Anomalies in climate, long theorised and forewarned about, are now finally becoming a harsh reality, urging those of us who have been hitherto dismissive of the looming threat of climate change to finally begin to acknowledge the sheer scope of damage it can wreak.

In India, several states continue to grapple with intense rainfall; videos of landslides in the tourist destinations dotting Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand have gone viral on social media, with rescue operations underway to assist locals and trapped tourists, and the nation’s capital came to a standstill only days ago while traffic was halted and alarm bells rang for a possible flood situation as the waters of the river Yamuna breached its danger mark. Nearly thousands of people who lived in low-lying areas near the river were rescued and rehabilitated in shelters ranging from schools to community centres.

There is a growing need to identify and devise measures to expeditiously deal with climate change, yet existing scholarship on ecological activism offers a very stunted perspective on the scope of the movement.

For example, ecological activists often tend to evoke images of heterosexual institutions such as marriage and the nuclear family to arouse feelings of concern within the populace. In other words, activists tend to arouse sympathy for their cause by appealing to conservative sentiments- we are told the only reason we must care for the environment is to protect our children and our families.

Criticisms against dominant strands of eco-activism include its tendency to essentialise gender- ideas such as love for the environment and fostering loving relationships with nature are funnelled into existing gendered paradigms; women are often viewed as being particularly devoted to the cause for ecological advocacy by virtue of their reproductive labour.

For example, in Maria Mies’ 2015 essay titled ‘Mother Earth,’ published in Hawley’s ‘Why Women Will Save the Earth,’ the author says, ‘Women, mothers, were among the first to recognise [climate change] because they ask: What future will our children have in such a world.’ There is a need to centre feminist perspectives in the fight to save the environment, especially in the realm of reproductive justice.

Studies offer valuable insight into how climate change worsens reproductive health. In Bangladesh, a report revealed the plight of women living in coastal regions susceptible to natural disasters intensified by climate change. Rising sea levels and cyclonic storms lead to an increase in salinity in the rivers and lakes, which causes several reproductive health issues such as hypertension and preeclampsia in pregnant women, and reproductive tract infections.

Similar concerns were raised by women living in the Sunderbans, where water bodies from which water is consumed were revealed to have abnormally high levels of salinity.

Access to abortion also takes a hit during disasters. In India, where the stigma surrounding abortion already significantly worsens the ability of pregnant people to access medical termination of their pregnancies, disasters only serve to cut them off from reproductive healthcare completely. It is already acknowledged that India’s model of abortion, although recently expanded in scope at the behest of Supreme Court judgements, continues to be restrictive and inaccessible for most.

Women often seek hysterectomies to remedy the reproductive disorders this may cause, yet access to such healthcare is rare. For most women, the impact of climate change on their bodies is further filtered through layers of other sociopolitical conditions- those in rural areas are less likely to even receive a professional diagnosis.

Worse, the damage to connectivity wreaked by natural disasters effectively ensures that women in affected regions must arrange for long hours of inconvenient and often dangerous travel to even reach a health centre where they can seek help. It does not help that the distribution of relief material amongst survivors is hardly equitable; it has been demonstrated that women tend to end up with short sticks when it comes to rescue and relief operations as well.

Access to abortion also takes a hit during disasters. In India, where the stigma surrounding abortion already significantly worsens the ability of pregnant people to access medical termination of their pregnancies, disasters only serve to cut them off from reproductive healthcare completely. It is already acknowledged that India’s model of abortion, although recently expanded in scope at the behest of Supreme Court judgements, continues to be restrictive and inaccessible for most.

Public transit is flimsy at best; entire networks of connectivity often fall apart during times of crises owing to poor maintenance. Research focused on Mozambique and Bangladesh found that access to contraception and abortion is directly affected by climate change, and sees a downward spike both before and after a natural disaster is expected to occur. Miscarriage, early labour, congenital birth defects and other pregnancy-related complications are more common in areas most prone to the effects of climate change.

