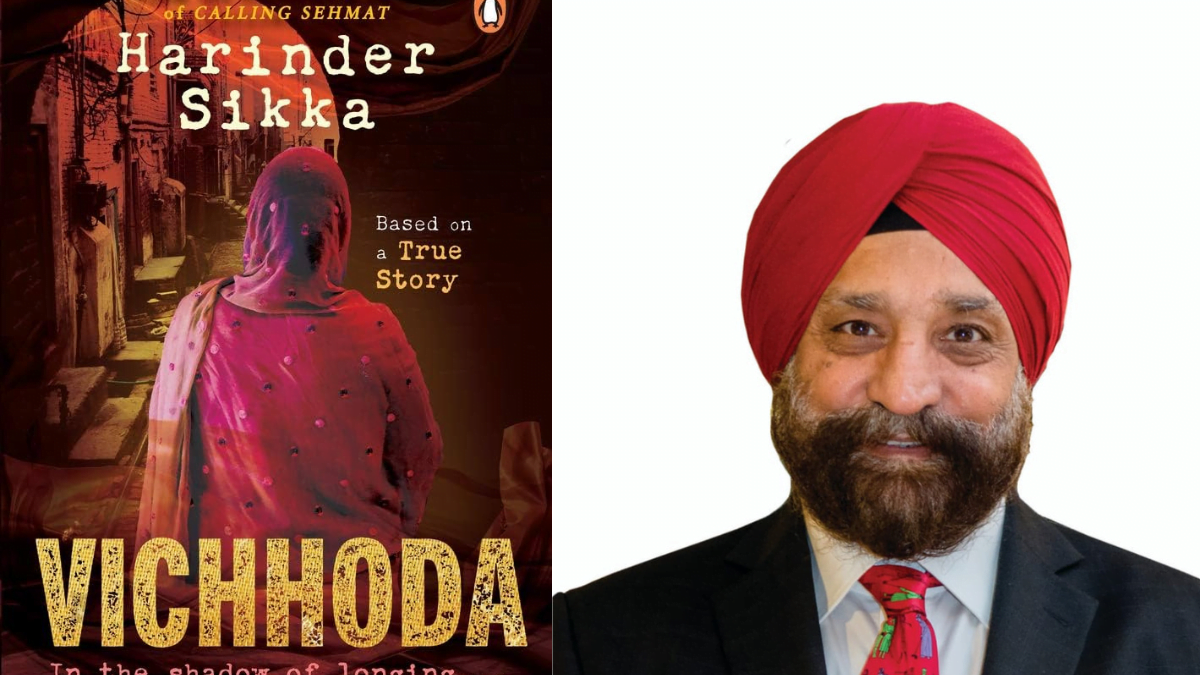

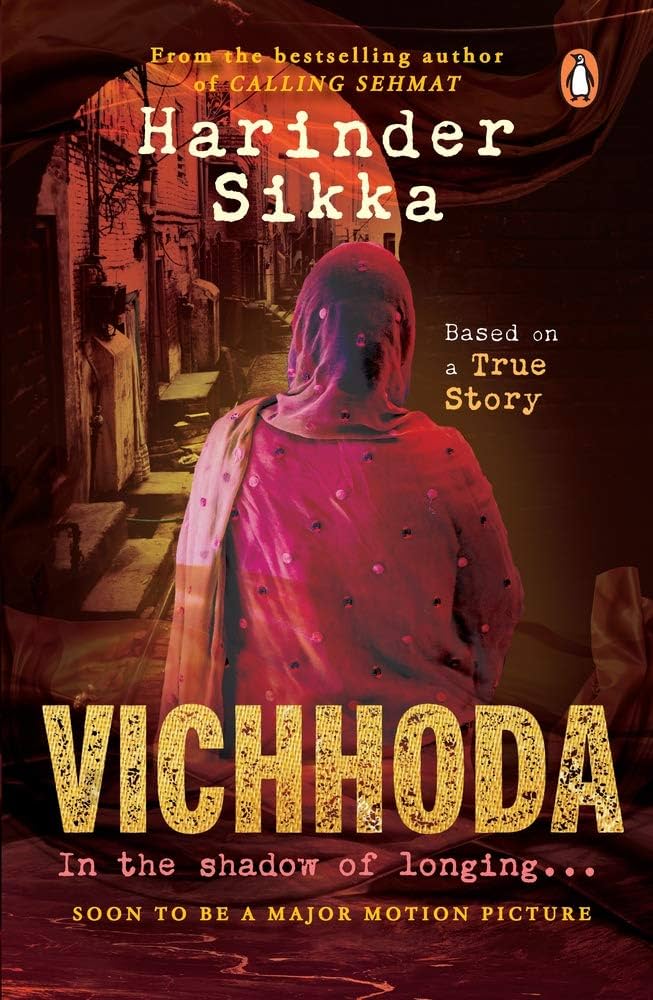

There have been few Indian authors who have successfully managed to showcase India’s history from a woman-centric perspective. Harinder Sikka is one of them. Best known for his novel- Calling Sehmat (which was later adapted into a Bollywood movie- Raazi), Sikka is a retired navy Lieutenant-Commander. In his latest book Vichhoda , he writes about a woman’s resilience and her efforts towards rebuilding life, after she is faced with tragic events. Set against the backdrop of the Partition, the narrative of the novel proceeds from the post-Partition riots, and slowly transitions to the Nehru-Liaquat Pact and the Indo-Pakistan wars.

The plot of the novel centres around Bibi Kaur, a Pakistani Sikh woman who loses her family in the Partition riots. She is rescued by a Pakistani Muslim man and married off to his son. Now living a new life with her sons, Bibi is separated from her family again due to the Nehru-Liaquat Pact and sent to India. How Bibi manages to deal with this separation and the kind of life she leads ahead forms the plot of Vichhoda. Through Bibi’s character, Sikka makes a social commentary on many important issues, which have been discussed in detail.

The role of marriage in Vichhoda

Sikka introduces the readers to the first theme- the concept of marriage. He narrates an incident from Bibi’s early life, when she is married-off during the riots so as to ‘protect’ her. What does this instance of marriage indicate?

