Hamida Banu’s story remains primarily shrouded in mystery. With hardly any official record of her remarkable feats, it is deplorable that a woman’s achievement both inside and outside of the sports arena remains unacknowledged and uncelebrated. As the first of her kind, Banu’s entry into the sphere of wrestling is not only a valuable sports accomplishment but also a significant social change as she defies oppressive gender and religious structures.

It is mostly through newspaper clips of the 1950s that any light can be shed on Hamida Banu’s life as a sportswoman. The ignorance around her life is suggestive of a mentality that is still reluctant to accept women wrestlers or accord them with much importance. In contemporary imagination, she is an almost mythical and mysterious figure: unbeatable, unfeminine, and even dehumanised.

Any attempt to find details about her personal life only leads to assertions of her wrestling prowess and eating capability: with claims like “she sleeps nine hours a day, trains another six and spends the rest of her time eating.”

Known as the “Amazon of Aligarh,” Hamida Banu’s life is mostly seen through a fantasised lens thus obscuring realistic details about her social position, struggles as a woman, and aspects outside her wrestling career. This is another reason why she is not often associated with modern-day women wrestlers as she is not presented as real enough.

In contemporary imagination, she is an almost mythical and mysterious figure: unbeatable, unfeminine, and even dehumanised.

However, The Paperclip attempts to archive her missing history through these fragmented news clips to formulate an interesting story of her life. Even though the focus is still largely on her wrestling career and almost superhuman might, the detailed descriptions of her legendary fights give a credible shape to the woman.

Entering the male-dominated field of wrestling

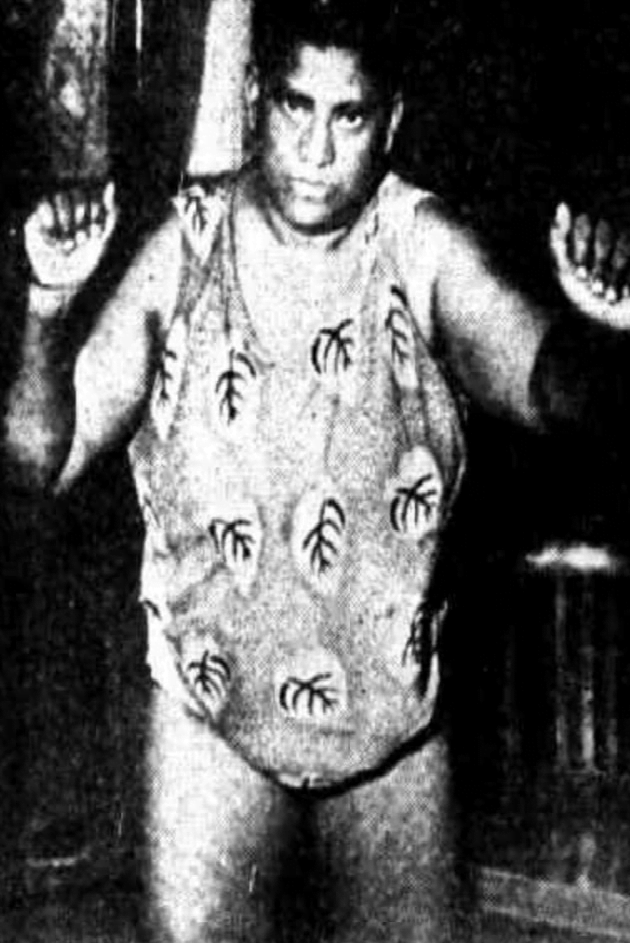

Hamida Banu’s journey to becoming an established female wrestler was often obstructed by patriarchal views which could not fathom a woman in the wrestling arena. Wrestling at a time when women’s participation in sports was highly limited and restricted, Hamida Banu competed with mostly male wrestlers. This meant facing the biases and insults of her opponents who did not consider her worthy enough to fight.

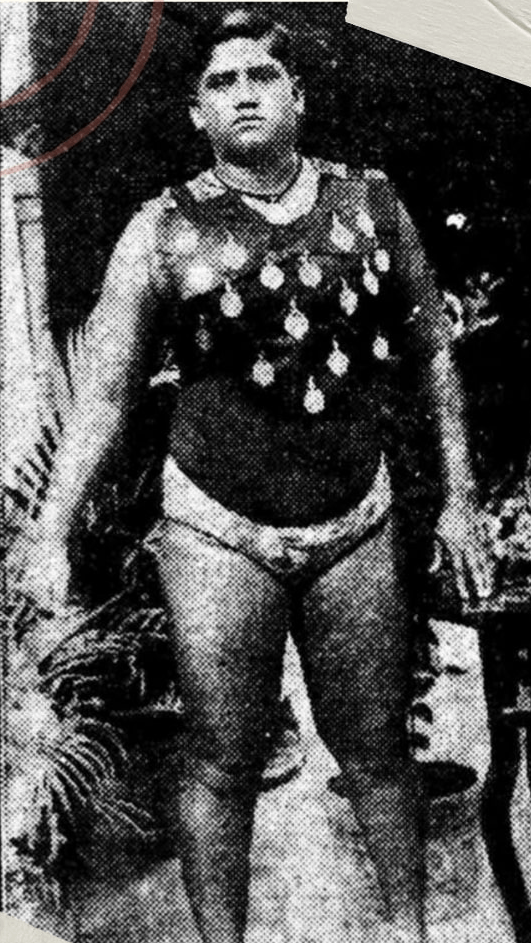

Belonging to a family of wrestlers in a small, conservative town, Banu chose to become a wrestler when such a category did not even exist in her society. Wrestling was considered a man’s sport as it carries with it the traditional manly qualities: force, aggression, competitiveness, and physical power. It was also considered indecent for women to enter this space as women are often sexualised in performing any sort of physical activity.

