Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for March 2023 is Women’s History Month. We invite submissions on this theme throughout the month. If you would like to contribute, kindly refer to our submission guidelines and email your articles to shahinda@feminisminindia.com

For those who read the original Ramayana, or more likely, those who watched Ramanand Sagar’s 1987 Ramayana T V series, Sita was the epitome of the standards for women. She was chaste, pure, unadulterated, and steadfast, almost always defined by her status as a wife and a daughter. Yet, modern reimaginings of the mythological character are starting to see her with a lot more presence and agency in the story than previously revolved around its main character.

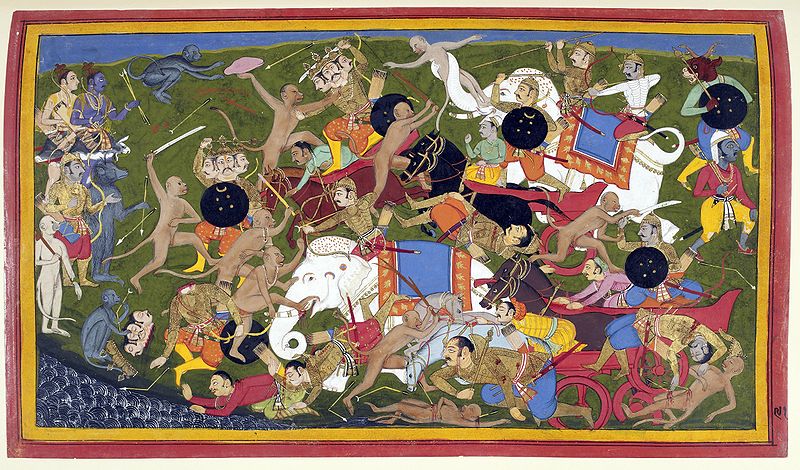

To examine the Sita of present reimagining, it is imperative to see what she was in the past. In the original epic, Sita is introduced during the time of her wedding. After a swayamvar, a gathering of suitors to be chosen for marriage, she is wedded to the Prince Rama of Ayodhya, the only man who successfully strings a god-gifted bow. After a brief time at Ayodhya’s palace, Sita accompanies her husband into exile, where after a set of adventures, she is enamoured by a golden deer, a demon in disguise, and because of this folly is kidnapped by the demon king Ravana. Rama then wages war against Ravana to gain Sita back and vanquish his evil reign.

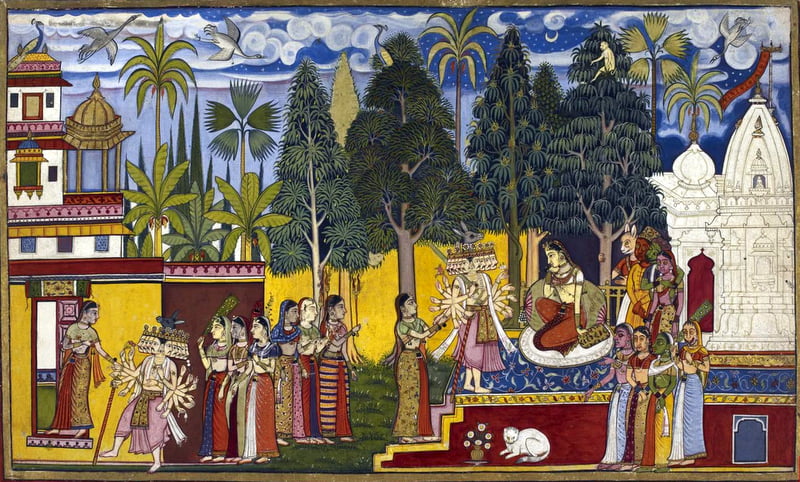

Sita’s story is the perfect damsel-in-distress story, almost perfectly mirroring the Western fairytales of princesses caught in towers, guarded by dragons, waiting for a knight in shining armour to rescue them. Her only moments of agency in the text are when she insists she wishes to follow her husband into the forest, a depiction of her as the self-sacrificing wife, and when she insists that Lakshman leaves her unprotected, hence falling prey to Ravana. Her most valued trait is when she refuses to wed Ravana in the palace of Lanka, insisting on her faith in her husband and hence maintaining her chastity. By any interpretation, she is the epitome of the female ideal.

