The sphere of print and literature has historically been occupied by the dominant groups in society and articulates their social outlook and concerns. As found by Orsini (1996), in north India, before the 1920s, Hindi writing and literature were limited in their scope, agenda, participation, and readership. However, she notes that the growth in literacy and printing culture in the 1920s and 30s engendered a proliferation in texts of Hindi literature, leading to the formation of what has been noted by historians as the ‘Hindi public sphere,’ marked by the launch of several literary journals, political weeklies, and dailies.

Within this, Allahabad in UP emerged as the centre of Hindi literary activity (Gupta, 2020.) The writings and literature produced were not independent and embodied the move towards the creation of a culturally consolidated nationalist identity.

Yet, this unified whole was often fractured by marginalised voices, that accommodated the plurality of experiences (Orsini, 1996). The production of vernacular literature and the emergence of Hindi women’s journals and the evolution in their content stands testimony to this.

While writings by women largely echoed the values of the dominant patriarchal nationalist discourse, they also acquired an autonomous force; they wrote on a variety of issues like education and family, imbuing a sense of subjectivity in their work. The result was a changed understanding of women as individuals with their own feelings, opinions, and resolves. However, like the women writing in these journals, the concerns and views reflected in them were primarily those of the upper-caste, middle-class groups, and excluded the experience of women from marginalized sections (Orsini, 1996).

Ayurveda in the hindi public sphere

The boom in print culture begot another transformative trend – the interaction of oral indigenous knowledge systems with the written medium on a mass scale. As such, Ayurvedic knowledge, through writing, now reached the public. In 1934-35, from UP alone, there were about twelve Hindi journals published about Ayurveda (Gupta, 2005.)

On the one hand, these texts transferred Ayurvedic awareness to the masses, and on the other, because of the ancient nature of their knowledge, became a conduit for the consolidation of a Hindu national identity, harping for a return to the golden age of the Vedas. These writings also articulated the changing relationship between Ayurveda and the colonial state; Ayurveda was no longer the object of Orientalist curiosity.

Some texts called for the urgent preservation of the Ayurvedic tradition, while others adopted a more syncretic approach, and integrated Western medical science insights and methods into their writings. Within this overwhelmingly male space of Ayurveda, women had existed as informal indigenous medical practitioners in households, and as midwives (Gupta, 2005.)

