Dr Rakhshanda Jalil is one of the most influential academicians, translators and literary historians in contemporary India. As someone who has published over 25 books so far and over 50 academic papers as well as translated the works of renowned writers like Premchand, Saadat Hasan Manto, and Intizar Hussain, she discusses the small organisation she runs called Hindustani Awaaz in this interview with FII as well as her connection with Delhi as a city and her views on the state of minorities in India.

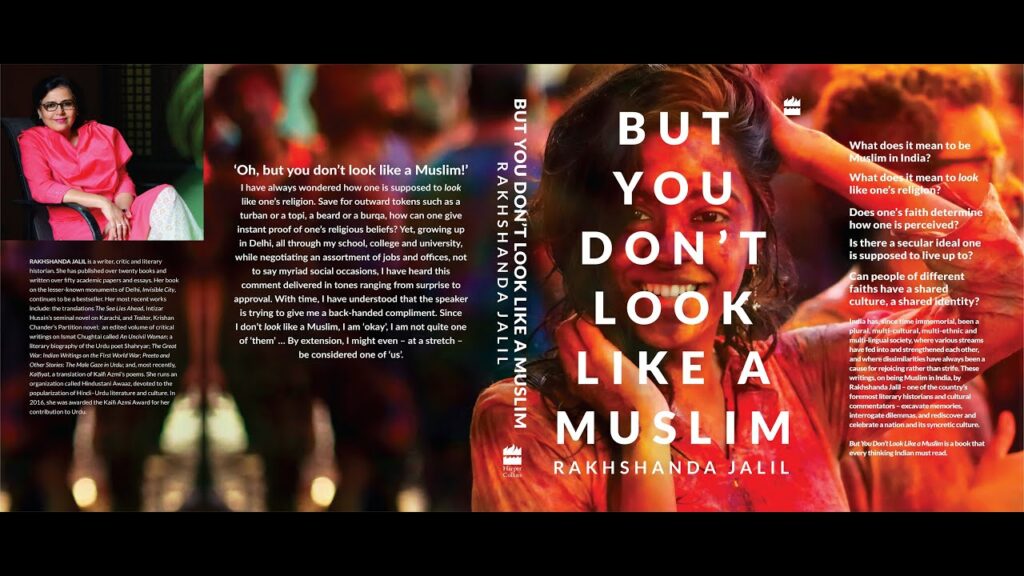

FII: ‘But You Don’t Look Like a Muslim,’ is an interesting collection of essays as it explores the idea of who a Muslim is and how we define one, especially if the person does not “look” Muslim. How do Muslims navigate political and religious identities today in India?

Rakhshanda: But You Don’t Look Like a Muslim is a collection of 40 essays written over a while. Muslimness is a motif that runs throughout the book, the idea of being a practising Muslim in India, not looking like one but being one and all the things that come with it. The essays are on culture, identity, politics and literature.

While Urdu is not the literature of Muslims alone and many Urdu writers are not Muslims, a considerable number of great writers are Muslims though. So Urdu writings also open a window to some extent into Muslim lives. This is the reason why I chose to include Urdu in the four sections that I have in the book.

The title also asks the most provocative question. It talks about identity, and how the majority feels an overwhelming need to tag the ‘other,’ to look at people as stereotypes, to divide people into “Us” vs “Them,” some are seen as “one of us,” others are not. What is this “one of us,” I ask. We are all Indians so why do we go by appearances? Is a woman in hijab or a person from Madras in lungi not “one of us?”

The layered identities that all of us – as Indians – possess should have ideally brought us together; alas it hasn’t. Anekta mein Ekta (Unity in Diversity) was a slogan in my youth; by and large, the government, and the people, lived by it. I was born in 1963 and there were traces of Nehruvian India still left in my childhood. Diversity was meant to be celebrated.

Recently, I have seen an insistence on everybody looking the same, behaving the same, dressing the same, and even eating the same food. This, to my mind, is contrary to the very Idea of India. For a lot of people, how you look and how you sound are more important than who you are.

FII: You have translated stories of Premchand, Saadat Hasan Manto, Intizar Hussain and many others. How would you like to comment on translation studies as an important and emerging academic field in India?

