At this time of the year, the air quality in Delhi and its surrounding regions remains perilous, with an overall Air Quality Index (AQI) of 322 on Monday morning, categorising it as “very poor“. The air quality in India’s capital, Delhi, has deteriorated to a poor level, and further degradation is anticipated in the days ahead. Different localities, such as Mundka, Jawahar Nagar, and Jahangirpuri, experienced AQI readings that fluctuated between “very poor” and “severe” over the course of the day. Environmental monitoring organisations forecasted that Delhi’s AQI is expected to stay in the “very poor” category for the next two to three days and maintain a similar level for the following six days.

The sentiments shared by numerous Delhi inhabitants I engaged with revolved around a prevailing smoky odor in the atmosphere. ‘It will be worse post Diwali,’ hinted a friend. ‘We should not step out without wearing masks. It’s worse than COVID.’ Recommendations and reminders, such as the necessity of purchasing air purifiers, have become a common refrain.

What these responses reveal is that pollution has transformed the cultural landscape of Delhi, affecting work patterns, housing arrangements, transportation choices, and even the adoption of technologies. These dynamic factors and influences are intricately intertwined, making it challenging to untangle their web. They have given rise to new lifestyles and mental habits, as well as accentuated existing disparities and vulnerabilities, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation and environmental distress.

In 2019 alone, India experienced an estimated 1.2 million air pollution-related premature deaths.

Addressing air pollution is important. In 2019 alone, India experienced an estimated 1.2 million air pollution-related premature deaths. The yearly mean PM2.5 concentration in Delhi for 2021-22 stood at 100 μg/m3, which is a staggering 20-fold higher than the recommended WHO limit of 5 μg/m3.

The recent increase in air pollution is attributed towards Punjab recording 1,068 stubble burning incidents on Sunday, the highest this season. Although the state has reported fewer incidents compared to the same period last year, a late harvest in Punjab suggests that paddy stubble burning incidents may rise in the coming weeks. Weather is also a contributing factor. Farmers engage in stubble burning twice annually, during both the summer and the early winter. When they burn stubble for the first time, the warm winds disperse the smoke rapidly. However, during the second burning, which occurs in either September or October, the combination of colder temperatures and reduced wind speed causes the smoke to spread extensively.

Returning to Punjab’s Jalandhar district, the atmosphere is a blend of scents: earth, straw, pollen, and ash all mingling in the air. Over the district, one can observe the ascent of dense, inky plumes of smoke and soot. Sohan Singh, a farmer in the village of Kathar, reflects, ‘The window for harvesting paddy and sowing wheat is incredibly limited. Stubble burning emerges as the swiftest method to clear the fields.’

Bio-decomposer developed by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, turns crop residue into manure in 15 to 20 days, but do farmers have the time to wait for this long? Furthermore, it’s essential to recognise that employing a seeder combine is a significant expense. The combined use of this machine and a tractor can amount to as much as $15,000 (around ₹12,50,000). ‘This elucidates the reasons behind the prevalence of stubble burning among farmers; for many. It’s a matter of financial necessity,’ remarks a farmer in an interview with BBC. Additionally, even for those with the means to make this investment, obtaining the machinery has proven to be a challenge, owing to extended waiting periods and dwindling availability.

However, putting the blame of Delhi’s pollution on only stubble burning is not right.

The practice of stubble burning has a history, but its escalation gained prominence following the 2009 regulation that delayed rice planting. This intensification is clearly noticeable on air pollution charts, especially from around 2016 onward, and it reached its zenith after the Indian capital, Delhi, consistently ranked in the top 10 of global cities with the most severe air quality issues. In response to mounting pressure to address the problem, Delhi’s Chief Minister, Arvind Kejriwal, frequently points to stubble burning as one of the contributing factors to the city’s predicament. However, putting the blame of Delhi’s pollution on only stubble burning is not right.

