Trigger Warning: This is a review of the book ‘Of Captivity and Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India’ and mentions gender-based violence and rape.

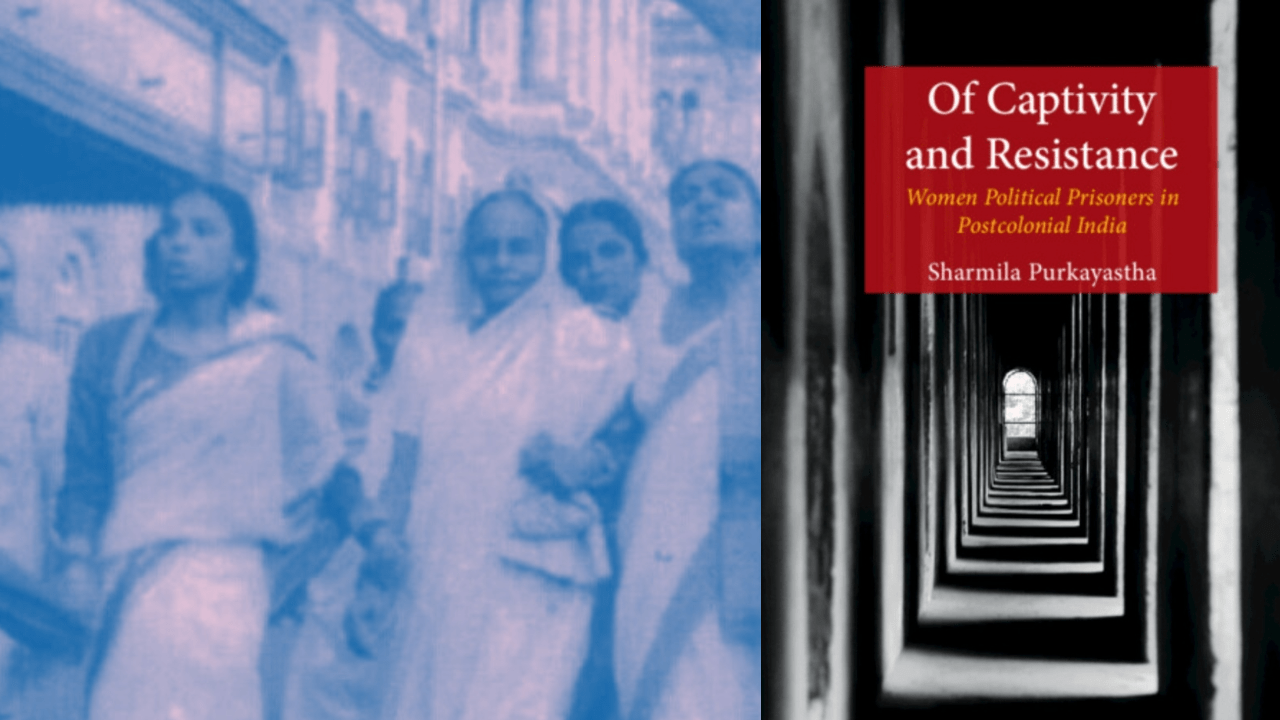

Towards the very beginning of her book, Of Captivity and Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India, author and professor Sharmila Purkayastha, dedicates her research- a culmination of several years’ worth of surveys and interviews and collecting testimonials- to ‘all those who have struggled behind bars‘. The words, simple though they may seem, are nothing less than a tribute to all those who have suffered through the carceral complex in India.

Much of the book, Purkayastha says, attempts to provide an account of Indian women’s political activity through the years by focusing on both their activism before their imprisonment and their lives while in captivity. With the adoption of the captive-political dialectic, the author envisions an intensive study into the links between organised political action and incarceration, as well as a gendered analysis of State violence.

Incarcerated for raising their voice against colonial powers or against the State (as during the Emergency), these individuals are often referred to as political prisoners in popular discourse, yet it could be argued that this namesake often ends up erasing the rich organisational work they were engaged in, or that such a term might just erase their very humanity.

In her first chapter, Purkayastha lays down succinctly the goals and scope of her research. She notes that a thorough study of women’s political participation in India can only be realised through what she terms as the captive-political dialectic. Much of the book, Purkayastha says, attempts to provide an account of Indian women’s political activity through the years by focusing on both their activism before their imprisonment and their lives while in captivity. With the adoption of the captive-political dialectic, the author envisions an intensive study into the links between organised political action and incarceration, as well as a gendered analysis of State violence.

