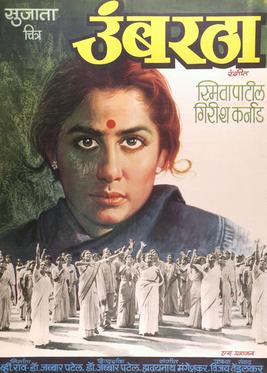

Umbartha is a Marathi language blockbuster film that almost everyone would have heard about for various reasons. Maybe it was because the lead actors Smita Patil and Girish Karnad were very popular, maybe it was because the director Jabbar Patel enjoyed an extremely good reputation amongst the audience or maybe because it had songs like Gagan Sadan sung by Lata Mangeshkar that can still be heard in homes.

However, the most distinctive and striking feature of the Umbartha was its poster. A 1982 film poster dominated by the face of a woman who does not look like then-associated characterisations of being feminine and has a determined look and aura of authority around her and around her there are small figures, all women! This is the most intriguing element of the film – a woman trying to exercise her agency and enabling other women to do the same is what sets Umbartha apart from other films of the time.

At one level, it is the story of a lady who is attempting to exercise her agency by stepping out of her family where she does not think she belongs to contribute to improving the lives of destitute women. At another level, it is also a story of how women who have in some way or other been wronged or have suffered the brunt of patriarchy and ultimately found their home with other women like them.

At the end of the Umbartha, even Sulabha becomes one such woman and these other destitute women become her family. Additionally, it is an attempt to expose the individuals and parties who try to fulfil their own interests and selfish objectives in the name of philanthropy and systematic corruption which at times costs individuals their lives.

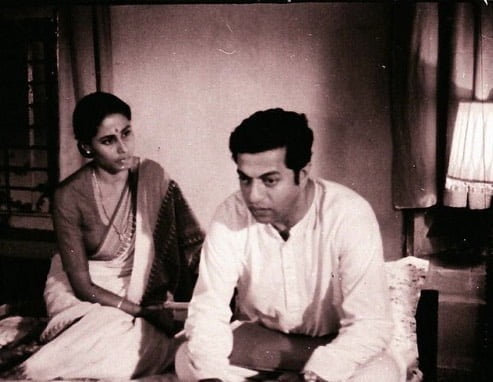

At the very beginning of the Umbartha, we get a sense of the kind of character Smita Patil is about to portray. The film starts with Sulabha roaming around alone, people in her family seem to be busy. Despite this, we feel that she is lonely and get a sense of what she later says, “I do not belong here“. With the degree she gets in sociology, a drive to do something for society and women, fuels Sulabha’s every action. Her husband Subhash, who supported her to take up this course shows his inherent patriarchy when he taunts her for not being understanding, not doing anything for the family and claiming that her attitude seems to have changed after the course.

This was the initial aim of keeping women away from education and restricting them from exercising their own individuality distinct from their personal and emotional ties. Therefore, the portrayal of this idea that a woman, who has a seemingly understanding husband, and a decent family wish to have something more, does something more and does not feel like she belongs is very modern.

Sulabha does not fit into the usual characterisation of being a soft-hearted mother as she chides her daughter while her sister-in-law and brother-in-law seem to be spoiling the kid with excessive affection. Her sister-in-law fits in the characterisation of being a perfect wife, supportive sister-in-law and a caring motherly figure for her niece Rani. However, a taunt that she receives from her mother-in-law initially as to what level of affection she would have bestowed had Rani been her own daughter, immediately draws attention to the fact that no matter what kind of affection she shows towards the child, she herself will always be childless.

In this context, Sulabha’s mother-in-law is an interesting character, she is the authoritative figure and head of the household but she is not an exception to the patriarchal norms. She works, but as a woman from a sanskari family, she knows her limitations. Thus, Sulabha is trapped in a household that supports stepping out of home but opposes the idea of leaving home.

Also Read: Ankur (1974) Through A Dalit Feminist Lens

When Sulabha receives her dream job offer from a women’s reformatory home that is away from her place, she faces resistance from her mother-in-law and her husband, Somehow, managing to convince her husband, she is finally able to leave her home. Here, the character of a pseudo-modern husband comes to light. While he ‘allows‘ his wife to take up the job offer, he is often seen reminding her of this ‘favour‘.