In 2020, both experts and Union Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar have underlined that stubble burning represents just one of numerous pollution sources. Experts have additionally cautioned that concentrating solely on stubble burning might provide a convenient excuse for political leaders to evade accountability for not addressing local pollution origins within the city. These include emissions from vehicles and industries.

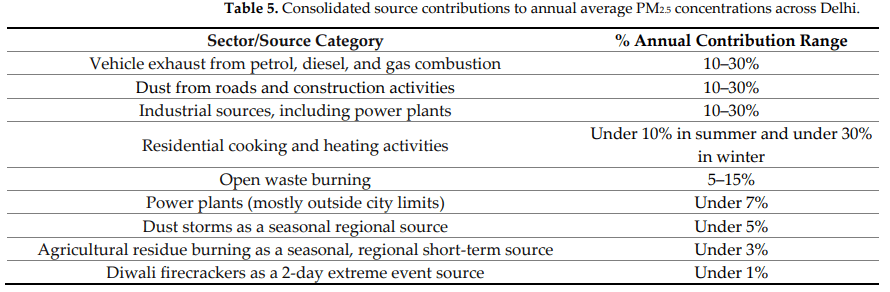

According to a 2023 research by the Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi based think tank, air pollution is not solely attributed to a single cause but rather arises from a multitude of sources. An amalgamated overview of findings from various source apportionment studies is compiled in the table below. The report emphasised, the key sources that require immediate attention are vehicle exhaust, road dust, construction dust, cooking and heating, open waste burning, and industries.

It further expanded that solving this issue extends beyond the city limits; it calls for a collective regional effort. The intricate link between the urban environment, public health, and city planning is undeniable, particularly in megacities. With a population exceeding 25 million in the airshed, pollution stemming from various sources like transportation, cooking, heating, waste incineration, and industries is an inherent part of urban life. To tackle this, pollution reduction should be an integral component of the city’s master plan. Urban planning initiatives, including traffic reduction, promotion of non-motorised transportation, establishment of pedestrian zones, and encouragement of mixed-use commercial and residential areas, are pivotal in achieving this objective.

Currently, The Environmental Minister, Gopal Rai, announced the initiation of the second stage of a Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) to address the heightened pollution levels

Currently, The Environmental Minister, Gopal Rai, announced the initiation of the second stage of a Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) to address the heightened pollution levels. Under this plan, all public transportation services, such as the Delhi metro and electric bus services, have received directives to augment their service frequency as a measure to mitigate vehicular emissions in the urban area. Furthermore, the minister revealed that, apart from the existing 13 pollution hotspots, dedicated teams will be dispatched to eight additional locations with elevated pollution levels.

He added, ‘..The Delhi government is working on all the parameters under the winter action plan…Last year, the AQI on October 29 was 397, and yesterday it was 325. So there has been an improvement… We are trying to improve it further. The next 15 days are very important, and we are preparing for them…All the industrial units in Delhi have been shifted from polluted fuel to natural gas. We have formed teams to monitor if anyone is using polluted fuel… The “Red Light on, Gaadi off” campaign is voluntary… I appeal to the people of Delhi to turn off their vehicle’s engine when there is a red signal…‘ In 2019, the Central Road Research Institute found that idling engines at traffic signals raised pollution by over 9%. At Bhikaji Cama Place, a PCRA study found a 62% reduction in idling engines following the campaign.

In the context of Delhi’s pollution crisis, it becomes evident that solutions like air purifiers, although individually adaptive, fall short of addressing the collective dimensions of the problem. The government must step in, not merely as a passive observer, but as an active enabler of change. Subsidies, stringent regulations, vigilant monitoring, and clear-cut accountability measures are imperative. Only through these proactive actions can we begin to tackle the profound ecological and social shifts that our city so desperately requires.

About the author(s)

Anuj is an urban practitioner and an independent writer. He's mostly interested in Feminist Urbanism and the intersection of various identities in the urban. He is a graduate of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements and has disciplinary training in Urban and Regional planning.