By: Suresh Kumar Mohapatra

Odisha is known for its diverse tribal population and is home to 62 tribes, including 13 particularly vulnerable tribal groups. Approximately 23% of its population speaks 21 tribal languages encompassing 74 dialects.

In June, the Odisha Cabinet chaired by Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik recommended the proposal for the inclusion of the Saora, a tribal language, in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution.

In the hilly tracts of southern Odisha, the Saora language holds prominence, with at least five lakh tribals speaking it, making it one of the most significant languages in the region, even as the younger population seems to be moving away from their traditional language.

“It will create an eco-system to facilitate research and studies anchored around preservation, promotion and propagation of the tribal language. Besides, activities such as publication, content creation and recognition will get momentum,” Scheduled Caste and Tribes Development Minister Jagannath Saraka told reporters after the Cabinet meeting.

New languages were added to the Eighth Schedule in 2004 also. Santhali, Maithili, Bodo, and Dogri were added to the list then.

In the hilly tracts of southern Odisha, the Saora language holds prominence, with at least five lakh tribals speaking it, making it one of the most significant languages in the region, even as the younger population seems to be moving away from their traditional language.

In the hilly tracts of southern Odisha, the Saora language holds prominence, with at least five lakh tribals speaking it, making it one of the most significant languages in the region, even as the younger population seems to be moving away from their traditional language.

Laxman Sabar (29) of Dharapur village says the younger generation is unfamiliar with writing the tribal script. “Only about 30% can write the language fluently while all tribal people speak this language in their family and community“. “Saora is unpopular among tribal youth as the use of language is limited to family and community… after a child reaches primary education level, they start to forget their own tribal language,” says Prasad Sabar of Sandhikhola.

According to Biswanath Sabar of Radhuguda village, the lack of use of language in the professional sphere is the reason for the reduced popularity of the local dialect. “The new generation does not speak the language… and it is of not much use in higher education or employment.”

According to Falguni Sabar, a researcher from Gunpur, the lack of popularity also means that many tribal children drop out of school. “The tribal children only know their language. Once they go to schools, they are introduced to newer languages that they are not able to pick up… which is why they find it difficult to cope in school and drop out,” she says.

According to Falguni Sabar, a researcher from Gunpur, the lack of popularity also means that many tribal children drop out of school. “The tribal children only know their language. Once they go to schools, they are introduced to newer languages that they are not able to pick up… which is why they find it difficult to cope in school and drop out,” she says.

Naba ghana Sabar of Jaitili village says the language is not used in any official capacity and youth are not interested in learning Saora. “The trend is to move away from it for languages like English and Hindi, which makes it less popular among the younger population,” Naba ghana says.

“The only way this will change is if the language is propagated with the government and community help,” says Anusuya Gomango of Gulumunda Pakka village.

There are efforts to launch textbooks in the Saora language in government schools. Sabar of Soura Rella village says the new efforts will help tribal children learn their language in school.

Brundaban Sabar of Perupango village says dropout rates will decrease, which will help in the reduction of tribal illiteracy. “Thus education will be easy for tribal children if every subject textbook will be published in their script. It will help in the preservation and promotion of tribal culture,” he adds.

However, the fight for prominence is not new for the Saora language.

Saora: A peek into history

The Saora language belongs to the Austroasiatic language family and is primarily spoken by the Sora tribal community.

“Sora is one of the oldest tribes in India and is also known by different names Savaras, Sabaras, Saura and Soura. Soras belong to a primitive tribal group and stay in parts of Rayagada, Gajapati and other parts of Odisha, numbering somewhere around 10 lakh. Spreading across Bundelkhand in the west to Odisha in the east, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Bihar, their population comes to about 3.10 lakh. But their major presence is in Odisha,” says a language researcher Akhyaya Sabar of Bahupadar village.

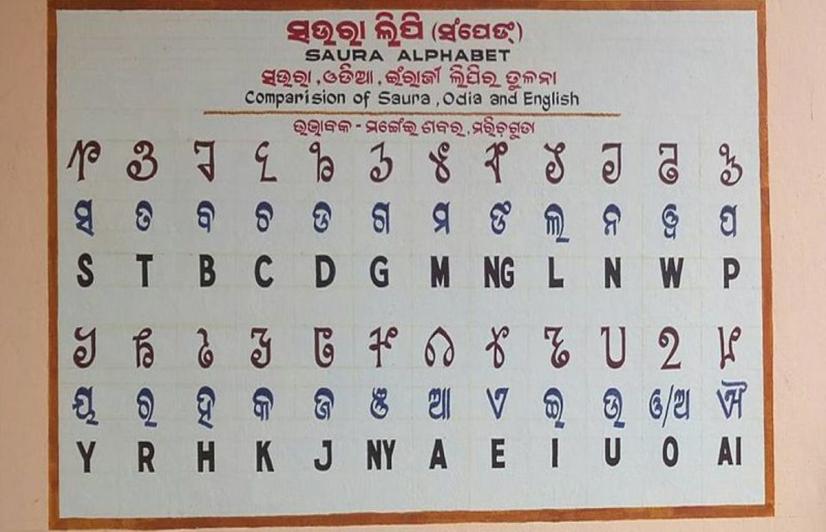

“Saora is an ancient language that has been traditionally spoken by the Sora people for various purposes, including religious rituals, cultural events and personal communication. But the script for the language did not exist until the 1900s… The script is unique and distinct, with its own set of characters representing phonetic sounds. It is written from left to right,” he adds.

Mangei Gomango of Marichaguda near Gunupur discovered the Sorang Sompeng script. The script has been passed down through generations within the Sora community, and its origins are deeply rooted in their cultural history. Sorang Sompeng has been recognised, studied and documented by researchers, scholars and community members who have worked to preserve and revitalise the script.

Mangei Gomango of Marichaguda near Gunupur discovered the Sorang Sompeng script. The script has been passed down through generations within the Sora community, and its origins are deeply rooted in their cultural history. Sorang Sompeng has been recognised, studied and documented by researchers, scholars and community members who have worked to preserve and revitalise the script.

“My grandfather was born on June 16, 1916… He started his career at the age of 16 as a school teacher in Khilamunda village… After a few days, he became a compounder at the office of the Cuttack chief medical officer in Odisha,” says Digasmin Gomango, grandson of Mangei Gomango.

“This was his first time staying away from home, and since letters were slow and telephones were not that common, he could not communicate with the family as much… After some days at Cuttack, his father and uncle Malia Gomango visited him. On reaching the office where Mangei works, they were made fun of because of the way they spoke and their traditional tribal garments and jewellery,” he says.

“The incident shook him. He used to wonder why people made fun of his family and culture… while he was conducting his first postmortem examination, he realised that life has no value after death. Similarly, language has no value without a script… He felt that a script would bring back dignity to his language. With that in mind, he resigned from his job and returned home to uplift his tribe,” Digasmin adds.

Malia Gomango had earlier studied the pronunciation of the Saora language. After his passing in 1935, Mangei Gomango continued his uncle’s research.

“The script came to my grandfather during a 21-day meditation session on Idmatara Leyangbur hill located in Marichaguda village near Padmapur. He saw divine light during penance on the hills of Marichguda in a supernatural event and got the information about the appearance of Akshar Brahma. it is believed that he heard about 25 alphabets and nine numbers during meditation,” he adds.

“After the discovery of the pronunciation and alphabets of the script, Mangei visited several places in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh along with his first disciple Nilambar Sabar for preaching his language and script,” local BJD leader Kailash Kraska says.

About the author(s)

101Reporters is a pan-India network of grassroots reporters that brings out unheard stories from the hinterland.