Rakhshanda: I did a BA and then an MA in English Literature from the University of Delhi way back in the 1980s. It was an Anglo-Saxon course then; however, I am very happy to say that things have changed a lot from my time. An average Indian child knew more about Wordsworth than Ghalib or any other poets from other languages. Now, things have changed to the extent that whether it is any university in India, even at the undergraduate level, there is a fair amount of Indian writing being taught to the students of literature. It is not just English literature anymore but “Literature in translation.”

So, writers like Manto and many others are finding a space in the curriculums and because they are making space, there is a legitimising of literature. If you walk into any bookshop, translation is being given space. Even an airport bookshop has some books from different kinds of bhasha literature in translation! This means that literature in translation is making inroads into public consciousness.

I do believe in a multi-lingual, multi-cultural, multi-ethnic society such as ours, translations form a valuable and much-needed bridge. Even financially, publishing translations is viable now – all of which is excellent news for translators.

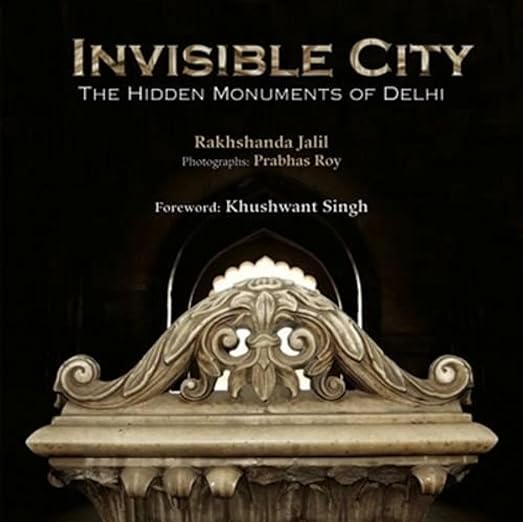

FII: ‘Invisible City: The Hidden Monument of Delhi,’ explores Delhi’s historical places in a detailed and interesting manner. Could you elaborate more on your connection with Delhi as a city and what has inspired you to research its history?

Rakhshanda: I was four years old when my family moved to Nizamuddin East in Delhi. Nizamuddin East had a lot of monuments, there was the Humayun’s Tomb and many other historical places. I grew up in Delhi where these historical monuments were not just picture-postcard-perfect little motifs that stud the cityscape and added scenic value but were places people went to.

I grew up in Delhi where these historical monuments were not just picture-postcard-perfect little motifs that stud the cityscape and added scenic value but were places people went to.

Rakhshanda Jalil

My mother would take us to picnics at these old monuments regularly, even the Delhi Zoo had a lot of monuments inside it many of which have gone. I have seen Delhi studded with monuments and I have seen many of them disappear too. So there was a childhood interest in built heritage fostered by my parents who would take us out to see and marvel at these old beauties in our midst.

I have not studied history, but have always been interested in built heritage. I began writing a column in The Times of India when it started the TOI city edition. I used to live in Gulmohar Park and nearby there was Makhdoom Sabzwari’s Dargah; by the time I started writing these columns Delhi had changed and so had people’s attitudes towards the past. People had stopped going to many of these places.

I started the column called The Invisible City because I felt that these 9 or 10 cities on which New Delhi has been built are there but they are invisible. People took shortcuts through them when out for a walk or took their dog for a walk yet these places did not register on their mental radar. We as a people stopped knowing the difference between a maqbara and a mahal, between a dargah and a chhatari or a baradari. These are broad architectural divisions and I am not saying everybody needs to be an architect to know these terms but there should be some sense of investment in the city you live in.

We have to learn from other ancient cities like Rome and Istanbul where people have learnt to co-exist with the past. Urban renewal does not mean effacement of the past. We have to live with the buildings, in and around them.

Rakhshanda Jalil

I began writing the column and moved to the magazine called The First City. These columns went on for a long time and I felt I had enough columns to make a book. The book was very well received and my publisher told me that it is one of the best-selling books in Delhi and always in print. There is something about the book written by a non-expert, it is written from the point of view of empathy for the city and by somebody who has a regard for the past.

I see the past as a continuum. I don’t see it as something we can cherry-pick. We cannot pick what suits our ideology and beliefs and disregard the rest. We have to embrace all of the past, the good and the bad. Our liking and our politics should not influence the past yet we live in a present where our present is defining our past.

