Shabnam Hashmi, born in 1957, is an Indian social activist and human rights campaigner, who is actively working towards peace building and communal harmony in the country through her organisations like ANHAD. Holder of the “Woman of the Decade,” award by the Women Economic Forum, Shabnam Hashmi, in conversation with FII, talks about communal harmony, her years of activism and the current political state of India.

FII: Tell us about your childhood, your aspirations and what was your journey like.

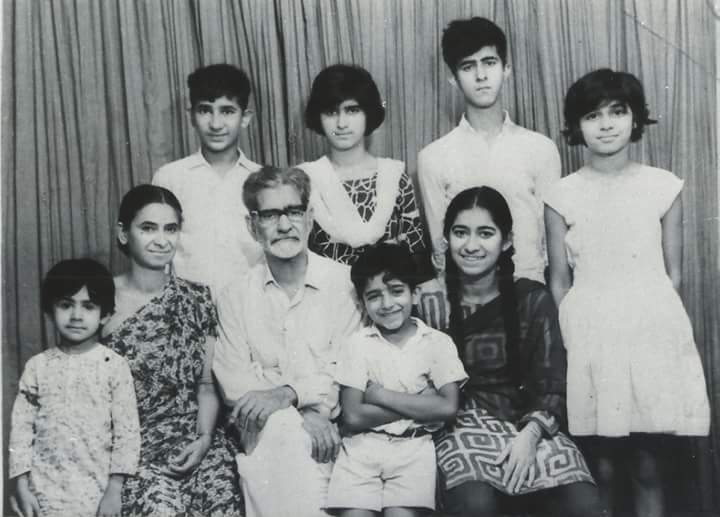

Shabnam: My childhood was extremely interesting because I was born into a family of freedom fighters. And from our childhood, we heard very interesting stories about the whole freedom struggle. And also, because that was the time when German fascism was also defeated by the Soviet Union. So, I heard the stories of both parallelly.

We were exposed to a lot of poetry because my father used to constantly sing Faiz Sahib. And also, there were ‘Mehfils,’ at home, in the late evenings. And I have seen many interesting people like Bhisham Sahni and Habib Tanvir, who were regulars at those parties. But otherwise, our family was economically in very bad shape because, at the time of partition, everyone else went to Pakistan. They were asked to as my grandmother and the three sons, were all party members of the Communist Party India. And Communist Party at that time decided to send all the people who were of Muslim descent or were Muslims to Pakistan to work in Pakistan. But, my father refused to go and we ended up having a difficult life economically.

My parents exposed us to a lot of progressive things. And our house was extremely democratic. So, we grew up in a family where there was access to very good literature and access to very good music. Also, in Delhi, when we were little, my mother sent us to Bal Bhawan, which used to be an extremely vibrant place at that time. So we could do what we liked. I went skating and basketball. My brothers and sisters did various things like clay modelling, dance, photography and so on.

Television came much later. So, all our time after school was spent playing gully-danda and marbles and cricket. My mother was the principal of an NDMC school. So, she had a house on the school premises. And once the school closed for the day all the huge grounds were available to us to play.

And we studied in ordinary government schools. Government schools used to be very good back then. The quality of education was satisfactory. And it is not like now that most people don’t want to send their children to government schools.

And the fact that our house was very democratic and very gender sensitive there was no difference at all between the genders or the roles. So, this was, I think which is what made the basis for our understanding of an equal society, of treating people with dignity and with respect.

FII: How did you start your non-profit NGO activism?

Shabnam: That was an accident. I was studying in the Soviet Union and at that time they had a six-year integrated course. You finish six years and you get an M.A., M.Ed. I had finished three years by then and when I came to Delhi, a friend asked me to help with teaching girls in Nizamuddin Masjid. There was a small centre run by some non-profit. So, I started teaching there.

I was not too happy because I realised that they didn’t want to go beyond just reading, and writing. They only wanted to teach the girls how to read and write and that is enough. Whereas for me, that was not the case. If I was doing something and at a young age you are very idealistic. And also my first students had never been to school. That is something that shocked me.

One of the first students, there were six students when I first went there, was a girl called Farida who was married at 12, and divorced at 15. When I met her for the first time, she was 16 years old with two children. At 16 years of age, she was divorced and had two children. So, after teaching them for two months, I realised that I could not abandon them. And so I took that decision to carry on there. So I ran the centre till 1989.