Menstrual health, too, is not left untouched by the looming threat of ecological disasters. In the aftermath of the deadly Super Cyclone Amphan, women taking refuge in emergency shelters plagued with unhygienic conditions would suffer from vaginal infections. They were made to stand in huge queues and resort to using polluted water in filthy restrooms shared with men. They would use unhygienic pieces of cloth as sanitary napkins for days at a time; there was no facility to obtain sanitary products or wash the cloth.

Relief operations often tend to relegate women’s sanitary requirements to the back, and women tend to not voice their needs with respect to menstrual health owing to the taboo surrounding the same. There exists a generally dismissive attitude towards menstrual health, especially during disaster management operations.

Erratic access to sanitary products aside, climate change-induced disasters often cause abrupt changes in menstrual patterns. The lack of appropriate healthcare to assist women in dealing with the same poses a huge challenge.

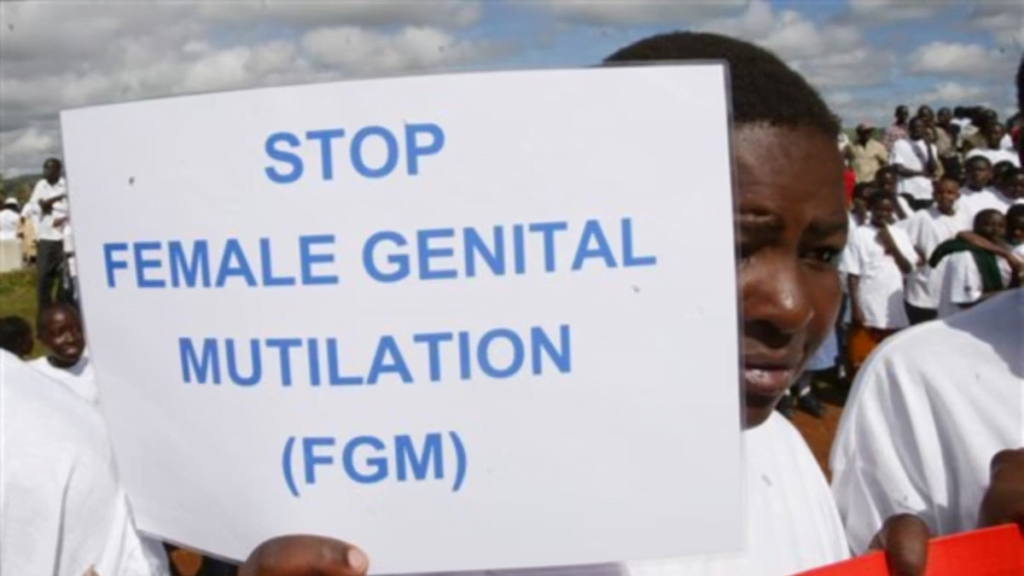

Although little research exists to examine the link between climate change and Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in South Asia, there is reasonable evidence to believe that environmental damages intensify factors linked to child marriage and FGM/C.

In the Horn of Africa, studies show that draughts caused by climate change led to an abrupt increase in child marriage and FGM/C in the region, with families essentially ‘marrying off girls to secure dowries, …to have one less mouth to feed, or… help the bride enter a better-off household.’ As the drought worsens in surrounding regions, girls are increasingly at risk of being married or becoming victims of the horrifying practice of FGM/C.

Further, intense and unsustainable climactic conditions are also driving out community workers who were involved in protecting girls from child marriages and FGM/C. In other words, worsening ecological conditions disproportionately affect young girls, putting them at risk of life-threatening operations and misogynistic practices.