A book like Invisible City becomes important in the times we are living in. We have to learn from other ancient cities like Rome and Istanbul where people have learnt to co-exist with the past. Urban renewal does not mean effacement of the past. We have to live with the buildings, in and around them.

FII: You started Hindustani Awaaz as an organisation devoted to the popularisation of Urdu literature. Urdu as a language is gradually disappearing, especially among the youth and there is a small population left who is interested in Urdu literature. How have you made Urdu accessible to them with the help of your organisation?

Rakhshanda: If I had infrastructural support or sponsorship, I would try to teach Urdu to as many people as I could. But I have neither and hence I thought of starting Hindustani Awaaz; it neither takes money nor gives any to anybody. We do not even have our bank account, so there is absolutely no financial give and take of any kind. Considering that we do not have money, my intention was and still is that I want to make Urdu accessible to people through content-based programming.

Given that I do not have institutional support, I hope to give people a taste of Urdu zubaan and tehzeeb, literature and the culture associated with it; at best I can open a window into it and hope that people will like what they hear and explore the rest on their own through translations, transliterations and further exposure. Events at Hindustani Awaaz are very intensely curated; there is no randomness to them. I choose a topic and do everything entirely on my own.

My two daughters help me with publicity and marketing, but in terms of content, it is just me. A fair amount of research and reading goes into what I want to talk about. We ran a series called New Urdu Writings for many years where we would pick one new book in Urdu/about Urdu each month and have a panel discussion around it.

It is a question of reaching out to young audiences, not the usual grey audiences. By consciously making our events open and accessible, with no entrance fee or registration, I think we are managing to get a fair amount of young people on board.

FII: What are your thoughts on the marginalisation of religious minorities in India, especially in the current times?

Rakhshanda: It is not just saddening but also shocking. Like I said, I grew up in a very different city. I am not saying that I did not witness any communal riots, of course, Moradabad happened and Nalli happened and so many other big and small outrages during my growing-up years. It caused serious shock and horror amongst people. Now, the outrage has gone out of our lives and we do not react.

I strongly believe more and more people need to call out the elephant in the room which is communalism, and marginalisation of minorities, Dalits, tribals and farmers. Women are marginalised anywhere in the world even though they make up half the total population.

Civil society thinks it is happening to somebody somewhere else, it is not affecting our lives. I strongly believe more and more people need to call out the elephant in the room which is communalism, and marginalisation of minorities, Dalits, tribals and farmers. Women are marginalised anywhere in the world even though they make up half the total population.

Be it the marginalisation of women, minorities, tribals, or anybody who is seen as not an equal player, I think all of this should be called out. As civil society, the biggest weapon we have is calling out. Not having the binaries of “you” and “me” but instead co-existing – rather living together separately but peacefully.

FII: Lastly, what would you like to say to aspiring academicians, writers and historians in India?

Rakhshanda: To young people, I would say, first and foremost: read, read, read. Everybody is in a hurry to write. I go to universities and the usual question is about writing, my question to them is how much do you read? Aap ki foundation agar mazboot nahi hai, to aapki imaarat kaise khadi hogi? (If your foundation is not strong, how will your building stand?)

The new generation wants to run before it can even walk. So the haste that I am seeing to get published and be authors, this haste is in the long run not good. You need to read eclectically voraciously, you need to read all kinds of things. If you are a political scientist, what is stopping you from reading literature? Or even other disciplines?

If Amartya Sen can talk about the Bengal famine and its devastation, and if a person like me could access it who is neither a political scientist nor an economist, everyone else can do so too. Do not be in a pigeonhole, do not be confined behind a picket fence of specialisation. Rise above it.

Cross-fertilisation of disciplines is very very important. My grandfather used to say this and I love to pass it on, he used to say that if he were stuck on an island and managed to just get a dictionary to read, he could never get bored. The habit of just picking up a dictionary and reading is wonderful. You can find value, interest and knowledge in anything.

The interview has been paraphrased and condensed for clarity

About the author(s)

Zainab is a literature student at the University of Delhi. She loves stories, books, cinema and humans too, sometimes!