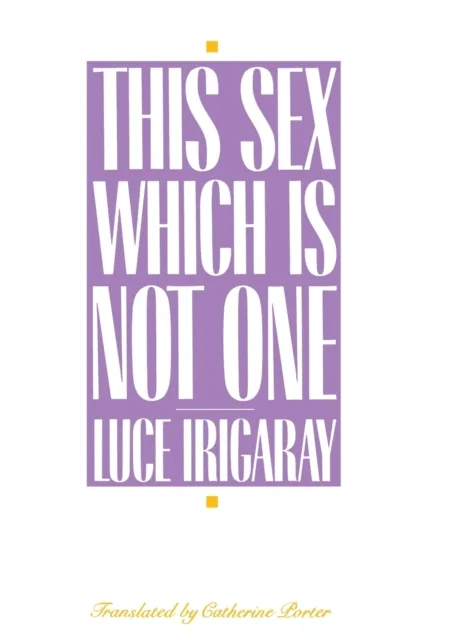

Luce Irigaray is a Belgian-born French feminist, philosopher, linguist, psychoanalyst and cultural theorist. Among her works is her second book This Sex Which Is Not One, published in 1977, which discusses psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s work and the political economy. In the eighth chapter of her book titled Women on the Market, Irigaray draws upon the work of Karl Marx and anthropologist Claude Levi Strauss to put forward a theory that expounds on the commodification and exchange of women in our society.

Irigaray claims that society, as we know it, is based on the exchange of women. Much like commodities that ensure the smooth economic functioning of society, the consumption, circulation and usage of women’s bodies ensures social and cultural life. As commodities women are at once utilitarian objects and also bearers of value, they have two forms, a physical or natural form and a value form.

And yet the exchange of women does not take place in terms of value that is intrinsic or immanent to them. Exchange can only take place when the two women are measured against a yardstick external to both of them. In Irigaray’s own words:

‘It is thus not as “women,” that they are exchanged, but as women to some common feature their current price in gold, or phalluses — and of which they would represent a plus or minus quantity.’

A woman’s value thus is always just out of reach; only to be felt during the operation of the exchange. Of course, the commodity (the woman) cannot exist in isolation — it exists only in relation to the two men who are involved in the market as active participants. The exchange of women and commodities is always connected back to men — when a man “buys,” a girl for instance, the father or the brother is paid and not the mother. Here, wives, daughters and sisters have value only because they carry the possibility of creating positive relations between men.

Irigaray claims that society, as we know it, is based on the exchange of women. Much like commodities that ensure the smooth economic functioning of society, the consumption, circulation and usage of women’s bodies ensures social and cultural life. As commodities women are at once utilitarian objects and also bearers of value, they have two forms, a physical or natural form and a value form.

In other words, the exchange of women between men helps to maintain what Irigaray calls a “masculine hom(m)o-sexuality,” the actual realisation of which is forbidden. In this context, heterosexuality becomes a mere alibi shrouding a man’s relations with himself or with other men. This hom(m)o-sexuality enforces a “sociocultural endogamy,” by virtue of which women are inevitably excluded from the social order.

Simply, men may make commerce of them but will not enter into commerce with them. Consequently, the commodity (a woman) is divided into two irreconcilable bodies — her natural body and her socially prized, exchangeable body, which represents a particularly mimetic expression of masculine values.

The commodification and exchange of women is what upholds the patriarchal status quo. Though women constitute a natural as well as social value in such a social order, their development occurs in the passage from one social role to the other.

Mothers are indispensable to the continuation of the social order as far as their maternal responsibilities such as child rearing or domestic maintenance are concerned. But their roles remain limited to maintaining the social order without intervening or changing it.

As a mother, a woman remains tied to re(productive) nature. Though man’s very social existence and sexuality are tied to the work of nature, their relationship to nature is denied so that relations among men may prevail. As a result, mothers are reduced to becoming a means of reproduction alone — instruments of procreation marked with the father’s name and confined within his house. The mother thus becomes part of the father’s private property, excluded from exchange.

The incest taboo essentially represents this refusal to permit productive nature (women) from becoming active participants in the economy of exchange. Mothers are indispensable to the continuation of the social order as far as their maternal responsibilities such as child rearing or domestic maintenance are concerned. But their roles remain limited to maintaining the social order without intervening or changing it.

The virginal woman, unlike the mother, does have exchange value. According to Irigaray: ‘She is nothing but the possibility, the place, the sign of relations among men. In and of herself, she does not exist: she is a simple envelope veiling what is really at stake in social exchange. In this sense, her natural body disappears into its representative function.’

The violation of a literal envelope accomplishes the metamorphosis from woman to mother — the hymen, which has come to symbolise the taboo of virginity. Once she is no longer a virgin, a woman is considered private property and as such no longer of value in the economy of exchange among men.

Another role imposed upon women in the social order is that of the prostitute. She is explicitly condemned and implicitly tolerated. In the case of the prostitute, the passage between usage and exchange becomes murkier. The qualities of a woman’s body are termed “useful,” but only because they have already been appropriated by a man. Among her “useful,” qualities is masking the locus of relations among men. In such a case, the woman’s body is of value because it has already been used; usage is not just potential anymore but has been actualised.

The glorification of reproduction and motherhood, ignorance and even a lack of interest in sexual pleasure, a passive acceptance of man’s “activity,” and seduction that arouses the consumers’ desire while receiving no pleasure in return are some of the features generally attributed to female sexuality.

Pre-ordained roles such as the mother, the virgin and the prostitute confine feminine sexuality within the bounds of what is socially acceptable in a patriarchal society. The glorification of reproduction and motherhood, ignorance and even a lack of interest in sexual pleasure, a passive acceptance of man’s “activity,” and seduction that arouses the consumers’ desire while receiving no pleasure in return are some of the features generally attributed to female sexuality.

Whether she is a mother, a virgin or even a prostitute, this social order denies her the right to her own pleasure. A woman’s lack of sexual desire or “rigidity,” is assumed to be inherent to her feminine nature. In reality, women’s perceived frigidity is less “natural,” and more a product of continued subjugation to the ideal of femininity imposed upon them by the patriarchal society that they inhabit.

The division of labour, specifically sexual labour, requires that women be objects of desire without ever having access to desire themselves. The economy of desire is a man’s world. Does this economy subject women to a schism — matter or medium of exchange? (re)productive nature or fabricated femininity? This schism is experienced by women without any possible benefit or compensation to be attained.

About the author(s)

Keerthana (she/her) is a third-year English Literature student at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi University. She is interested in analysing art and pop culture through feminist and other sociocultural theories. She enjoys literature, music, films and the occasional cricket match.