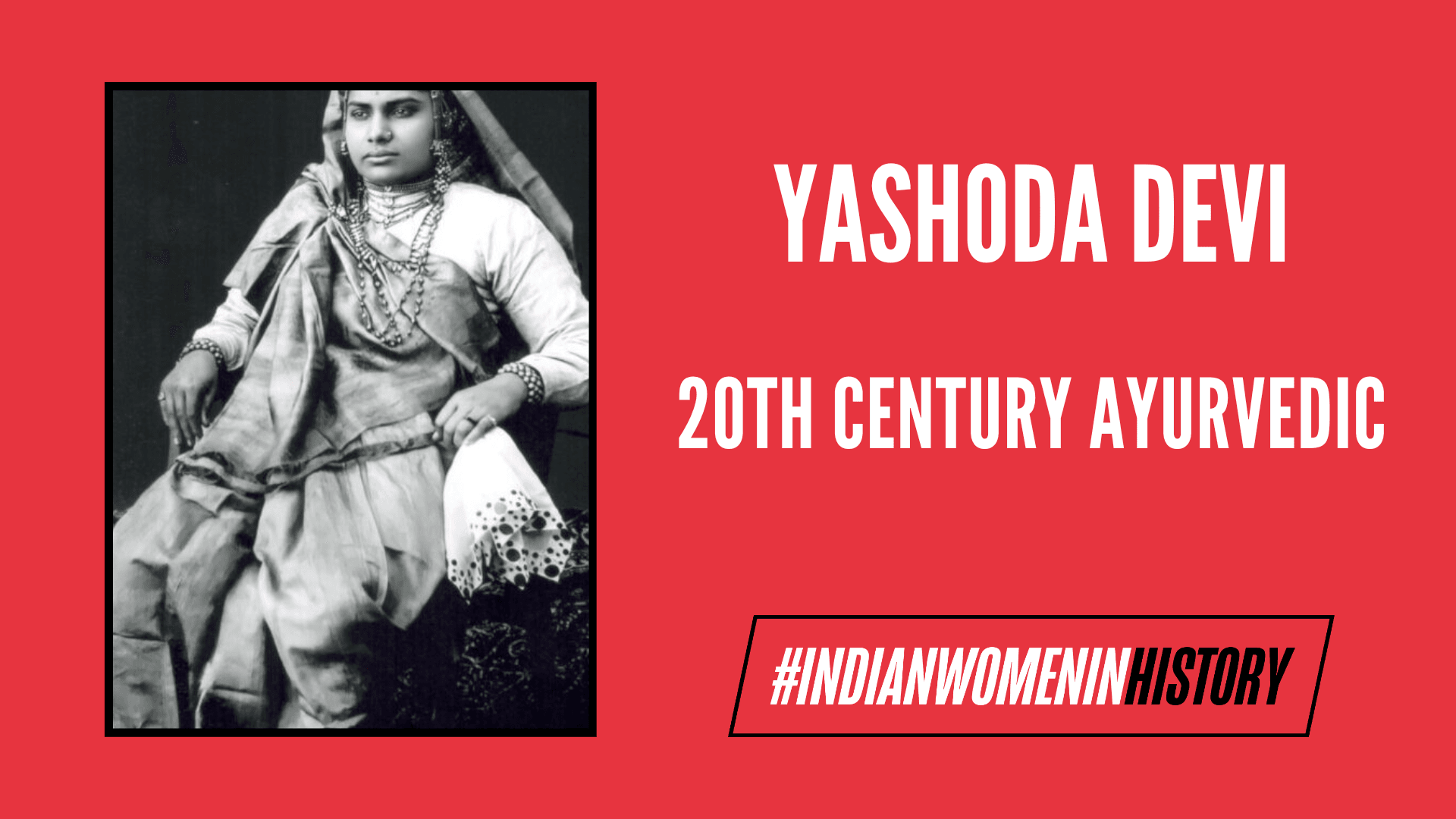

It is between this invisible domain of domestic healing, and the formal, male, public domain of Ayurvedic pedagogy, that we can locate the work of Yashoda Devi.

An ayurvedic and moral sexologist

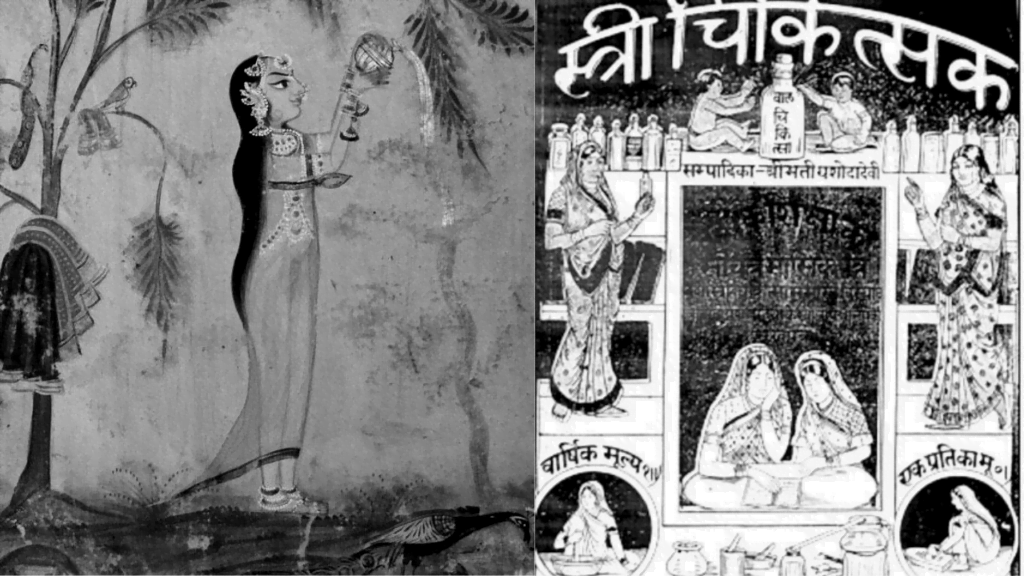

Gupta (2005) notes that Yashoda Devi acquired her Ayurvedic knowledge and training from her father, and established the first Stri Aushadhalaya (Dispensary for Women) in Allahabad around 1908, opened a female Ayurvedic Pharmacy, and a publishing house, ‘Devi Pustakalya,’ printing more than fifty books dealing with issues of women’s sexual health.

Further, she found that Devi’s most successful journal was the ‘Stri Chikitsak,’ with a circulation figure of about 5000 a month; it provided exclusively for Ayurvedic treatment of female diseases. Devi had masterfully utilised the boom in commercial publishing to spread the knowledge of Ayurvedic healing.

Within Ayurveda itself, there had been little concern about women’s health and diseases, and it was this space that Yashoda Devi claimed to carve out, dominate, and expand into the public by studying menstrual bleeding, miscarriages, vaginal discharges, and sexually-transmitted diseases (Gupta, 2005.) Despite her popularity, she was ruthlessly excluded from Ayurvedic circles like the Ayurvedic Mahamandal and Mahasammelan (Gupta, 2020.)

