Communalism has always been a significant social issue in India. In popular discourse, it is always perceived as an unhealthy attachment to one’s own religion which strongly emphasises the essential unity of the community against other communities. In colonial as well as post-colonial India’s stiff competition for power among identity and ethnic-based groups, communal violence has always proved to be an effective weapon through which society has always been made polarised to reap the political and electoral gain. Academically, the emergence of communal identities has been the subject t of intense debate and has been always understood through the prism of the Hindu-Muslim binary.

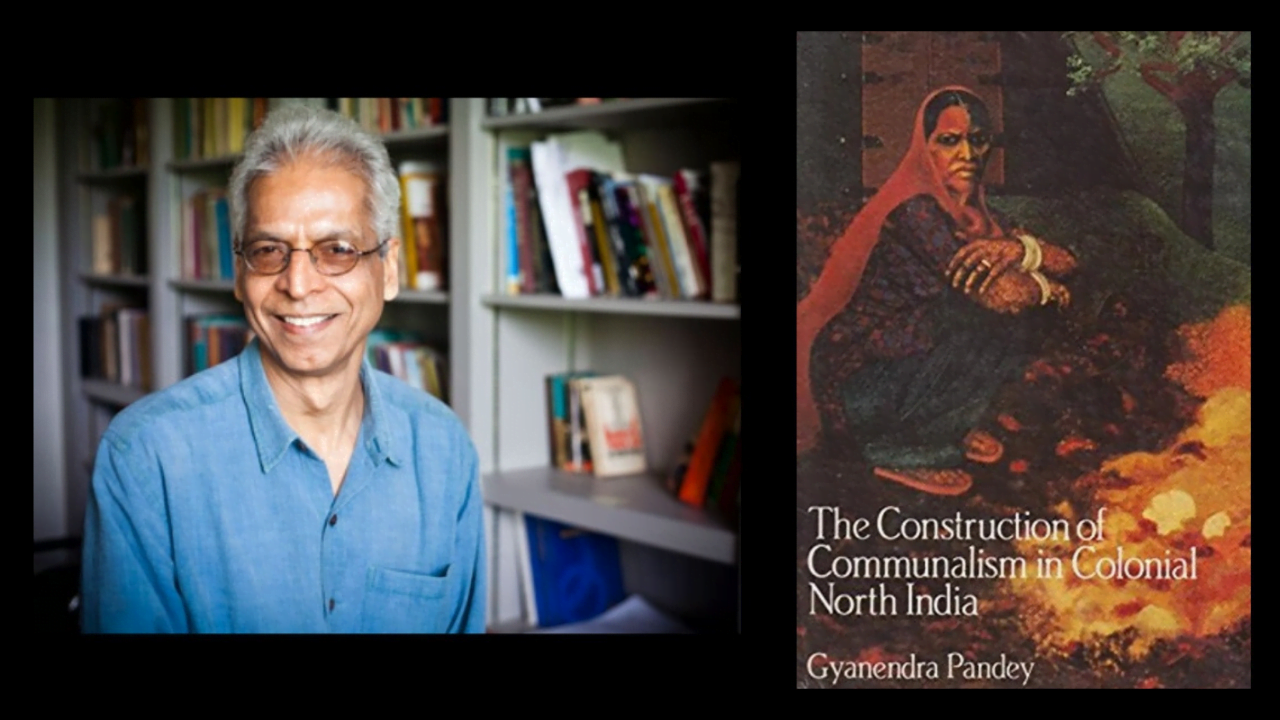

Despite being the central point of academic debate and popular rhetoric, the history of communalism remains inadequately researched and has been often intermingled with popular perceptions and propositions. In the context of these ongoing intellectually debilitating absurd assumption, Gyanendra Pandey’s ‘The construction of communalism in colonial North India’ offers a new understanding of the construction of Indian society and politics in the last two century and unfold different dimensions of communalism, nationalism and colonialism. This book rehearses some of the major issues and basic questions of Indian society with a sustained critique which has been described as the national question from the nineteenth century to recent times.

The book seeks to understand how communal identities were formed and mobilised in the context of British colonialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Pandey argues that communal identities were not inherent or pre-existing in Indian society, but were largely a product of British colonial policies. He traces the root of communalism to the British Policy of divide and rule, which sought to create divisions between different religious and ethnic groups in order to maintain control over India.

Communalism was not a monolithic or static phenomenon but was constructed through multiple processes that include the articulation of communal identities, the formation of communal organisations and the mobilisation of these identities for political purposes. He shows how the colonialist construction of Indian history has manifested religious bigotry and conflict as a distinctive feature of Indian society.

In this book, Gyanendra Pandey critiques the colonial historiography that reduced communal identities to ancient, immutable and irrational conflicts between religious groups. Instead, he proposes a new approach that examines the historical memory and accounts of the ‘little community‘, and highlights the ways in which communal identities are constructed and reconstructed over time.

In this book, Gyanendra Pandey critiques the colonial historiography that reduced communal identities to ancient, immutable and irrational conflicts between religious groups. Instead, he proposes a new approach that examines the historical memory and accounts of the ‘little community‘, and highlights the ways in which communal identities are constructed and reconstructed over time. One example of this approach can be seen in Pandey’s examination of Waqeat-o-Hades, a local community in Qasba Mubarakpur, which he uses to illustrate how communal identities are shaped by local histories and narratives.