In line with this perception, Sulabha also feels obligated to thank him. At the end of the film, one would be horrified to see that the husband asks Sulabha to compromise and accept the other woman in his life as he also understood her job ambitions and adjusted to them. Here, we see, the man who was all for family emotions and everything in the start just reduces the understanding between the couple to give and take, he simply attributes a transactional value to it.

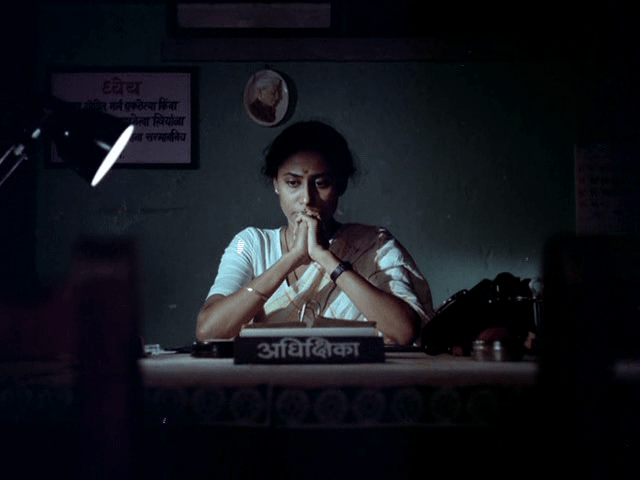

Umbartha takes on its second major theme, once Sulabha joins the reformatory home. The film does not just deal with the political aspects of feminism but also the politicisation of social causes and philanthropic issues. It brings out the usually covered angle in Bollywood and regional cinema that highlights the corruption in bodies, organisations focused on social issues and supporting eco-system that consists of corrupt officials and politicians.

The moment Sulabha enters the home, she is surrounded by numerous challenges, the inmates have some internal hierarchy, officials simply do not care, there is embezzlement of funds and the helpless women were “supplied” by Sulabha’s previous superintendent to the local MLA. When brought to the notice of the chairman, she adopts a high-handed approach, no one seems to be caring about the lives of the women or bringing about a positive change.

In fact, blame is pinned on the newly joined Sulabha who stands different in terms of her opinion. Sulabha appears as a strong woman as she strictly brings the home under discipline, makes sure what supplies are meant for the inmates, reaches them and is not exploited for or utilised by anyone else, the other intermediaries like the police, and the rest of the staff. At the same time, she is affectionate and appears as a motherly figure to the inmates of the home, thus, her character here explores dual strands of femininity.

Then, comes the theme of destitute women finding solace in each other’s company. All of them are involved in the internal politics or hierarchy issues of the care home, but ultimately, they are all women who have nowhere else to go, as Kamala bai says, “I have no home“. This statement also highlights the plight of reformatory homes which are just homes in the name of it. Two women even try running away, for them, they were brought from one hellhole to another hellhole.

Another interesting episode in Umbarthais that of Lesbianism. The inmates, watchmen and the staff see two women together and express absolute disgust and horror. One can even sense that these women sense some level of betrayal as having been imparted to them. Because it is not something that was common in society at that time women do not even have the vocabulary to describe what they saw. As for those two women, they suffer from a double disadvantage.

First, they are destitute women, secondly, they are women who love each other. They are subjected to verbal and physical violence, but physical violence is more targeted at masculine-looking woman. This might be because she is the “other“, initiator of the “immoral liaison“.

Also Read: Pyaasa (1957): The Good, The Bad And The Ugly Of It

At the same time, these are the women who have suffered from destitution because they were shunned by society, so, one expects them to be more considerate. But that is not the case. In this situation, Sulaha represents a pseudo-modern perspective as she attempts to understand these women but her behaviour shows that she has never seen or personally witnessed lesbian love, maybe, that is why when she is talking to the committee chairperson, she talks about getting them treated from a psychiatrist. A Publisher who is part of the committee publishes an article about Lesbianism and sees it as a source of entertainment. And the Chairman, being as inconsiderate as always says, “what are you defending Mrs Mahajan?“

Moreover, throughout the film, women of the reformatory home are stripped of their consent. They are sometimes thrown out if the authorities wish to do it. The preference of a woman not wanting to use her husband’s name is not just disrespected but is a laughable stock for committee members. When Sulabha talks about increasing opportunities for self-employment and training for these inmates, the management committee ignores her. This nexus does not care about what happens to those women, these women are not asked about their consent at all when arrangements are being made for them.