Also Read: Muktabai’s Contribution To Bhakti Movement And Protofeminism

Explicating the writings of Yashoda Devi

Devi’s writings can also be placed within the ambit of vernacular sexology literature being produced in early 20th-century north India – yet another male-dominated space. The study of sexology literature in this period is also the study of the interaction and conflict between colonial and indigenous attitudes towards sexuality. Moreover, deriving from the Kama Shastras, they reinforced Brahminical understandings of gender and caste; and yet, the vernacularisation of such texts also allowed marginalised groups to manipulate them for their own use.

Hence, while Yashoda Devi’s own writings echoed these Brahminical traditional hierarchies, they also utilized the narrative of Ayurveda to challenge male sexual privilege and patriarchal scientific authority (Gupta, 2020.)

Devi’s work stretched beyond medical concerns into the realm of social prescription, domestic management, conjugality, and morality. Her writings aligned with the nationalist rhetoric of an idealised woman who was educated about managing the home and thereby the nation (Gupta, 2005.)

Considering a lacuna in knowledge about the needs of women’s sexual health concerns, for research, Devi employed scientific tools like extensive questionnaires and personal examinations combined with more informal methods; her personal interactions with women, and the detailed letters they wrote to her, allowed her to address more social problems like rape and their implications on women’s sexual and psychological health.

Through such interactions, she attacked notions of Hindu male sexuality. Thus, while her work sought to control female sexuality, it also emphasized the need to control male sexuality, critiquing male sexual behaviour, and its undisputed acceptance (Gupta, 2005.)

In this process, Devi fervently revolted against non-consensual sex and championed the cause of the sexual agency of women. Further noting the brutality of male sexual habits, her writings cited the lament of several of her female patients whose husbands demanded sex despite their repeated refusals.

Devi also raised her voice against the sole victimization of women for issues of infertility, arguing against masturbation and excessive sexual activity as a waste of semen and energy. Her attempt at regulating the frequency and conduct of sex was not isolated, but a part of the discourse of national identity which glorified values of sexual abstinence and discipline (Gupta, 2005.)

While Devi focused her work on women’s fertility issues and fixated on the procreative function of sex, she used its narrative to destigmatise the negative connotations historically attached to female sexuality and women’s sexual pleasure. A happy, conjugal life, according to her, required the participation of both the wife and husband, and thus she emphasised the need for the woman’s sexual arousal through foreplay, and her agency in setting the pace of sex.

By talking about the private act of sex publicly and foregrounding the concerns of women, she broke down the barrier between the domestic and the public sphere (Gupta, 2005). It is this division that had relegated the experiences of women to the private, thus rendering them as personal matters of the household, not to be voiced in the public. Furthermore, Devi conveyed complex Ayurvedic knowledge in simplistic language and thus managed to reach the less educated women as well (Gupta, 2020).

However, in light of a lacuna in knowledge about the needs of women’s sexual health concerns, she also adopted more informal methods; her personal interactions with women, and the detailed letters they wrote to her, allowed her to address more social problems like rape and their implications on women’s sexual and psychological health. Through such interactions, she attacked notions of Hindu male sexuality.

Also Read: Kailash Puri: Punjab’s Forgotten Sexologist | #IndianWomenInHistory

The dichotomy of resistance

On the one hand, Yashoda Devi’s story is of a woman who overcame the limitations placed on her gender and subverted sexual norms. She carved out an exclusive and safe space for women to express their sexual concerns and give voice to the vices of their husbands. She encouraged women to venture out of their homes to seek treatment, write detailed letters to her describing their problems, and had a rest house where women could come and stay for the duration of their treatment, providing them with a space outside of their homes (Gupta, 2005.)

On the other hand, she was constrained by her biases about sexual behaviour and echoed dominant heteronormative perceptions. Her narrative appears fractured by vehement arguments for the procreative function of sex, disciplining of sexual bodies, opposition to masturbation, and homophobia. We cannot overlook these fallacies, but it would also be unjustified to deny her contributions to offering a gendered perspective on issues of health, marriage, and sex (Gupta, 2020.)

These contradictions have relegated her work to relative obscurity in contemporary times. However, these ambiguities are significant as they embody the dichotomous nature of resistance. They reiterate the need to look at and study the resistance coming from the margins and recognise their agency in foregrounding new categories of analyses, thereby making our study of the past more realistic and holistic

References:

1. Gupta, C. (2020). Vernacular Sexology from the Margins: A Woman and a Shudra. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 43(6), 1105-1127.

2. Gupta, C. (2005). Procreation and Pleasure: Writings of a Woman Ayurvedic Practitioner in Colonial North India. Studies in History, 21(1), 17–44.

3. Ishita, P. (2020). Introduction to ‘Translating Sex: Locating Sexology in Indian History’. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 43(6), 1093-1104.

4. Pande, I. (2018). Time for Sex: The Education of Desire and the Conduct of Childhood in Global/Hindu Sexology. In V. Fuechtner, D. Haynes E., & R. Jones M., A Global History of Sexual Science, 1880-1960. University of California Press.