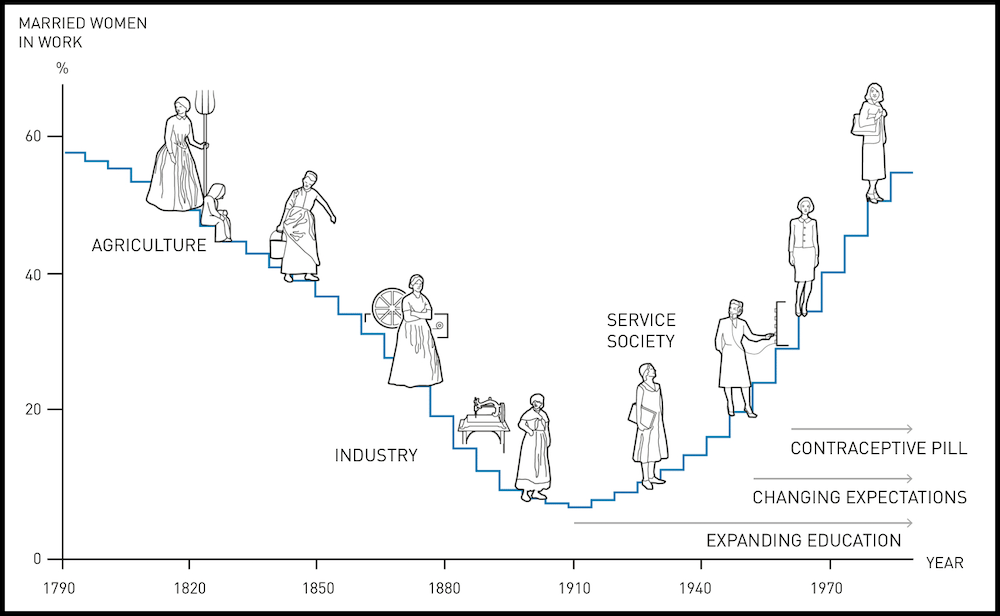

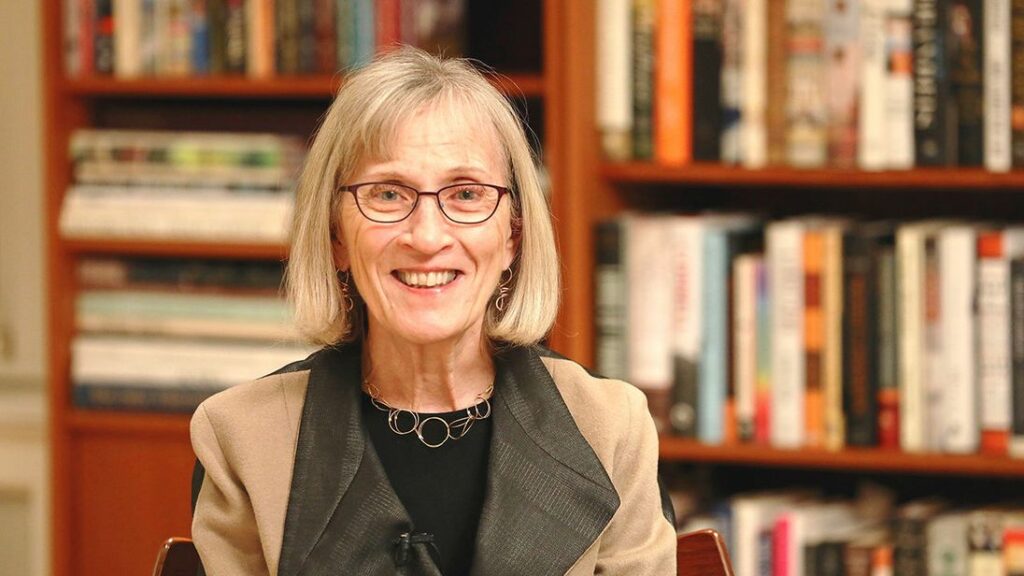

The study on women in the labour market has been provided by Claudia Goldin, the recipient of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. Goldin’s analysis of data spanning two centuries revealed a U-shaped curve: female participation first decreased in the 19th century before starting to increase once more in the 20th century.