Feminist criticism of the portrayal of Sita in the Ramayana is ever-present. The androcentrism of the narrative, in particular, has been written about plenty. With most of the story being an uncontroversial battle between the forces of good and evil, Sita is not even a participant, she is what is being fought over. At most, she is a plot device to further the story, instead of a complete character of her own. Her moments of agency, too, are often used as an allegory for the fallibility of strict moral codes.

Also Read Queens Of Kashmir: How History Depicted Them As ‘Immoral’ & ‘Power Hungry’

Sita falling for the illusion of the golden deer and insisting her husband capture it is seen as her falling for Maya, the illusionary force that draws one away from their ultimate goal. Sita’s crossing of the Lakshman Rekha, a line drawn which does not allow for demons to cross, is seen as a metaphor for her crossing the bounds of morality.

This does not make sense within the context of the text, of course, given that Sita has crossed this line as what she considers a sage has threatened to curse her family if she did not. Yet, modern and ancient interpretations of the text have always included this implicit criticism of Sita, and a tendency to blame her for the tragedies she would have to face.

Modern interpretations of the Ramayana have changed this male-centric lens on Sita, instead either perusing the Ramayana from her perspective or completely changing her character, making her an active character in her destiny. The first woman to rewrite the Ramayana, Chandrabati, retold the Ramayana from the perspective of Sita, only interrupted by the author’s suicide. Retelling a fragment of the Rama tale from the perspective of Sita, Chandrabati’s Ramayan begins from the birth of Sita instead of that of Rama, and details the anguishes of her life.

Also Read: Why Is Soorpanakha’s Sexual Agency Demonised When Menaka & Shanta’s Is Not?

The battle, which took up a majority of space in the original Ramayana, only takes a few lines in Chandrabati’s Ramayana, which instead focuses on Rama and Sita’s interludes in the forest. It is a text written by a woman, for a female audience, which subverts every aspect of the book.

More modern reinterpretations of the Sita myth take place in books such as Sita: Warrior of Mithila, where Sita walks with weapons and does not flinch at the sight of blood. Here, Sita is a leader and a warrior, instead of the passive Sita of the original text. Other reimaginings include Devdutt Patnaik’s Sita, Ashok K Banker’s Sons of Sita, Samhita Arni’s The Missing Queen, among others.

Perhaps meant for the expanding female audience, as well as to fit along the international trend of mythology reimaginings (The Song of Achilles, Circe, and others are notable examples), these books have taken over the Indian market by storm. Women in the newer interpretations of the Sita mythos play a larger role in not just the plot, but also the narrative themes of the text, establishing a larger role than just their perfect submission.

Several contend that this form of reimagining of the original mythos is a perversion, rather than an interpretation, removing the true meaning of the text from popular consciousness. This is also interwoven with the idea that several members of the Hindu community, as well as Hindu nationalist rhetoric purport that the events of the Ramayana are not simply story and myth, but actual, verifiable truth. While it may make sense to purport that stories can be reimagined, for the critics of the modern Sita, the reinterpretation of Sita is a 1984-style perversion of history and traditions.

However, mythology is almost always a base for culture to form, and it always evolves over thousands of years of its existence. The Ramayana has already collected a veritable library of interpretations across geographies, as it travelled to what is now South Asia and South-East Asia. The characters of these varied stories are not the same, instead reimaginings according to the author and the culture they inhabit. Mythology reflects the culture of its time and place, and modern reimaginings of the Sita myth are nothing more than that.

For young women across India, Ramanand Sagar’s Sita was some sort of heroic figure in their childhood, someone they should look up to and aspire to be. From Sita, women learned the oppressive ideas of the past: subservience, chastity, and humility.

Also Read: Women In Hindu Mythology: Is Their Space Too A Myth?

Modern Sita is a new role model for the women of the present, women who have taken the feminist movement and applied it to their lives as well as their stories. Given that mythology of the past was almost always written and passed on through patrilineal legacies, women entering into the intellectual space and writing stories for other women, with the characters they want to shape their culture, is a step into the future. Perhaps young women who are reading and watching newer versions of Sita will have a role model to look up to that is strong, independent, and has agency in her own life.

Poor interpretation. It says next to nothing about 300 Ramayanas that have been written, nor does it talk of the oppression which she undergoes like King Ram seeking her to prove her purity, she being banished to the jungles, and her ultimate samadhi (suicide?)