The phrase, ‘binary oppositions,’ popularised by notable semiotician Ferdinand de Saussure and now a crucial aspect of structuralist theory, refers to such entities that derive their meaning by determining themselves through another entity perceived to be opposite in meaning. For Saussure, and for a host of other postmodern philosophers, the relation between such units of language engaged in binary opposition is symbiotic and complementary instead of being contradictory.

For eminent Palestinian-American anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod, the opposition between the ‘Self,’ and the ‘Other,’ forms the foundation for Western anthropology. The ‘Self,’- here referring to the Western world that posits itself as self-evident and natural- derives its identity by demarcating the non-Western anthropological field of study as the ‘Other.’

Much of Lila Abu-Lughod’s works offer valuable insight into the role of culture in anthropology, how the global South is always studied from an imperialist gaze, and the ways in which one can analyse shifting power relations in society.

In her seminal essay, “Writing Against Culture,” (whose title seems to be a tongue-in-cheek reference to Clifford and Marcus’ collection “Writing Culture,”) Lila Abu-Lughod elaborates on the role of culture in anthropological research. According to her, culture operates as a framework to enforce separations that reflect a sense of hierarchy. Indeed, much of the essay focuses on the idea that the creation of a Western self in relation to the subjects of anthropological study relies on violent repression of any forms of differences that may exist in the West.

By homogenising the West and positioning it as exterior to the subjects they claim to study, anthropologists risk wading into what Lila Abu-Lughod defines as a ‘crisis of selfhood.’ She further refers to feminist theory to highlight the problematic aspects of the self-other division in anthropology.

Much of feminism, according to Lila Abu-Lughod, is devoted to helping women become selves, and thereby liberate them from being defined solely as the ‘Other,’ to men’s ‘Self.’ This, however, resulted in an acute crisis of selfhood, whereby it was difficult to reconcile the multitude of experiences of lesbians, Black women, women of colour and other marginalised women with those of women privileged in some sense or the other.

How could such a vast array of lived experiences be collimated into a single self? In their examination of the complexity of identity and intersectionality, feminist theory offers anthropology important lessons- first, that the self is never truly natural; it is always a construction defined in relation to another entity, and second, that to construct a self, entails the repression or ignorance of important forms of differences that could offer important insight into less-examined forms of power relations.

In particular, Lila Abu-Lughod concerned herself with examining the position of feminist anthropologists. She argues that feminists engaged in anthropology are uniquely positioned to confront the dubiousness of the belief that the relation between the self and the other is devoid of power. For her, the other is often defined in relation to a dominant self, and this relation is founded not just on differences but on inequality.

As such, the anthropological division of the Western self and the non-Western other (portrayed as exotic, barbaric and so on) is an expression of imperialist attitudes toward the global South. Even attempts to decolonise anthropological texts by giving voice to the other fall short of truly examining the vast scope of colonial power Western anthropologists wield. Similarly, male anthropologists delude people into thinking that they are ‘letting women speak,’ while in reality, they continue to hold exclusive control over academia and social life.

Lila Abu-Lughod further highlights the dismissal feminists face because their anthropological studies are deemed as only partial representations of society by their male counterparts. She argues that in fact, most studies are equally partial; indeed, most ethnographies often only focus on male members of a community.

Culture to her is the tool by which divisions between the self and the other are manifested in anthropology. Anthropologists tend to work from an assumption that Western culture is superior, or at least not worthy of the kind of debasing examination through the colonialist gaze that non-Western cultures are subjected to. She further enlists modes of writing that she sees as defiant ways to counter the essentialist and homogenising tendencies of culture in her field of work, which she also effectively utilises in her own ethnographies.

Lila Abu-Lughod particularly takes a cue from the Foucauldian conception of power, whereby power and discipline (through which power is imposed) are not just restrictive, but also, in some ways, productive. Power may inspire discourse and resistance. She utilises this idea for her ethnographic analysis of her experiences with the Bedouins.

