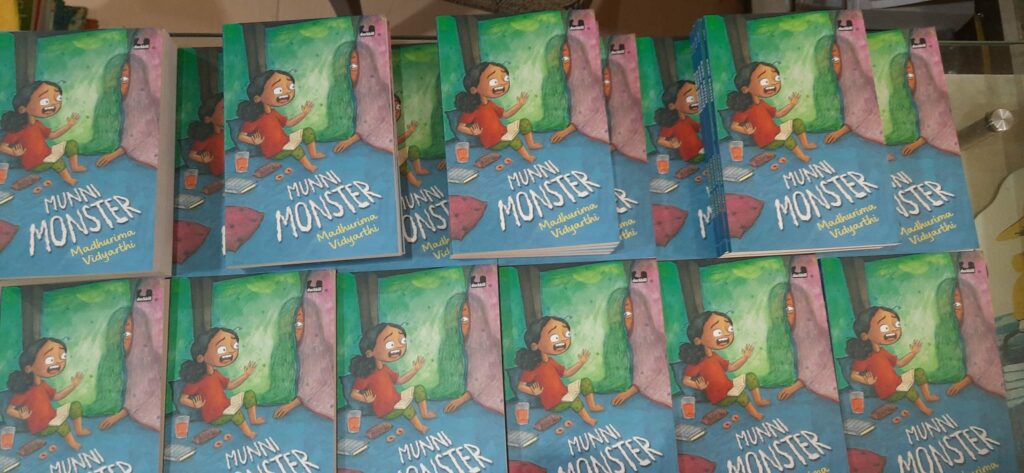

For children aged nine and above, Madhurima Vidyarthi’s Munni Monster (Duckbill Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, 2023), illustrated by Tanvi Bhat, is a humorous, tender, and moving story.

The book begins with everyday interactions in a middle-class household, but one day the news of a death in the (extended) family brings with itself a responsibility: to take care of an old woman Munni, who is diagnosed with cerebral palsy. As a result, our protagonist, a young girl named Mishti is disappointed and, along with her mean, privileged friend Riya, starts thinking about ways to protest against Munni’s presence in the house.

However, another conflict is waiting to unfold in this heartwarming story which changes things for good. What’s perhaps the most endearing quality of this book is that it can tread the fine line between preaching and loosely narrating a sensitive story. And, in particular, because it’s written for children, it’s all the more important that this book helps provide language to talk about cerebral palsy, disabilities, and grief for young readers.

In a conversation with FII, Madhurima Vidyarthi discusses what inspired her to write this book and how easy/difficult was it to weave this narrative for her target audience.

FII: You are an endocrinologist who always wanted to be a writer. I want to know what a day in your life looks like. As someone with another, demanding profession, how do you carve out time to write, especially sensitive literature for children?

Madhurima: My day starts very early, with the school run and back-to-back clinics till about late afternoon, ending again with school pick-ups. After COVID, patients have discovered the joys of remote consultations, which takes up the other half of the day. Again, interspersed with the usual school-home-family type activities. Online consultations are flexible where time is concerned, though. So, I usually get a clear stretch where I can write. But otherwise, I also actively pursue research for ongoing projects or if there is editing to be done, I will do that, although it’s not my favourite job.

To answer your question about sensitive literature, I feel it’s more a question of projects choosing me than the other way around. What I do know is [that] however attractive the topic [is], if I don’t feel an irresistible urge to write it, I can’t and if I force myself to, it becomes a really badly written story.