We managed to educate over 400 girls and many boys. We then later started technical education. Computers were something very new in those times. So, we ran computer classes and electricians classes, tailoring cutting, and all kinds of things apart from education. We helped girls to sit privately from Jamia and IGNOU and appear for 10th and 12th and so on. So, that is how I started.

I don’t remember when I did register an organisation, which was called SEHER. Initially, I was doing it on my own. But then as it expanded, funds were required. Even if you were taking donations, you had to give receipts and all that. So, we formed this small organisation.

Then, in 1989, when my brother was attacked and killed on 1st January, in his memory, the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust was formed, SAHMAT. Safdar always wanted me to help him. You know, he had this dream of starting a theatre repertory. And I had helped him but in between there was a huge program to raise funds for relief work in Bengal. And at that time, I had helped Safdar in coordinating that. So, he realised that I had good organisational capacities. So, he always wanted me to, once he established the repertory, he wanted me to run the logistics part of it. But, that didn’t happen, but after he died, I also felt that I owed that to him.

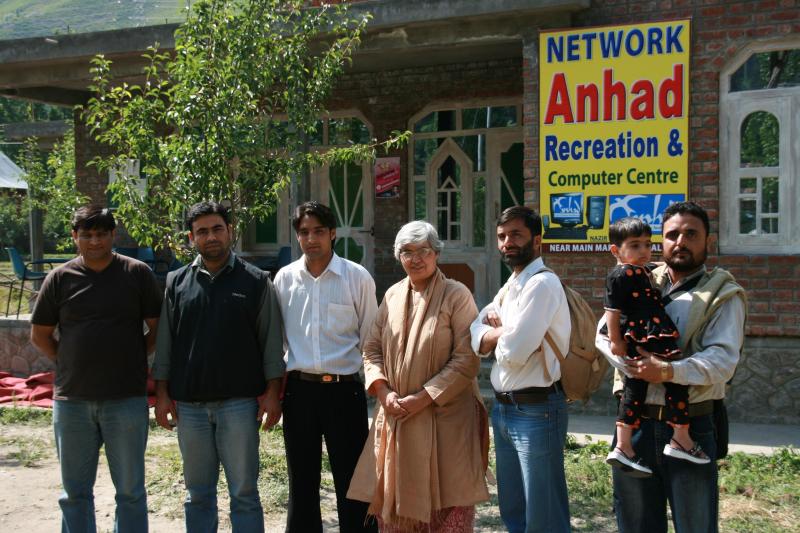

Then I joined SAHMAT and for 15 years, I ran SAHMAT from 1989 till 2003 January. I was running along with a core group of people, but I was the only full-time person there who worked 15-18 hours a day to make things happen. In 2002, I was still in SAHMAT, I went to Gujarat and ended up spending almost a year there. So, during that period, I felt very strongly that SAHMAT was doing very important work, but still, I wanted to do something else. Because SAHMAT was a platform for artists and intellectuals and was mainly confined to big cities, I wanted to move to grassroots work and fight the ideology of hate. So, in 2003, I moved out of SAHMAT in January. And in March, we formed ANHAD with Professor K.N. Panikkar and Harsh Monkar.

FII: What keeps you motivated, especially when the atmosphere in the country is so concerning?

Shabnam: I think the idea of India, which is diverse, which is plural is ingrained into my psyche. And not only me, all five of us. Because that is how we were brought up.

We have to build a society which is equal and what the Constitution also gives us. So, that is a commitment to myself, and everyone around me. That commitment and conviction were always there. Secondly, we were never pressured to run after money. So, that has never been the priority. I barely managed to survive. That was never an idea that take up a job which would give you a lot of money. That was, so as far as those fundamentals were concerned, they were very clear. But I think what is most important is that a lot of people, a lot of people, get courage from ANHAD and our stance in remote areas.

There have been times when we have broken the siege. We have spoken up against the people in power. I remember, if we talk of recent events, the Ayodhya judgment when it came first from Allahabad and then the Supreme Court the government and the RSS had prepared people not to speak out. The Muslim Morcha of the BJP, I am forgetting what it is called, is run by Indresh, they had meetings across India and Bastis telling people to accept whatever comes. However, it was very clear that the judgment would be coming in favour of the Hindutva forces. So nobody was speaking out.