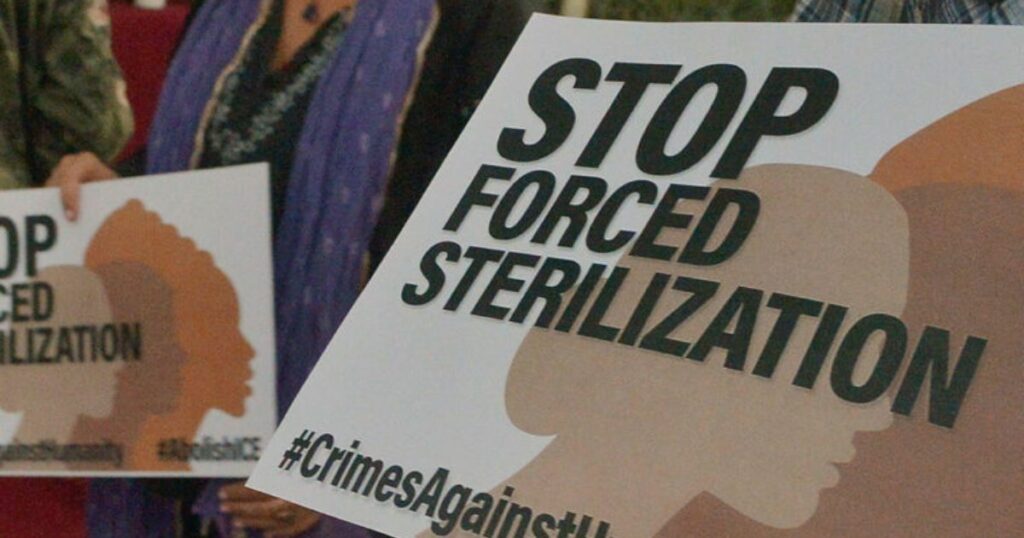

A true championing of the ecofeminist cause, however, would be incomplete without critically examining narratives concerning the mythical overpopulation phenomenon to combat climate change. In 2014, 15 women succumbed to death owing to mishandled sterilisation operations in Chhattisgarh. The women were reportedly offered a sum of 1400 Rupees to undergo the procedure.

The financial plight of women living in rural areas was effectively harnessed by the State to coerce sterilisation. Although officials insisted the procedure was entirely voluntary, the involvement of money in the program laid bare the transactional nature and the grim reality of the State’s goals.

Money acted as an operator of force; how can true consent be conceptualised when money is an incentive? The Chhattisgarh sterilisation drives are but a single part of India’s dark history of mass sterilisation drives.

Under the pretext of controlling population growth, governments since Indira Gandhi’s 1975 Emergency have utilised sterilisation as a political tool to disproportionately target marginalised communities, all the while hiding behind a façade of apparent environmental concern. At a time when indigenous communities increasingly become targets of displacement and suppression, it is important to dismiss any calls for population control as a way to advocate for the environment.

A growing body of research has now begun to examine the impact environmental degradation, global warming and climate change would have on sexual and reproductive rights. A common consensus amongst experts is that ever-worsening, unsustainable environmental conditions would impact the population differentially. Women would face the brunt of the same, and gender inequalities would especially deteriorate, particularly in regions most susceptible to erratic climate patterns such as India.

Although a relatively newer field of study, ecofeminist perspectives offer us enlightening revelations on the ways in which women and girls lie at a doubly disadvantaged position in light of climate-change-induced disasters by virtue of their oppression in society at the hands of men. For example, a recent study found a spike in domestic violence owing to climate change. Such research, while still at a budding stage, brings to light important concerns surrounding the future of sexual and reproductive health, and the feminist cause for women’s liberation, as the environment worsens and climate change wreaks havoc.

It is a rousing call to incorporate feminist perspectives into ecological advocacy and to ensure reproductive healthcare remains accessible during times of crisis.

About the author(s)

Mayank (he/him) is an 18-year-old student hailing from Delhi. He is particularly interested in offering cultural and literary critique through the lens of feminist and queer studies. In his free time, Mayank enjoys reading theory and is known to appreciate pictures of pet cats.