Sughra Begum was a renowned social reformer, an activist and an Urdu writer who devoted her life towards furthering women’s causes such as their education, their rights and relaxation of the purdah system that restricted Muslim women from participating in the public sphere. She was an active part of several women’s associations and clubs that played a significant part in defining women’s roles in the new India. She also contributed to the nationalist cause through her writings on the importance of communal harmony and the need to use Swadeshi goods.

Being a Hyderabadi Urdu writer who was also a woman, Sughra and her writings have been allocated a disproportionately small space in history as opposed to the immense social change she brought about in pre-colonial Hyderabad.

Early beginnings of Sughra Begum

Begum Sughra Humayun Mirza was born in 1884 when the Princely State of Hyderabad was under the reign of Nizam Asaf Jahi VI. Her father, Dr Haji Safdar Ali Mirza, was a respected surgeon who had migrated to Hyderabad to serve the Nizam’s Army during the rule of Asaf Jahi II. Her mother Maria Begum was a woman of literary merit in her own right, being a famous scholar of Arabic and Persian.

Although unable to acquire a formal education because of the restrictions placed on Muslim women at the time, she was home-schooled in Urdu and Persian. She married the renowned barrister Humayun Mirza at the tender age of 16.

Social Reform and activism

People like Haji Safdar Ali Mirza who lived in Hyderabad but who were socioculturally rooted elsewhere came to be known as ghaer-mulkis or non-countrymen. Because they were denied equal status by the traditional elites of Hyderabad, the ghaer-mulkhis emphasised the importance of a sound education and personal achievement rather than the privileges of birth. The contribution of ghaer-mulkhi men and women in the education of young women as well as the relaxation of the purdah norms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is quite remarkable.

Pardah clubs and women’s associations in the early 20th century were considered safe spaces for women to come together and interact freely with their peers while adhering to the purdah norms. Sughra Begum and her contemporary Tayyaba Begum were prominent Hyderabadi women involved in several such associations and clubs such as the Hyderabad Ladies’ Association, the Anjuman-e-Khawateen-e-Islam and the Lady Barton Club.

Sughra Begum herself would go on to establish the Anjuman-e-Khawateen-e-Deccan (Deccan Ladies’ Association) in 1919. These became forums for debating matters relating to girls’ education, for fund-raising for girls’ education, and for arranging sporting facilities for women while also furthering the organisational skills of its members.

Begum Sughra established the Madrasa-e-Safdaria in 1934 using a portion of her own property with the singular objective of educating young Muslim girls in their mother tongue, Urdu. Named after her father Safdar Ali Mirza, the school exists to this day in Humayun Nagar. Safdaria, which had started off 88 years ago with only seven young girls as pupils, has since then swelled in number and now is home to around 1000 students.

Begum Sughra and her life in words

Sughra Begum was a well-known writer who traversed both genre and medium through her work. She wrote poetry under the pseudonym Haya and also authored several novels, essays and travelogues. Having written 14 novels, she is believed to be Hyderabad’s first female novelist. Her novels were meant to be inspirational stories to its women readers, their primary goal being to affect social change. Her 1929 novel Mohini for instance, is the aspirational story of a princess who relinquishes her inheritance and sets forth on a quest in search of Truth.

A significant episode in the novel is when the titular character discusses contentious subjects such as divorce and remarriage with the leading reformers of the day. Thus, Sughra Begum’s fiction too was heavily informed by her role as a social reformer and activist.