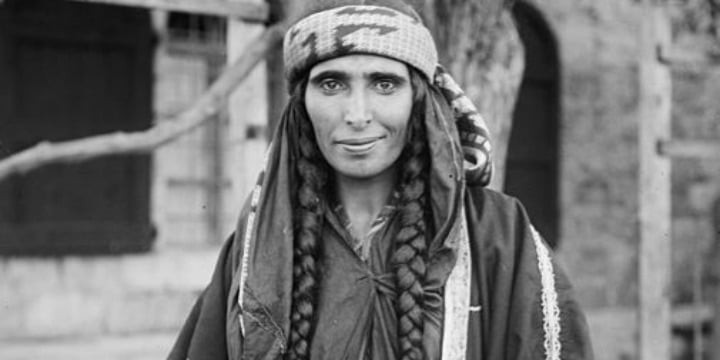

Lila Abu-Lughod’s research work during her time spent with the Awlad ’Ali Bedouin tribe in Egypt is hailed by students and professors of anthropology as a brilliant and enlightening ethnography. In a paper titled, “the romance of resistance,” she further proposes the idea of using resistance- not just big forms of revolt and protest- but smaller, non-organized forms of resistance through cultural means such as poems, songs and so on as a diagnostic of power, or, in other words, as a tool to examine the shifting terrains of power in society.

Lila Abu-Lughod particularly takes a cue from the Foucauldian conception of power, whereby power and discipline (through which power is imposed) are not just restrictive, but also, in some ways, productive. Power may inspire discourse and resistance. She utilises this idea for her ethnographic analysis of her experiences with the Bedouins.

Here, Lila Abu-Lughod examines the shift in attitudes and forms of small-scale rebellions amongst the Bedouin women against the system of male supremacy that inhibited their lives and physical movement especially, due to a redistribution of power in the region with increasing globalisation. During her first stay with the tribe, she briefly describes four forms of rebellion.

First, small defiant acts were carried out in the sexually-segregated women’s spaces wherein women would often plan and conduct secret trips to healers or visits to their kin, or smoke secretly until children in the household warned them of the arrival of their male family members. For Lila Abu-Lughod, such a form of resistance is in sync with Foucault’s proposal of power being productive- the Bedouin women embraced sexual segregation while carrying out defiant acts and fiercely protecting their exclusive spaces.

Second, Bedouin women would often protect young girls in their families by rejecting marriage proposals for them, either indirectly (in one instance, she describes the case of a woman who conveyed that a young girl in her family was already going to marry a cousin to shoot down a proposal by a family she didn’t deem appropriate) to direct rejections (although rarer, stories of women in the tribe rejecting the horrifying fate of arranged marriage fiercely captured the imagination of other Bedouin women.)

If the marriages did ultimately take place, women would often voice their discomfort using songs they would sing publicly at the ceremonies. These songs would take a dig at men by making taunts about their social status, wealth, age or beauty.

Third, Bedouin women would engage in what Lila Abu-Lughod terms as sexually irreverent discourse. They would make fun of men and manhood; in folktales they would portray male genitals as deficient or symbolizing the lack of a womb, thereby subverting phallocentric views. In stories Bedouin women would narrate and laugh about, male fears surrounding castration would also become the subject of humour.

Fourth, and perhaps most notably, Bedouin women would write and sing ghinnawas, usually in ordinary conversations. In these songs, they’d sing about sentiments of vulnerability and love, demonstrating emotions that talking about outside their spaces would generally be frowned upon. For example, poems talking about romantic love and vulnerability to others were considered dishonourable. Such forms of resistance offer a glimpse into the ways in which the lives of Bedouin women were restricted through ‘restriction on movement, elder kinsmen’s control over marriage, patrilateral parallel cousin marriage…’

However, upon returning to stay with the tribe in the late 1980s, Lila Abu-Lughod observed several differences and changes in attitudes and social norms. For instance, poetry had become an almost exclusively male forum for resistance, while women’s poetry was saved in the form of cassettes and dying out otherwise.