Although women were earlier employed in agriculture, they withdrew when industrialisation emerged. Women began to enter the workforce as a result of the expansion of the services industry and the availability of contraceptive pills.

Regardless of this, Goldin’s research revealed that there was still a significant pay disparity between men and women in the same profession; in fact, this gap widened once a woman had her first child. Even though the majority of the data over the last 200 years emanated from the US, a careful examination of the variables contributing to gender disparity shows that they apply to women worldwide. Research conducted in a nation like India, where culture is a major factor in determining an individual’s occupation and income, might provide slightly distinct findings.

Perceptions of the pay gap

When FII talked to some women across India, met Devika, a 26-year-old married woman from Rajasthan who didn’t face any friction in her studies because of the absence of a child. Men’s and women’s careers and pay are essentially the same when they first start working, as demonstrated by Goldin, but they differentiate after children are born. Hence, Devika believes the ‘pay gap is an old story when women were not allowed to work outside the household.’

Some men from Kerala have provided FII with an analogous narrative when questioned about the gender pay disparity. ‘Even for casual labourers and daily wage labourers, there is no gender gap in Kerala. Kerala is very special when we compare it with other states.’

While Kerala is performing better than other Indian states in the Gender Parity Index (GPI), it is still unable to eliminate the gender pay gap.

According to the World Economic Forum’s annual Gender Gap Report 2023, India ranks 127th out of 146 nations in terms of gender parity, indicating that the whole country has been performing poorly.

Disproportionate incentives in the work field

According to the theory, women’s education levels increased steadily throughout the twentieth century, and in most countries, they are now significantly higher than men’s. Goldin showed how the availability of the contraceptive pill, which provided new avenues for career planning, contributed significantly to the acceleration of this momentous shift. Many forms of contraception had already reached Indian markets by the early 1930s, allowing Indian women to devote more time to their career growth and be partially free of household duties.

According to Goldin’s study, increasing the age of marriage and promoting higher education are the two main ways to encourage more women to enter the workforce. Family life shaped wage gaps—it widened when mothers cut their work hours.‘I had to give up my studies after matric as I was assigned domestic work due to a demise in my family; the kids were young, and there was no one else to look after them,’ Himachal Pradesh native Hamita Bano told FII.

According to Goldin, “if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who laboured long hours and worked particular hours,” the gender gap may be bridged or minimised. As a result of the disproportionate incentive, women bear a greater share of the household load. Women are groomed to be homemakers even before marriage, particularly in India, where they are given heavy house chores starting at age 5, which saps their vitality as young girls seeking to fund themselves.

Additionally, due to morning work hours, the profession of teaching seemed the only one that could fulfil the predetermined route and duty while juggling work and the home. ‘Men get support from family; women have to take up jobs on their own. It gets difficult for women to work alone; it’s easier when you have support. Being a lady, support is essential. Also, the fact that women have to go back home and complete the unfinished household chores, which are off-limits of their male counterparts in a domestic setup,’ said Hamita Bano, who later managed to do a technician course but couldn’t commit to the job because of night duty and childcare responsibilities.

When there is a critical requirement for significant investment in women’s education, there are very few ongoing, inactive programmes that aim at boosting the employment of women.

Juxtaposed economic history of women in work

Due to the shift in employment from agriculture to manufacturing, services, and construction during the past 20 years, India’s female labour force participation rate has decreased. According to Goldin, there was no rising trend in the number of women entering the job market during this time; rather, there was a U-shaped curve.

Azim Premji University’s State of Working India survey also reveals a U-shaped trend for married urban working women in India. The likelihood that a woman will go to work decreases as her husband’s income rises and then climbs once more when it surpasses ₹40,000 per month.