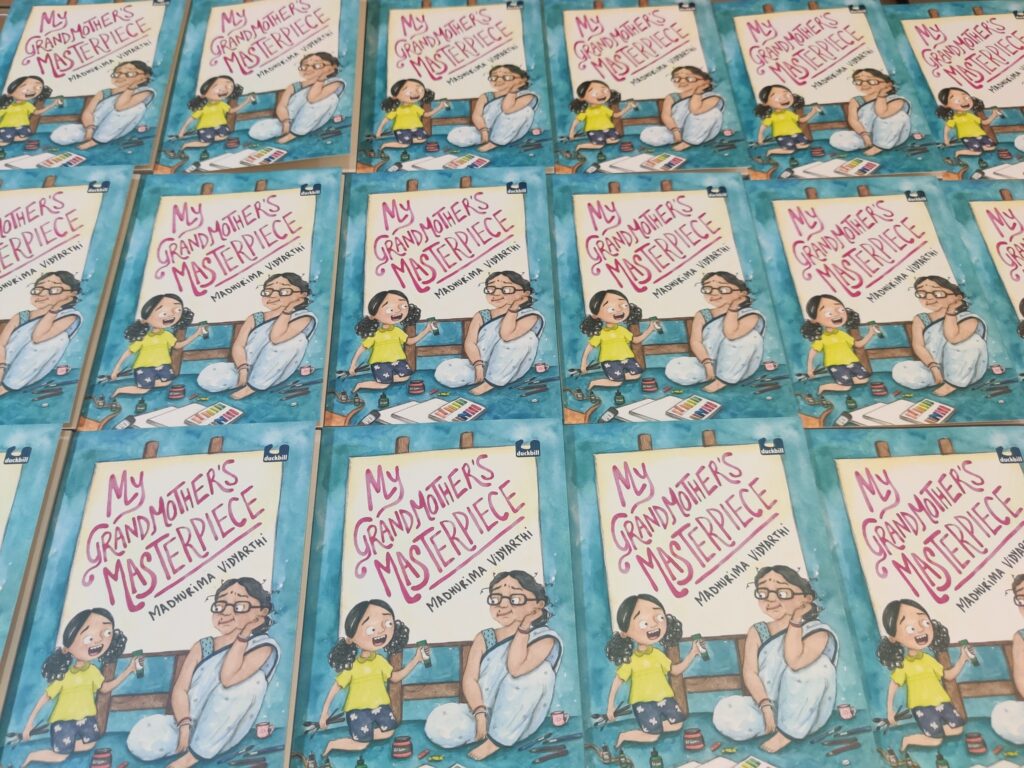

FII: Your previous ‘My Grandmother’s Masterpiece‘ subtly wrestled with feminist ideas and politics and had a pivotal grandmother-granddaughter relationship. You repeat the latter part in ‘Munni Monster’ as well. Could you describe what your relationship with your grandmother was like and if your bonding with her is an obvious source of inspiration to write these books?

Madhurima: The idea of the grandmother is [more] central to the first book than the second. In Munni Monster, she is used more as an accessory to facilitate the introduction of Munni’s character. In My Grandmother’s Masterpiece, the plot revolves totally around the grandmother and the issues are a little different.

My dadi died before I was born, sadly, but I was fortunate to have my nani till well into adulthood. They were both very strong women, with diverse interests outside their domestic duties. The character of Minima was based loosely on my mother-in-law who went back to art at a very late age, and although she hasn’t sold any paintings or become famous, it does give her a lot of pleasure.

Also Read: “Weaving Tales”: Women Behind India’s Literary Landscape Take The Foreground

FII: In the Afterword of your latest, you note how this book’s titular character is based on your aunt-by-marriage. Could you describe her, and your relationship with her?

Madhurima: The character of Munni Monster is almost exactly true to life. It took me, as I have said in the Afterword, some time to understand her as a person. It is not the same as simply dealing with a patient. Her main problem is what in medical terms is called ‘dysarthria’, which makes it difficult to pronounce the words she wants. This hampers communication to some extent, but it has got much easier over the years. Like all of us, she has her likes, dislikes, and moods. She’s in her early 70s, super intelligent and with a great zest for life.

Had she not been part of our family I would not have been able to write the story in the way I did. We live in the same family home, so her quirks and characteristics have been very easy to document — that has been a great advantage.

FII: As for most things in India, there isn’t any sensitive language for pressing issues. And especially because this book is written for younger readers (age 9+), were you concerned about how you’re going to navigate that terrain? Additionally, were you, through this book, invested in introducing a language about cerebral palsy and a talking point for parents/children? Books shouldn’t be burdened with this desire, but perhaps if that was the aim, please let us know.

Madhurima: My main concern, as with My Grandmother’s Masterpiece, was to sound natural and not preachy at all. I had to be cautious, of course, and not sound as if I wanted to impart a message, which I didn’t, by the way. Though we discuss a lot of issues at home, with the children and in their hearing, a book for general consumption has to be approached differently.

For any book I write, there is not really a deliberate choice of language or level of comprehension. I think about the book as a whole and what the story would need. A lot of deliberation also goes into who is telling the story — their POV and voice and their perspective on certain issues. With child characters, I am careful not to make them oblivious to their surroundings. I think children pick up much more than we give them credit for. They may react differently to adults depending on their age, but I think they notice almost everything that goes on around them.

My aim in writing Munni Monster was simply to tell a story. Nothing more, nothing less. Had I wanted to deliver a message, I wouldn’t have been able to write the book. Certain ploys were deliberate, such as putting the family under financial strain to highlight the issue of Munni’s medical insurance. But if this book throws light on this social injustice and gets people talking, then that, I would say, is an added advantage.

FII: I found Riya’s character endearing as well, though she does several mischievous things. I don’t really think she was introduced to satisfy the wealth-gap angle (between her and Mishti’s family), but she does help bring in contrast to kickstart so many conversations. How do you create this character and what role does she play according to you?

Madhurima: Riya, as you have rightly pointed out, is a catalyst for many things. Her main function in the story was to introduce the word ‘Monster‘. So, she had to be insensitive and brash and somewhat arrogant. At the same time, she had to be relatable, and realistic, someone we could possibly meet in school. The bullies we meet in school are the same ones who grow up to be bullies in the workplace, so they are important characters in my stories.

Also Read: FII Interviews: Ikroop Sandhu — Author Of “Inquilab Zindabad”

FII: I also loved how caregiving, grief, humour, working women, and money are as central to this narrative as the aim to discuss disability and love. How difficult (or easy) was it for you to weave these potentially loaded topics into the narrative in a dialogic manner because they must appear effortless and not enforced?

Madhurima: It was difficult, again, to discuss these problems without appearing to preach. Difficult to show more than to tell and let the readers draw their own conclusions or start their own conversations. A common misconception is that children should be shielded from money worries. My take is that they should be given at least a general idea of what is going on (in case there is a crisis).

A realistic picture, because otherwise, they will blow the problem out of proportion in their own minds. So, the conversation about money should start young, in small insidious ways, perhaps with pocket money or taking children along while shopping for essentials. Introducing them to living costs, electric bills, concepts about budgeting, Etc. They do learn some basic accounting concepts in school so why not build on those?

FII: Could you share what you are working on next?

Madhurima: Too many things. But mainly a ghost story which is a full-length middle-grade novel and research for some historical fiction (also middle-grade) that is around a person I grew up admiring. Also, a contemporary novel for adults, which is nearing completion.

The interview has been paraphrased and condensed for clarity, at the interviewer’s discretion.