With subsequent chapters offering gainful insight not only on the involvement of women in political movements from anti-colonial resistance to Naxalbari activities but also on the detention of such organisers and activists from the Emergency up till recent times, Purkayastha certainly lives up to the aims she states for her book, Of Captivity and Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India.

With subsequent chapters offering gainful insight not only on the involvement of women in political movements from anti-colonial resistance to Naxalbari activities but also on the detention of such organisers and activists from the Emergency up till recent times, Purkayastha certainly lives up to the aims she states for her book, Of Captivity and Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India.

Choosing her starting point as anti-colonial resistance, Purkayastha draws her readers’ attention first to historical records and studies that paint a fascinating picture of the involvement of women in resisting the British Raj. Much of popular discourse tends to brush over the ways in which women would participate in organisational and revolutionary work. Textbooks dedicate mere paragraphs to women’s roles in the fight for independence, betraying a lack of concern with regard to educating youngsters on the vast and complex history associated with the same.

Worse, recent arbitrary deletions in syllabi for Indian textbooks brought about by the NEP framework only indicate the tenuous position the valuable history of marginalised peoples holds in the minds of several privileged Indians. Sections in Purkayastha’s Of Captivity and Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India dedicated to examining women’s roles in nationalist politics are a fresh breath in that they offer fascinating perspectives on revolutionary women, many of whom have ‘practically disappeared from the annals of history‘.

Purkayastha adeptly guides her readers through a brief yet altogether enlightening run-through of resistance in colonial India. She notes the overwhelming numbers in which women turned up for Gandhi’s Salt Satyagraha and mentions how the idea of jail-going popularised by Gandhi was often an act punctuated with diverse experiences for women. For some, it meant an escape from domestic drudgery. For others, it was an opportunity to study and debate, to organise and radicalise.

Purkyastha dedicates an entire section in her book into studying Swadeshi women engaged in resistance. She examines briefly the ways in which women would be recruited into revolutionary groups- although initially maintaining a total ban on their recruitment and being “celibacy-driven secret societies”, these groups saw increased participation of women after 1914.

Moving onwards, Purkyastha dedicates an entire section in her book Of Captivity and Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India into studying Swadeshi women engaged in resistance. She examines briefly the ways in which women would be recruited into revolutionary groups- although initially maintaining a total ban on their recruitment and being “celibacy-driven secret societies”, these groups saw increased participation of women after 1914. Hired initially to provide shelter and divert police attention, women were soon assigned strategic roles involving fugitive revolutionaries.

Nanibala Devi, for instance, obtained the location of ammunition hidden by incarcerated Ramchandra Mazumdar by posing as his wife. Nanibala was ultimately apprehended by colonial police as an absconder, and subjected to sexual abuse at the hands of colonial forces while imprisoned, a sick and brutal treatment meted out to women who were caught. Her life, the author writes, is full of gaps and silences. Often overlooked by scholars, her revolutionary activity not only offers a glimpse into the harsh lives of women engaged in resistance during colonial times but also raises important questions surrounding the inscription of caste patriarchy within sacred nationalism. (Nanibala’s retention of caste prejudices and asceticism while in jail is briefly mentioned.)

Following a thorough examination of the colonial period, Purkayastha, with the adeptness of a seasoned guide, lands her readers at the site of Naxalbari action. There is a brief mention of nearly 20-30 women arrested in Kolkata’s Presidency Jail for their involvement in armed movements, followed by an essential look into Kalpana Bose’s life as a Naxalbari. Bose would go on to become the longest-serving woman political prisoner of the Naxalite era in Bengal. Through carefully sourced testimonials and studies, Purkayastha pieces together Bose’s story- from her days in college where the fires of revolutionary action were lit within her through issues such as hikes in college fees, to her life as a leader of the SFI, and her eventual integration into Naxalite politics, where she’d acquaint herself with Maoist writings, and ultimately be imprisoned after leaving for Ranchi with a large contingent.

