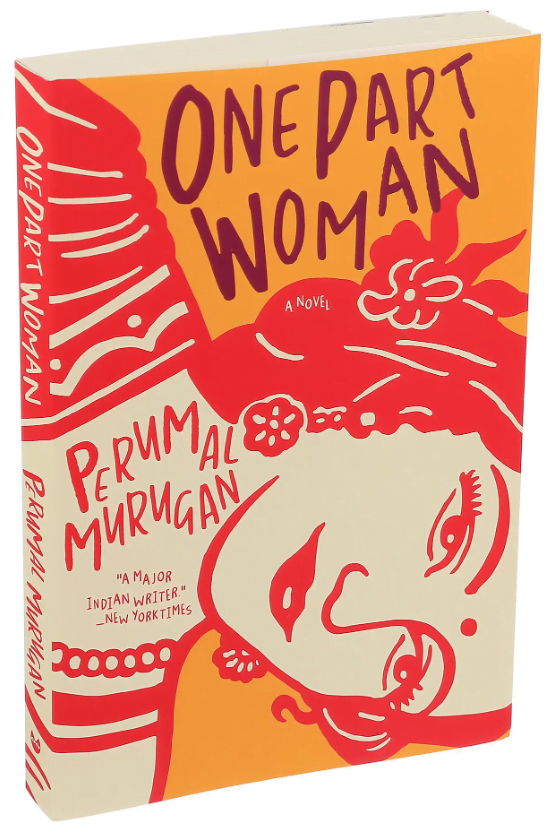

One Part Woman, a novel written by Perumal Murugan and translated into English by Aniruddhan Vasudevan in 2015 was banned for its controversial content as it questions and explores the site of parenthood and caste in society by placing the character Ponna in an otherworldly carnivalesque situation through the traditional chariot festival of Maadhorubaagan.

Perumal Murugan introduces us to the world of a childless couple Kali and Ponna who are continuously hounded by the taunts and insinuations of the community where societal expectations to bear a child take over their love for each other. In the novel Murugan talks about how a man’s worth is determined by his ability to cause morning sickness in his wife in the very second month and a woman’s worth is measured by her ability to reproduce. Their inability to fulfil this role in their community continues to remain in the back of their minds.

“She was thinking how the tree had grown so lush and abundant in twelve years while not even a worm had crawled in her womb. Every wretched thing reminded her of that lack.” The lack of the woman is traced back to the man, it is almost as if they mirror each other’s lack and are therefore together.

The anxieties and paranoia that revolve around the lives of Kali and Ponna are ridden by the curse of infertility, the Gounder caste community in the novel believes the land owners have a male child, cattle and orchards of their own – barrenness is regarded as a curse.

The novel is ridden with the pregnant curse that follows the two, the curse isn’t one of infertility but Brahmanical anxieties of land and progeny – in one such scene, Chellappan comes to the barnyard of Kali’s cows as they’ve failed to yield a calf despite two or three mating attempts. He then remarks, “This is just how cows are. No matter what you do, they never get pregnant. Just quietly change the cow,” – this remark is striking as it alludes to Ponna’s inability to reproduce. The barren woman is replaceable, if she cannot serve the interests of the high-caste man.

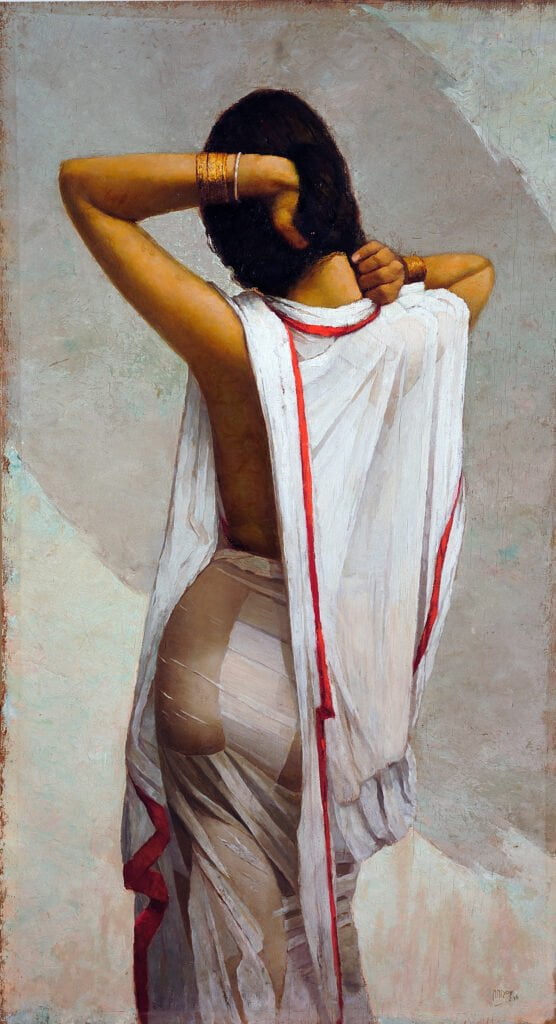

The novel’s first half is the circulation of the Brahmanical claim to the woman’s body, the novel counters narratives of the myth of marriage as a personal and private affair, not only is the household unit an annexation of the state but of caste Hindus in itself, the woman’s body and her liaison with her husband becomes severely visible in the eye of collective deification.