Women only make 76 per cent of what men do, which indicates a significant gender pay disparity. Married women’s participation declined as society moved from an agrarian to an industrial one in the early nineteenth century, but it began to rise again in the early twentieth century as the service sector expanded.

In India, however, the Industrial Revolution began in 1854, when Bombay established Asia’s first steam-powered cotton mill. These modernised cotton mills grew slowly at first, finishing their expansion in the 1870s and 1880s. This undoubtedly increased employment prospects near the end of the 1800s, when industries fully developed, but not for women due to household duties.

Growth in the service industry began in the middle of the 1980s, but it gathered up in the 1990s when India launched several economic reforms in response to a serious balance of payments crisis. It is challenging to draw parallels between the developed and developing worlds due to the disparity in notable years of development.

‘If you look at the history of early industry in many places in England, Japan, or in certain industries also in the US, you see a labour force that is pre-continentally women, not so in India. In India, industrial labour has never been predominantly female. Women have always been at the periphery of the industrial labour force. There’s a lot of very interesting sociological work that historically illustrates how, especially when jobs were scarce, for example, in Jute, there’s this very interesting work by Samita Sen and others that shows that as jobs become more and more scarce, women are getting displaced,’ states Meeta Kumar, a professor from the economics department at Miranda House.

Kumar further states, ‘A lot of the activities where female employment is disproportionately large are the first to get mechanised. Post-independence, also when, for example, the jute industry begins to stagnate, jobs become scarce, and women are actively discouraged from continuing in jobs where, for example, they can be replaced either by sons or just that kind of thing. So there’s a whole bunch of things going on here. If you look at the agricultural sector, a lot of female participation in agricultural work was just considered household chores for a long time, it is not “labour,” even though it is vital to production. It was recognised as labour.’

Structure of India’s economy and employment

India still relies significantly on agriculture. Since one of the main sources of income in the country is agriculture, India has never really become a manufacturing nation. In contrast, the Indian economy took a different path, with a shift away from agriculture and towards the creation of small-scale businesses rather than fully developed industries.

The country’s significant resources are still being utilised in the production industry, which serves very low wages and more abate wages to women. Changes in technological advances in agriculture displaced a lot of women in India, but good jobs in other sectors didn’t emerge for them, leading to a drop in the number of working women. Given that agriculture continues to be India’s primary source of income, her conclusions are more appropriate in urban settings and less so in rural ones.

Women are vastly underrepresented in the labour force, and while their numbers are increasing, their incomes are far lower than men’s. Compared to 80 per cent of men, just around half of women work worldwide; they earn a lesser sum and have a lower chance of advancing in their careers.

Hamita Bano, who has a small eatery in Shimla in a Tibetan market, found passion in her job, only because she doesn’t like to stay jobless; hence, she pursued this work and prefers to have some independent money at her portion, which is empowering to her as she says, ‘It’s very important for women to be self-dependent; marriage can be done after 4-5 years, but for women, self-dependence doesn’t come easily.’

Women have penetrated the labour field, outperformed men in education and discovered purpose in their work, however, as Goldin’s research demonstrates, women still lag behind men in a variety of areas, such as earnings, labour market participation, and the proportion of people who succeed professionally. Despite her passion, Hamita Bano is unable to do much in her small business due to restraints.

Worldwide inequality

The gender pay gap persisted despite women’s passion towards work; in fact, the wage disparity between men and women in the same occupation widened when the first child was born. Tapasi Roy from Agartala, who has been a teacher for 25 years, responds, ‘It’s wrong for the system to work like that, but the world prefers a man over a woman for many jobs, and sometimes men are needed to do physically strenuous jobs that women are unable to do, but I do feel that my male counterparts are more relieved in work than I am because they don’t take on the burden of domestic work.’

“We’re never going to have gender equality until we also have couple equity,” Goldin claimed. While there has been a “monumental progressive change,” there remain significant inequalities that frequently trace back to women performing more labour at home. The factors stated by Goldin are valid worldwide, however, the gender disparity pattern is not uniform.