Lila Abu-Lughod attributes such a shift to the complete cementing of power of elder kinsmen in tribal communities. This was due to increased monetarisation and privatisation of property which gave patriarchs more economic power.

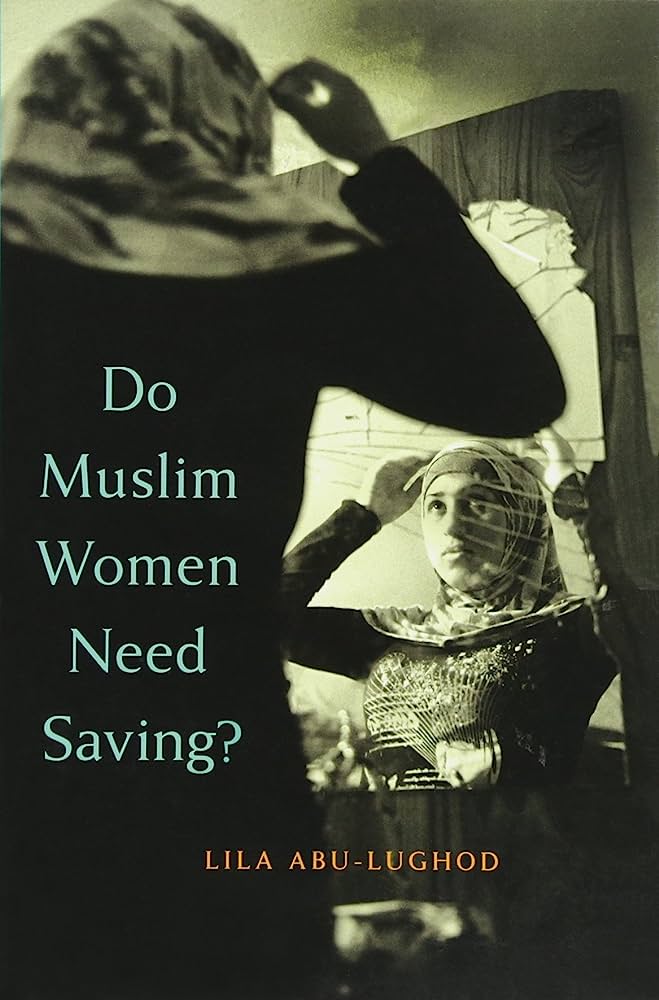

In her work, ‘Do Muslim Women Need Saving,’ she presents an anti-colonialist critique of the tendency of imperialists to wield women’s rights as a tool to rationalise militarist interventions. Indeed, she argues that such imperialist powers ignore the fact that by continuing their colonial projects, they further complicate the lives of women living in fundamentalist countries and create newer networks of restrictions on their movement and lives.

At the same time, this redistribution of power also gave rise to newer modes of resistance amongst Bedouin women. Younger women were increasingly resisting restrictions imposed on their physical movement. Often male kin would start slanderous accusations against them to disparage them; in such cases, women would unite to stave off these rumours. Clothing such as negligees and lingerie became popular amongst women, and even cosmetics such as moisturising creams were bought by them. This development in consumption patterns amongst women, according to the author, is reflective of the sexualization of femininity brought by a rise in consumerism and capitalism.

In her work, ‘Do Muslim Women Need Saving,’ Lila Abu-Lughod presents an anti-colonialist critique of the tendency of imperialists to wield women’s rights as a tool to rationalise militarist interventions. Indeed, she argues that such imperialist powers ignore the fact that by continuing their colonial projects, they further complicate the lives of women living in fundamentalist countries and create newer networks of restrictions on their movement and lives.

Lila Abu-Lughod’s works offer a fascinating insight into the relationship between power and protest. Currently a professor, Abu-Lughod’s works continue to be referenced in anthropology for their commentary on culture, power and gender.

About the author(s)

Mayank (he/him) is an 18-year-old student hailing from Delhi. He is particularly interested in offering cultural and literary critique through the lens of feminist and queer studies. In his free time, Mayank enjoys reading theory and is known to appreciate pictures of pet cats.