This was the reason that Banu’s competitors often ridiculed her attempts at wrestling, while simultaneously sexualising her as a marriageable entity. In a notable episode, Banu is challenged by an egoist male wrestler, Baba Pahelwan, to either marry him or defeat him in a wrestling match.

The rejection of Banu did not just arise from the conventional notions about female morality but also indicated a fragile patriarchal attitude which could not digest a woman wrestling better than men. However, Banu’s zeal was commendable as she continued on her wrestling journey, despite many such societal suppressions.

This already betrays a sensibility of male entitlement and misogynist outlook as he still posited Banu as a woman to be courted and not respected as a fellow athlete. His arrogance was further appalling as he was ignorant of the fact that Hamida had already ousted two other such suitors/competitors. The episode ends with an outstanding victory of Hamida as she overcomes Pahelwan in just 1 minute and 34 seconds!

In another incident, Hamida Banu’s skill was validated again as she crushed another overproud male opponent, Feroze Khan. He, too, met Hamida’s challenge with light-hearted dismissal and derision but was eventually humbled by a defeat at her hands.

However, her victories within the sports arena contrasted with her struggles outside. It was difficult for an orthodox community to accept her wrestling ventures. She was ultimately forced to leave Punjab and its wrestling community due to public insults and even physical assaults. During a bout in Kolhapur, Maharashtra, the audience threw stones at her and berated her for defeating her male opponent. In another event in Pune, Banu’s match was cancelled due to intervention by the controlling authorities.

The rejection of Banu did not just arise from the conventional notions about female morality but also indicated a fragile patriarchal attitude which could not digest a woman wrestling better than men. However, Banu’s zeal was commendable as she continued on her wrestling journey, despite many such societal suppressions.

Hamida Banu’s spectacular victory record contains an invincible winning of all her 320 bouts. Moreover, she tried to expand her horizons to take up international challenges by competing with European wrestlers. An article in Indian Daily Mail briefly records Banu being challenged by Raja Lai La, a woman wrestler from Singapore. She also defeated Vera Chistilin of Russia in less than a minute at a freestyle competition held in Bombay.

The brief records that are available on Hamida Banu testify to her resilience as undeterred by patriarchal discriminations and prejudices, she left her mark on the national and international wrestling environment of the 1950s.

Also Read: Mehrunnisa Dalwai: An Unsung Muslim Activist | #IndianWomenInHistory

Coming out of the ‘purdah‘

Hamida Banu was hounded by conservative religious injunctions to limit herself within the ‘purdah.’ The sporting attire donned by her was seen as breaking the norms of chastity and propriety. This attitude marks the objectification of women who cannot exist as athletes and are always put under the scrutiny of the male gaze. It is a regressive moral view that links women’s virtue with covering up their bodies.

Hamida Banu did not just resist the literal impositions of ‘purdah,’ but also other societal rules which limit a woman’s agency and movement. Her advent into the public sphere and not conforming to the gender roles established for women is a bigger subversion of women’s subordinated position. She did not just challenge those male wrestlers in the arena; it was a challenge against the whole patriarchal system which does not allow women to exist in supposedly masculine domains of sports, outward movements, and physical valour.

Hamida Banu did not just resist the literal impositions of ‘purdah,’ but also other societal rules which limit a woman’s agency and movement. Her advent into the public sphere and not conforming to the gender roles established for women is a bigger subversion of women’s subordinated position.

The legend surrounding her supposed vow to marry the person who will defeat her indicates Banu’s faith in her wrestling skills. It shows a woman who derives her self-worth from her abilities as a sportsperson and not superfluous patriarchal values. And, at the same time, this also helps her to perpetuate a ruse of presenting herself as a prize in the wrestling matches to convince her male opponents to compete with her.

Even though there is not much documented about her personal life, it would be erroneous to assume that she succumbed to traditional frameworks. There is a hint that she spent the years after retiring from her wrestling career organising dangals (wrestling bouts). This makes it apparent that Banu was not ready to let her legacy go to waste. She continued to inspire others to take up this profession.

Banu’s contemporary importance

There is now widespread recognition and appreciation of women wrestlers. The popular film, Dangal, depicted the biography of the Phogat sisters, where Geeta Phogat is the first woman wrestler in India to qualify for the Olympics. Phogat sisters are also celebrated for their wins at the 2010 Commonwealth Games. Geeta Phogat talks about defying gender roles and bringing positive change in her community through her wrestling advent.

However, the foundation stone to pave the way for women wrestlers was put by Hamida Banu. Though she is seen as almost a mythic figure, these admirable contributions by modern-day women wrestlers are a part of Banu’s legacy. Women’s wrestling was not recognised in the Olympics until 2004 which makes Banu’s victories in the 1950s even more remarkable.

She pioneered the women’s movement into the otherwise male-dominated sphere of wrestling and created a precedent for all the women who follow her. She is, ultimately, an integral part of women’s sports history — motivating women with her athletic skills and feminist potential alike.