Sikka sheds light on all those real women who faced a similar fate during the riots, and we as readers are forced to imagine if marriage is anything more than a means to protect community honour.

Carol Pateman, a renowned feminist has argued that marriage offers men access to female sexuality. This applies to Bibi’s life, as marriage would give her husband complete control over her sexuality, and avoid Bibi’s bedbi (dishonour) by other men during the riots. By talking about this instance, Sikka sheds light on all those real women who faced a similar fate during the riots, and we as readers are forced to imagine if marriage is anything more than a means to protect community honour.

Women and the Indian state

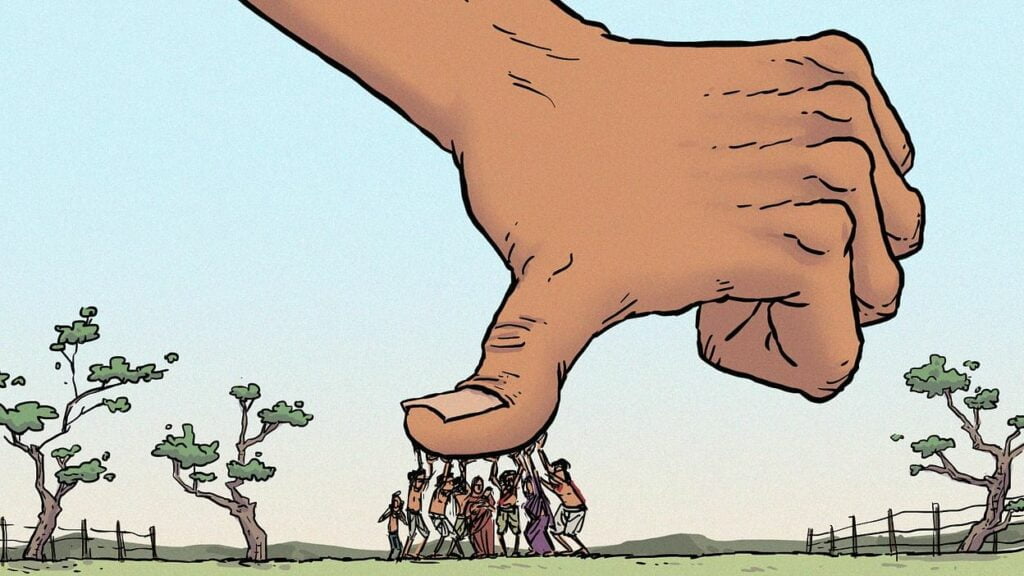

The second theme Vichhoda highlights is the patriarchal role of the state, and the role of women within it. In Vichhoda, Sikka shows the different roles women play within the state. Firstly, all modern states have a public and private sphere. Bibi’s life is confined to private sphere- her house where she looks after her children. Sikka even writes that she had fulfilled ‘roles of a mother, daughter and wife.’ Hence, modern states have denied women a public space- their role is limited to nurturing children and therefore to supply the state with future labour (a phenomenon called the ‘Mommy Track’).