However, it is important to note that Pandey’s approach is not limited to a particular time and space. Rather, it emphasises the contingency and complexity of communal identities, and how they are shaped by larger social, economic, and political forces. By focusing on the historical memory and accounts of ‘little communities‘, Pandey’s work challenges us to move beyond simplistic and reductionist understandings of communalism, and to engage in a deeper analysis of the complex and multifaceted nature of communal identities.

One of the strengths of the book is its rich theoretical framework. Pandey draws on the work of theorists such as Michel Foucault and Edward Said to develop a nuanced understanding of the ways in which colonialism and nationalism intersected to produce communal identities in India. His analysis is also grounded in extensive archival research and draws on various sources, including newspapers, government reports and personal diaries.

Pandey provides detailed case studies of communal violence in specific regions of North India such as Mubarakpur, Shahabad and Banaras which shows how the conflict between different religious groups was often sparked by economic and political competition rather than religious difference and communalism was not a uniform phenomenon. It was not limited to Hindus and Muslims but also existed among other religious and caste communities such as Sikhs, Christians and Dalits.

Also Read: Funny Boy: A Search Exploring Identity, Sexuality And Politics

The book provides an important insight into the ways in which British colonial policies contributed to the growth of communalism in colonial North India. One of the key ways in which colonial policies contributed to the growth of communalism was through land revenue policies that were based on individual ownership of land, which led to the marginalisation of Muslim weavers(Julaha) who were heavily dependent on the traditional system of collective ownership of land.

In major centres of cloth production such as Lucknow and Banaras, or Mau and Mubarakpur, the weavers and spinners faced violent fluctuations in the condition of their trade in the immediate pre-colonial as well as the early colonial period. The beneficiaries of the new condition in the cloth trade included, prominently, a large group of Hindu merchants and moneylenders who came to attain a perhaps unprecedented hold not only on the trade but on the weavers themselves.

The book also provides a detailed analysis of the political organisation and the movements that emerged in northern India during the colonial period and the ways in which they mobilised communal sentiments to further their own interests. The author examines the various political organisation and movements that emerged during this period, including the Hindu-Mahasabha and the Muslim League and shows how they exploited communal tension for political gain.

The heightened strength of merchants/moneylenders, their powerful position under the new colonial dispensation, and their increasing arrogance as the lower classes often saw it caused much annoyance to the ‘losers’- not only to lower classes like the weavers but also to the declining class of small zamindars and service gentry who claimed a ‘traditional’ authority and status. The weaver/moneylender(or weaver-merchant) conflicts inevitably followed, and since the weavers were mainly Muslims and the moneylenders mainly Hindus, this took the form of Hindu-Muslim strife.

The book also provides a detailed analysis of the political organisation and the movements that emerged in northern India during the colonial period and the ways in which they mobilised communal sentiments to further their own interests. The author examines the various political organisation and movements that emerged during this period, including the Hindu-Mahasabha and the Muslim League and shows how they exploited communal tension for political gain. These movements transform the very sense of community and redefine it to a larger extent. It makes communities historically more self-conscious and very much aware of the differences between themselves and others, the distinction between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’.

The author also highlights the diversity of subaltern experiences and the complexity of their identities. He argues that subaltern identities were shaped by a range of factors including caste, region, religion and occupation. For example, he shows how the relationship between caste and communal identity was not straightforward, and how subalterns often navigated multiple identities simultaneously.

While the book is an important contribution to our understanding of the origins of communalism in India, it has certain limitations in its analysis. It focuses too narrowly on the role of colonialism in the construction of communal identities. While it is true that British policies of divide and rule played a significant role in exacerbating communal tensions in India, other factors such as social, economic, and cultural factors were also important in the formation of communal identities.

Pandey’s theory of communalism in Northern India is still relevant today as communal tensions and violence continue to plague the region. But his theory needs to be re-evaluated and updated in light of changing social and political contexts. His theory needs to be updated in the context of the increasing role of the state in fomenting communal tensions. The rise of Hindu nationalism in India has led to the instrumentalisation of communal identity for political gain, with the state using communal rhetoric and policies to mobilise support and consolidate power.

His theory also tends to generalise the experience of communalism in northern India without paying attention to regional variations and differences. This overlooks the diversity of experiences and responses to communalism across different regions and communities.

However, his theory of communalism in Northern India is still relevant today as communal tensions and violence continue to plague the region. But his theory needs to be re-evaluated and updated in light of changing social and political contexts. His theory needs to be updated in the context of the increasing role of the state in fomenting communal tensions. The rise of Hindu nationalism in India has led to the instrumentalisation of communal identity for political gain, with the state using communal rhetoric and policies to mobilise support and consolidate power.

Also Read: Book Review | RSS: The Long And The Short Of It By Devanura Mahadeva

Despite its various limitations, this book remains an influential contribution to the ongoing debates surrounding communalism in South Asia. Its emphasis on the constructed nature of communal identities and the agency of individuals and communities provides a valuable framework for understanding this complex and multifaceted phenomenon.

About the author(s)

Aamir Raza is a dedicated researcher based in New Delhi, India. He holds a Master's degree in Political Science from Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi. He has been previously associated with Lokniti-CSDS and the Institute of Perception Studies as a Researcher. His areas of research interest include Electoral politics, representation, minority studies, ethnic politics and democratisation.