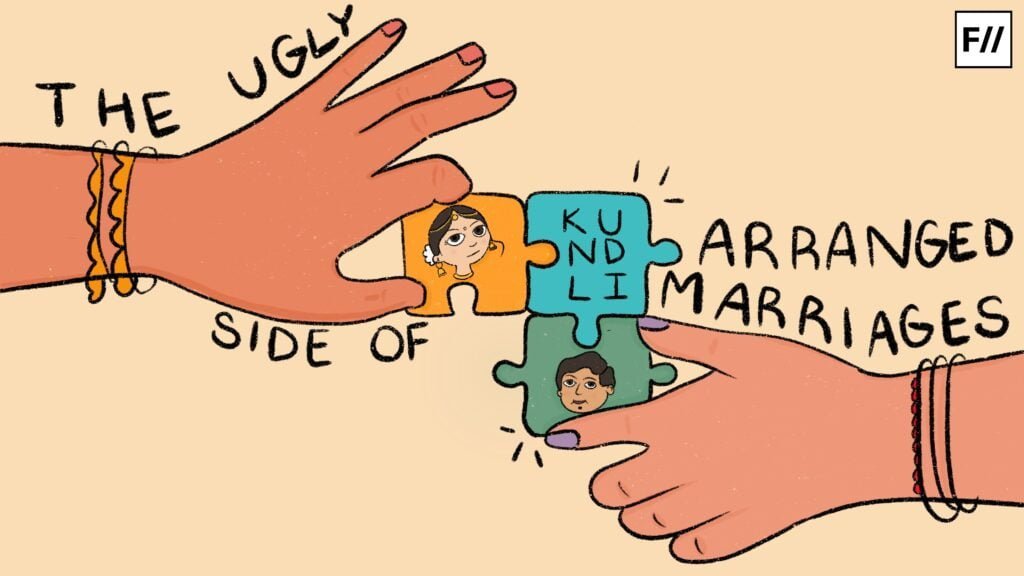

Results of a 2018 survey conducted on over 1,60,000 households note that 93% of married Indians confirmed that their marriage was arranged. Out of this vast data, only 3% of them were married through love and intimate affairs and another 2% claimed to have a “Love cum arranged marriage” which indicated that they met each other through their parents with marriage in mind.

However, Caste is never ignored when seeking an alliance. Caste to date has persistently played an important role in marriages in India. A 2014 survey conducted on over 70,000 people revealed that lesser than 10% of urban Indians claimed that some in their family have married outside of caste and almost none recognised any inter-faith marriages in their families. Today’s younger generation is often projected as willing to marry regardless of caste and religion and take decisions irrespective of normative structures, though, the case is otherwise.

A study conducted in 2015 on over 1000 prospective brides enrolled into matrimonial websites all showed interest in potential partners belonging to their own caste. The study further revealed that a Dalit prospective groom was the least likely to be contacted even with his exceptional educational qualifications and salary.

India’s younger generation can still be counted as being willing to ignore caste and religion while choosing a partner for themselves, however, pulling out the idea of caste from marriage from the older generation still is a much-dreaded task. Thus any act of personal choice against this conservative setting becomes an impulsive act of rebellion and is often dealt with with rage and coercion. Many even today are forbidden to make friends with persons belonging to marginalised castes. In the case of romantic relationships, well, that can lead to ‘honour killings‘.

Marriage for centuries has been an important mechanism through which the age-old hegemonic caste system has renewed itself. Individuals born into a particular caste find alliance within their own groups and then their children go on with this tradition thus containing it all within the caste boundaries and openness to interfaith or inter-caste marriages will be synonymously viewed with the weakening of caste boundaries.

Apps like Bumble, Tinder, Arike play a major role in transforming the matrimonial spaces in India where the profiles are not matched based on caste but based on similar interests and likes. Apps like these do not ask for one’s caste but at the same time do not necessarily ensure a social or legal union will take place. Once the relationship is taken out of the app it harshly undergoes the rules laid out by the community and often dissolves amidst the feud of caste and religion. That being so, it can be argued that dating apps like these only help connect individuals from different backgrounds which result in creating an illusion of breaking down barriers.

However, urbanisation and metropolitanism to some degree have undermined caste. The anonymity of one’s identity in a developing city makes it difficult to act on rules of purity and pollution in the public sphere. Thus lesser activities are then highlighted over an individual’s caste identity. The development of cities is rapidly taking place, by 2030, 40% of Indians are predicted to be living in urban spaces.

The urban middle class once completely occupied by the upper caste is slowly being infiltrated by other backward castes and Dalits, this change is also visible in the marriage market. A study in 1970 put forth that only about 1.5% of matrimonial advertisements in the national dailies were exclusively meant for Dalits and Other Backward Castes (OBC), these figures have increased to 10% in the year 2010. The blending of the so-called upper castes and marginalised castes in the urban spaces have also resulted in the rise of caste or religion-based matrimonial sites like – ezhavamatrimony.com, chavaramatrimony.com, nairmatrimony.com Etc.

However, seeking an alliance in the cities is far different from the one in villages today. It can be noticed that the middle class have shifted from caste and family networks to trusted family friends and professional networks and at the same time rely largely on technology to seek an alliance. Today online matrimonial apps are gradually doing away with caste-based filters. These features and ferocious ambition for upward mobility and economic status show a steady increase in inter-caste marriages amongst the urban middle class. However, the age-old obstacles still remain. From moral policing, and humiliation to honour killings they all do exist even today.

Beyond the families, political parties too can be seen dissuading inter-caste and inter-faith marriages. The very news of ‘Love Jihad’ (A term coined by Hindu radical groups which accuse Muslim men of strategically converting Hindu women by marriage allegedly to weaken the Hindu community) rules set by 11 states across India concretes this notion. These laws prevent Hindu girls from marrying Muslim men.

Conspiracy theories like these put forward by political parties for their vested interests have led to a rift between Hindu and Muslim communities, thus adversely impacting the individuals in marriage from these communities. Against such backlash and regressive rules, some people are still holding on to the ideal of humanism and humility. One such initiative was put forth by Jyotsna Siddarth, Founder of Project Anti-Caste love. She through her foundation promotes unique narratives involving inter-caste/inter-religious romantic relationships.

Also Read: “All Romantic Experiences Are Essentially Caste Experiences”: In Conversation With Jyotsna Siddharth

The complete eradication of the caste system is not foreseen, it still remains a strong demarcation in one’s political and social life. But Caste relations are not rigid and have been witnessing changes over the years as well. With time the boundaries set by caste have weakened when studied in the public sphere.

About the author(s)

Elizabeth has completed her Master's in English at Manipal University. She loves to write and is hopeful about bringing a change through her writings and when exhausted by it she often indulges in films, music and tv shows.