Secondly, for any state, the right to citizenship is an important way of distinguishing between citizens vs. ‘outsiders.’ For Bibi, even her citizenship is contested- she is a Sikh believed to be Indian when her entire life has been spent in Pakistan. Through her case, Sikka manages to showcase a grim reality of women’s role in any state- their citizenship is to be decided by men in power, and these women possess no agency or control over their own fate. Here, we are forced to ask- What determines an individual agency- caste, religion, or the gender of those taking these decisions (men, in most cases)?

Vichhoda can also be read from a Marxist-Feminist lens, where the state is a patriarchal institution of the bourgeois. For Marxist-Feminists, class struggle is important for the weathering away of the state, an institution where women perform the unpaid task of creating future work force. Sikka has skilfully showcased Bibi in this Marxist imagination. Yet, what makes Bibi’s character so different is that her personality is full of complexes. This means that while Bibi does fit into the Marxist-Feminist understanding of a woman’s role in the Indian-State, in many cases, Bibi is also an exception to this description.

Throughout Vichhoda, readers see Bibi playing the role of a housekeeper, where she looks after her children. In this manner, she is like any ordinary women subjected to the state’s patriarchy- her role is limited to her family and she is not paid for her role in raising the future labour force. However, Bibi’s character is full of nuances, devoid of any strict black and white distinction. For instance, Bibi has no false consciousness– she knows nobody would protect her when she faces assault and that she must fight for herself.

Similarly, Bibi does not sit idle when her husband is fighting the War. Instead, she involves herself in teaching the local village children. By depriving Bibi of any false consciousness and giving her a sense of reality, Bibi’s character is also a deviant to Marxist understanding of women.

Role of caste and property in Vichhoda

While caste and property do not feature explicitly in Sikka’s narration, he introduces these two dimensions subtly. Firstly, Sikka talks of Bibi’s grandfather, who maintained friendly ties with British and owned private property, a house named ‘Sardar House’ which employed half the men in his village. Secondly, Bibi’s strong economic background tells us she belonged to a respected caste, though Sikka never directly mentions it. This property-caste nexus becomes significant from a feminist understanding, since both property and caste can be protected only by regulating female sexuality. Losing a woman’s honour to men of another community meant losing the right to claim property and status. It was believed that since men of a high-caste were unable to protect the honour of their women, they also had no right to claim private property or societal status.

However, Sikka, throughout the narration, does not account for one important factor- Bibi’s high caste made things much easier for her during the post-Partition riots. This is not to discredit Bibi’s struggles, but Sikka makes life much convenient for Bibi after coming to India. She marries an Army officer and is easily accepted by Virk’s parents, she becomes a prominent figure within the Army wives’ circle, and is loved and respected by people around her.

If Bibi was a Dalit, would she be subjected to the same respect and honour by the community? For many Dalit women of her age, Bibi’s character might come across as privileged or at the best, unrelatable.

If Bibi was a Dalit, would she be subjected to the same respect and honour by the community? For many Dalit women of her age, Bibi’s character might come across as privileged or at the best, unrelatable. Perhaps, Sikka missing out on the caste factor emerges as the biggest drawback of the novel.

In spite of such limitations, Bibi’s portrayal becomes Sikka’s way of showcasing the kind of women he would like to see in literature. Sikka shows Bibi as a strong woman, who does not need a man to complete her. She remarries, travels to Pakistan all by herself, and has learnt to defend herself. From a meek and timid woman, we see her becoming a strong and self-reliant individual. In this manner, Sikka’s portrayal of Bibi is strong and inspiring, which makes Vichhoda a must-read for any reader seeking strength and comfort in times of adversity.

To conclude, Vichhoda goes beyond simply narrating the events of Bibi’s life. By centering its narrative around a woman against the backdrop of violence, Sikka touches upon several themes and ideas throughout the novel. While Sikka overall does a good job in writing a female character, one can wonder if Bibi’s character would have been different if it were written by a woman. Perhaps we must ask- Would the female characters in literature be any different, if they were written by women and not men? We, as readers, must start asking ourselves this question to understand literature better.