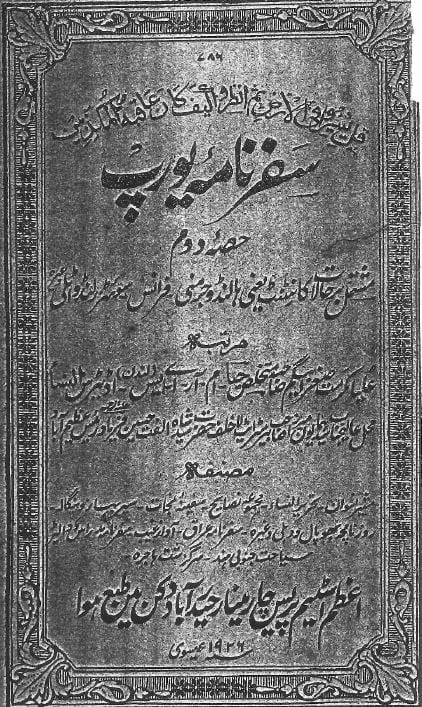

She wrote five travelogues between 1910 and 1920 while travelling through Europe, Asia and pre-partition India. These were accounts of the different places she visited, ranging from museums to hospitals, interspersed with bits of her personal life. As these tracts were serialised in her journal An-nisa, they became a window into the wider world for the pardah-nashin reader. Her travelogues are unique for their exhaustive attention to detail. In one of her accounts written while visiting Berlin, she articulates:

“I was exhausted … [But] tired or not, write I must. The anxiety to write hounds me in such a manner that I cannot see anything without worrying about writing. I see things, I write them down then and there. Then I note it all down in my diary when I return home.”

From these notes in her diaries, she later fleshed out her travelogues. Through this meticulous attempt at documenting her experiences in the public sphere, Sughra Begum reworks the idea of the ‘traveller,’ typically a European man. Her writings allowed her readers to visit (or perhaps revisit) the triumphs and tribulations of travel through the eyes of a Muslim woman.

An-Nisa was an Urdu language monthly women’s journal published in Hyderabad starting from 1919 to 1927. Begum Sughra was both editor and contributor to the enterprise. Sughra herself wrote several of the articles for the journal while also encouraging other women to write. Most of the articles were by women, though some were written by men who championed women’s causes.

The journal published creative pieces, social and literary essays and articles on housekeeping, nursing, women’s health and education. The popularity of An-nisa spawned several other Urdu periodicals by and for women like Khadeema (1922), the illustrated Hamjoli (1931 – 1940), the illustrated Safina- e-Niswan (1932), Naheed (1938), Iram (1940), Khayabaan-e-Dakkan (1941), Hairat (1947) and Iqdaam (1950).

The Zeb-un-nisa was another journal edited by Begum Sughra from 1934 to the 1940s in Lahore. The name of the journal translates to beautiful woman and is a possible hat-tip to the Mughal Princess Zeb-un-Nissa — an extremely learned scholar and poet in her own time.

The Zeb-un-nissa benefited from the advantage of having a better support system including a joint editor to assist Sughra and a far superior printing and publishing arrangement to the An-nisa. The Zeb-un-nisa featured pieces similar to those published in its predecessor — short stories, poetry, Begum Sughra’s travelogues and embroidery — but in addition to these, it also featured pieces that were decidedly more radical. There were now essays that debated highly contested social issues such as women’s suffrage, their education and rights.

The periodical also covered the meetings of the All India Women’s Conference and the Women’s Muslim League in the 1930s. All in all, Sughra’s new publication was of a far more political turn than the An-nisa.

Urdu women’s magazines like the An-nisa and the Zeb-un-nisa are among the few written accounts that record the everyday lives of middle-class Muslim women in purdah. As printing became cheaper and literacy was encouraged, these periodicals became an inexpensive and efficient medium through which women could communicate and express their views outside the domestic domain.

Unfortunately, an attribute synonymous with such women’s periodicals is their almost non-existence in the annals of history. While most libraries and museums preserve magazines and newspapers, they rarely save women’s journals.

Women’s periodicals are also largely absent from standard histories of Urdu literature and journalism. It is now, close to a century after their publication, that scholars like Nazia Akhtar and Gail Minault have come forward to fill in the gaps left by our hegemonic understanding of history.

About the author(s)

Keerthana (she/her) is a third-year English Literature student at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi University. She is interested in analysing art and pop culture through feminist and other sociocultural theories. She enjoys literature, music, films and the occasional cricket match.