Another instance in the book sheds light on the caste superstitions that lurch over infertile women of the book, Ponna is invited for the puberty ceremony of Chellamma’s daughter – the custom was to ward off the evil eye wherein all the aunts were called to spin red balls of rice in a large circle around the girl’s body and then toss it away. Except when Ponna comes forward to do the same, Chellamma verbalises her anxieties – what if the girl becomes barren too? Was Ponna so inauspicious?

The novel’s first half is the circulation of the Brahmanical claim to the woman’s body, the novel counters narratives of the myth of marriage as a personal and private affair, not only is the household unit an annexation of the state but of caste Hindus in itself, the woman’s body and her liaison with her husband becomes severely visible in the eye of collective deification. This is when the village folks compel Ponna to attend the festival of Madhorubhagan wherein women are allowed to engage in consensual sex with any man, referred to as ‘god,’ to beget children. This child would be considered a gift from god.

Such a ritualistic event defies the conceptualisation of calendric time and opens up an alternative world for women, where a sexual exploit with a lowered caste man would not only not elicit condemnation but the child begotten from this affair could be seen as legitimate, in the eyes of her peers. Ponna’s decision to do so creates a harrowing bridge between the two, Kali’s anxieties of raising a son that isn’t his, and especially, isn’t of his ‘stature,’ plagued his hegemonic masculinity- one that is rooted in the groundings of caste and virility.

Kali does not allow Ponna to participate in the eighteenth day of the ritual at Karattur, because he is afraid of her participation with an untouchable. Murugan verbalises this anxiety in the following lines – “More than half young men roaming about town from the untouchable castes. If any of them gets to be with Ponna, I simply cannot touch her after that. I cannot even lift and hold the child.”

One Part Woman opens and ends with one tree: as the novel closes, Kali is seen considering whether to tie a noose to it, feeling betrayed by Ponna as she returns home pregnant having fulfilled the ritual. This transgression is committed by two non-actors.

The title of the book in itself draws attention as it is directly analogous to Madhorubagan, meaning half male and half female God in the same body but the English title does the job in exposing the lack the desire of Ponna to become a mother – motherhood is seen as the final step to become a complete whole woman.

The ritual then places her in a trance-like state of both unfamiliarity and morbid mesmerisation, the loosening of caste and gendered ties around the female body even though rooted in the patriarchal cult of pregnant women, Ponna experiences a female desire engulfed by curiosity and repulsion.

As Catherine Kohler Riessman vividly examines the plight of childless women in south India, she writes, “Women modify their reproductive lives as the need arises. Women grapple with their positions as victims of a culturally constructed subordinate status at the same time as they search for creative ways to resist subordination,” – Ponna’s life, however, isn’t this black and white, her pursuit of reproducing both her progeny and a world wherein she forms a complete woman, places her in a carnivalesque gathering akin to strange touch, the eccentric lurching pressure of fertility consumes the spatiality of the woman’s life, sexual desire is accentuated and hyphenated here. There is little to no room for her to exercise agency, the agency has already been asserted for her, and all she must do is carry out the mechanisation of picking her ‘god.’

Perumal Murugan’s One Part Woman dissects the myth that subsumes the ideological consciousness of gendered caste anxieties. In the words of Kalyanaraman, “In the gounders world view, the hard work put in by a Gounder male in his adult life is meaningless if there is no son to inherit the fruit of his labours.”

One Part Woman displays a melange of layers, sliced together into an amalgamation of anxieties, the anxieties around childbearing, the anxieties around marriage and its entrenchment in the woman’s sexuality, the anxieties of Kali revolving around caste-constructed masculinity and the overarching anxiety of negation – the negation of Kali’s identity in the face of a child that isn’t his, a wife that he cannot touch, and a domestic sanctuary that’s tarnished by Ponna’s transgression. The public and the private get enmeshed in the novel as it navigates through a spatially ambiguous world of bodies, gender and caste hegemony.

About the author(s)

Rida Fathima is a twenty-year-old Literature student at Azim Premji University with an interest in literary theory, film criticism, Marxist historiography and oral archives. She is interested in critiquing and analysing media through a feminist anti-capitalist lens.