Of course, you know, portals like The Wire and many other people wrote very strong articles. But it was, I think, except for ANHAD, nobody did a public program saying that this is not acceptable to us, even if we cannot change the judgment. So breaking that layer of fear, we have done it many, many times. And because of that, there is a large section of people who look up to ANHAD.

I think one has no option but not to get into depression. If activists like us give up and if we think that things are so bad and nothing can be done, then there is no way we will ever be able to fight this battle or win this battle. We have always maintained and there have been times over the last two, or three years when I called people and said that this is not the end. And we have still not lost the battle. We have to fight. We cannot leave it to political parties alone. We have to be on the ground fighting.

And also the fact that there is no way we can leave this country to the younger generation, to people of your age, in the mess that it is right now. I think that is what keeps not only me going, but a lot of people like me going.

Aruna Roy, Kavita Srivastava, Teesta Setalvad, Apoorvanand or Harsh Vardhan, some so many people are not keeping quiet and constantly raising issues. Because we strongly believe in an India which has a space for everyone and equal dignity for everyone.

FII: How is your organisation ANHAD working towards achieving the goal of communal harmony?

Shabnam: Anhad has done a huge amount of work. We are a 20-year-old organisation. I can tell you what we have done. Right now, our work has shrunk a lot because we have no resources. We lost our FCR in 2015. And most of our funders, Indian funders, were sent income tax notices. Just asking them if they have donated to Anhad. As a result, for the last 9 years, we have been surviving on personal donations. Which vary from 100 rupees to 10,000, 20,000, 25,000. I send out messages on my WhatsApp. So sometime, one month, somebody will give 25,000 and many will give 100 each or 1,000 each. To run an organisation on personal donations is not an easy thing. It is a very daunting task. We can do it because we have people who are committed to the cause.

In the first year, we were organising residential training camps for young people. Our first task was to get people working with various organisations to come and attend these camps. There we talked about everything. From the independence struggle to the constitution of India to globalisation, communalisation, gender, caste, class, and the whole idea of India, Indian identity. It was a mix of realities. It used to be a mix of many different things, along with showing cinema like ‘Dor’ and ‘Naseem’ and ‘Parzania.’

From 2003 to 2012, at least 25,000 people or more attended these camps. This was one of our popular works which we were doing. Apart from that, we were working in colleges, running cinemas, and film clubs, having discussion groups, organising competitions, organising elocution, and painting competitions around the theme of communalism.

Then we organised a large number of cultural programs celebrating our diversity and we organised those in various states, at the national level, and state levels encouraging young artists to come and perform. And a lot of them ended up also making special repertoires for us on non-violence, on communal harmony.

In 2007 one campaign which we called ‘Safeguarding the Indian Constitution’ in Gujarat, covered 600 villages. We had for one month we trained three different teams in street theatre, public speaking, politics, and understanding, and we made posters and exhibitions, we printed one lakh copies of the preamble of the constitution and then we travelled for a month. Going from village to village, performing, doing public meetings.

During the UPA regime, we intervened quite a lot at the policy level. I was part of the 5-year plan in several committees. And then, apart from this, we had workshops on gender. We were present in 50 villages: 30 in Kashmir, 10-11 in Bihar and about 10 villages in Mewat area.

We went to Kashmir after the earthquake to do relief work with Telgar. Then we moved on to livelihood support. And then we expanded to villages where we started youth clubs and libraries, reading rooms, women, you know, centres and so on. This is how we expanded in Bihar also. We went there after the Kosi floods, in 2008. And then we expanded in villages.

FII: “The religious and communal divide in the private sphere indirectly impacts the public sphere.” What is your take on this?

Shabnam: At a personal level, the kind of divide that we see today, even in 1992 when Babri Mosque was demolished, there were a lot of things in the public sphere, but privately, this kind of hatred was not there. Hatred was there, but not this deep. It’s only when politicians start using religion and propagating hatred that it seeps into private life. Otherwise, a majority of the people in India are religious. There are very few per cent like us who are agnostics or atheists. But people have lived together in this country. They have worked together and lived together.

The interview has been paraphrased and condensed for clarity