Here, Purkayastha particularly raises questions surrounding militant movements that would attract young women and yet continue to mistreat them. Even Charu Mazumdar- Naxalbari’s chief ideologue- would evoke images of the ‘New Man’ amongst his comrades. His gendered conception of the armed rebel aside, much of the movement’s well-documented history fails to truly discuss or even mention the role of women in it. With the Naxalite movement being a particularly popular hotspot for academic and scholarly attention, Purkayastha discusses the drawbacks of the invisbilisation of women from what is clearly an essential part of Indian history. In an effort to counter the same, she analyses what little scholarship exists on militant women, such as discussing women peasants engaged in guerilla warfare and women involved in communist organisational work.

What follows these chapters is the author’s shift in focus from resistance to captivity- in sync with the dialectic she conceptualises at the beginning of the book. Incarceration of Swadeshi women presented what the author terms a conundrum- ‘… its presence was reordered within the bourgeois ideology and was utilized for defending fearless patriotism and … its “unspeakable truth” compelled sanitization…in keeping to bourgeois demands for chastity and purity.‘

Naxalites would often be subjected to brutal torture not only for extracting information from them but also to repress and defeat them for daring to question and call for the abolition of class relations in society. By attributing violent intention to all possible suspects, the State would mete out punitive punishment harshly. The punishment would be filtered through caste and sex. The horrors of torture inflicted on incarcerated women are elaborated on by the author.

Naxalites would often be subjected to brutal torture not only for extracting information from them but also to repress and defeat them for daring to question and call for the abolition of class relations in society. By attributing violent intention to all possible suspects, the State would mete out punitive punishment harshly. The punishment would be filtered through caste and sex. The horrors of torture inflicted on incarcerated women are elaborated on by the author.

For instance, Purkayastha discusses the case of Shipra Roy- ‘slung upside down by an iron rod… [police] continuously beat her with a metal strip‘. Although few testimonials exist with regard to custodial rape, the author brings to light important conversations surrounding the sexual nature of torture inflicted on women. Often, women were subjected to abuse and assault at the hands of both male and female guards (such as in the case of Ashima Poddar).

Nandita Ghoshal’s case is a rare instance wherein a rape case was registered against officers, although it is terrifying that the cops attempted to coerce Ghoshal’s doctors responsible for terminating her pregnancy into lying that the time of conception predated her arrest. What follows are several chilling accounts of women subjected to inhumane treatment during detention, bringing to light the reality of the gendered nature of state violence.

It is towards the end of the book that Purkayastha reaches present times and culminates her journey along with her readers through the history of resistance and captivity. She notes the marked increase in convictions of women after the seventies and highlights the differential ways in which the Indian State deals with male and female convicts. For instance, while Sahba Habib’s male associate was released on bail, Habib herself, a member of the Hurriyat Conference, and imprisoned under the Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act, remained jailed. Habib’s alienation as a prisoner was further compounded by her identity as a Kashmiri. Habib even accounts for her harrowing experiences of racist isolation and their lasting effects on her psyche. Importantly, the author brings to light the ways in which Habib resisted at her own level against the carceral complex. When forced to attend Hindu religious programs, Habib would utilize her knowledge of Hindi to engage in conversations with her fellow inmates regarding patriotism and nationalism.

Briefly, Purkayastha even highlights the caste-based discrimination women would face while held in prisons. She notes how political organisers are often treated as criminals by the carceral State. She writes how the ‘combined efforts effect of state violence embedded in interrogation, incarceration and legal struggles are meant to break the political resistance of participants.’ She ends her chapter with a rousing call to decolonise penal power and incite conversations surrounding prison abolition and the perils of punitive punishment.

At a time when engaging proactively in politics becomes criminalised, and even such spaces dedicated to radical politics are revealed to alienate and often be hostile towards women, Purkyastha’s study of women’s captivity and resistance is a radicalising text that well and truly brings onto paper the vast history behind women’s participation in revolutions.

As activist Teesta Setalvad’s legal struggle continues and student politicians are detained and suppressed, it becomes important for citizens to question the gendered nature of State-enforced violence and the political repression that it aims for. Compellingly written and elaborately researched, Purkayastha’s historical account, Of Captivity and Resistance: Women Political Prisoners In Postcolonial India, is perhaps a truly radical piece of text in that it evokes a consciousness within its readers with regard to the complex interplay of gender, the State and the prison industrial complex.

About the author(s)

Mayank (he/him) is an 18-year-old student hailing from Delhi. He is particularly interested in offering cultural and literary critique through the lens of feminist and queer studies. In his free time, Mayank enjoys reading theory and is known to appreciate pictures of pet cats.