Sulabha, on the other hand, sympathises with them and believes that snatching freedom to improve people or transform lives is not going to work and that everyone deserves a second chance at leading a basic, decent life. This becomes clear at the end, before resigning she comments, “the status of the home is not more important than the women living in the home”

Comments like “what better can one expect here” on drinking a slightly decent tasting tea at the reformatory home, just shows how people see these women and anything associated with them. All in all, one cannot deny that here, intersectionality comes into play as quite particularly women belonging to certain sections are targeted and their existence is criminalised to this attribute and a singular identity.

Additionally, Sulabha’s husband stands to symbolise the apathetic attitude that people have towards others, particularly disadvantaged and socially unacceptable women. Her husband, for instance, takes up a case where he defends a doctor who rapes a woman simply by painting the woman’s character in a bad light and bringing out her poverty. This so simply done “character defamation” is a recurring theme in the film, even after the lesbianism of two women is found by other women, they start commenting on their character and this is so easily done that it reduces the gravity of the issue.

Also Read: Kanakam Kaamini Kalaham: An Absurd Comedy Drama With An Interesting Gender Lens

Moreover, women who are deceitfully impregnated by men are shamed as being characterless. The general attitude of people who are not directly involved in this is, “I don’t care, but I will judge and comment“. Comments like “what better can one expect here” on drinking a slightly decent tasting tea at the reformatory home, just shows how people see these women and anything associated with them. All in all, one cannot deny that here, intersectionality comes into play as quite particularly women belonging to certain sections are targeted and their existence is criminalised to this attribute and a singular identity.

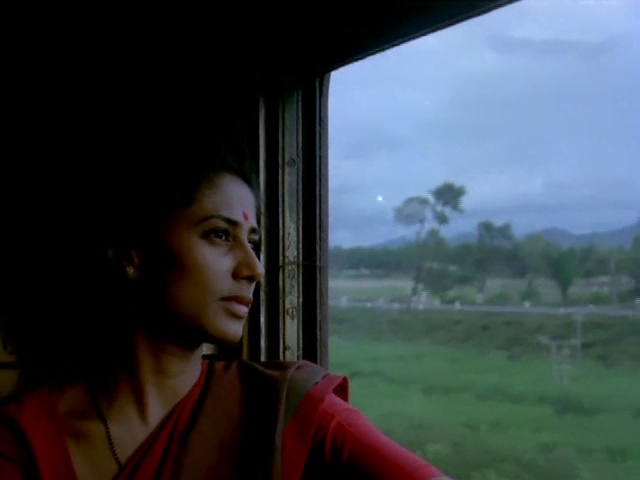

All in all, as the name of the film Umbartha meaning Threshold suggests, it is a story of a woman stepping out of her home, exploring the world and her interests while she faces challenges and resistance. In the end, when she returns home, her family has moved on, and gotten used to living without her, she feels even less belonging than earlier and she decides to leave her house for good.

Ironically, Sulabha ends up becoming one of those women she helped but what differentiates her is her stoicism. We as viewers, never know what Sulabha does after this, there is a sense of sadness at what she is going through but the final clip of Sulabha sitting on a train with a satisfied smile emits an aura of freedom and a sense that whatever path she will choose, she will get to do what she wants.

About the author(s)

Arya is an undergraduate student pursuing an Integrated Master's in Development Studies from the Indian Institute of Technology, Chennai. She completed her schooling in the humanities stream from Nagpur. Still hooked to teenage novels, she likes singing, dancing and loves talking. Intersectionality became her favourite word since the time she was introduced to it. Her major interests include adopting the intersectional feminist approach in studying other disciplines like Economics, Management, Development and interpretation of literature, films Etc.