Trigger Warning: Child rape

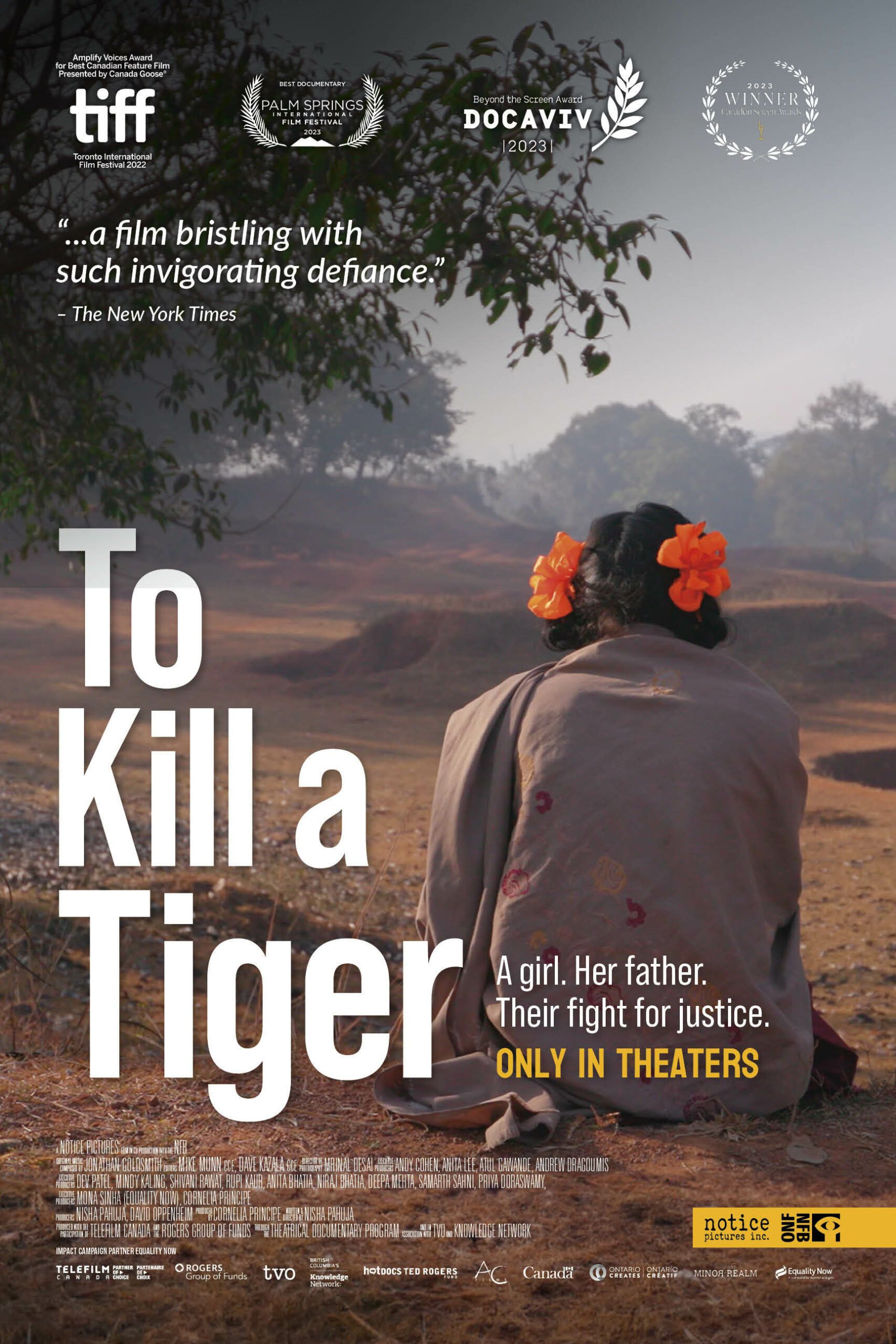

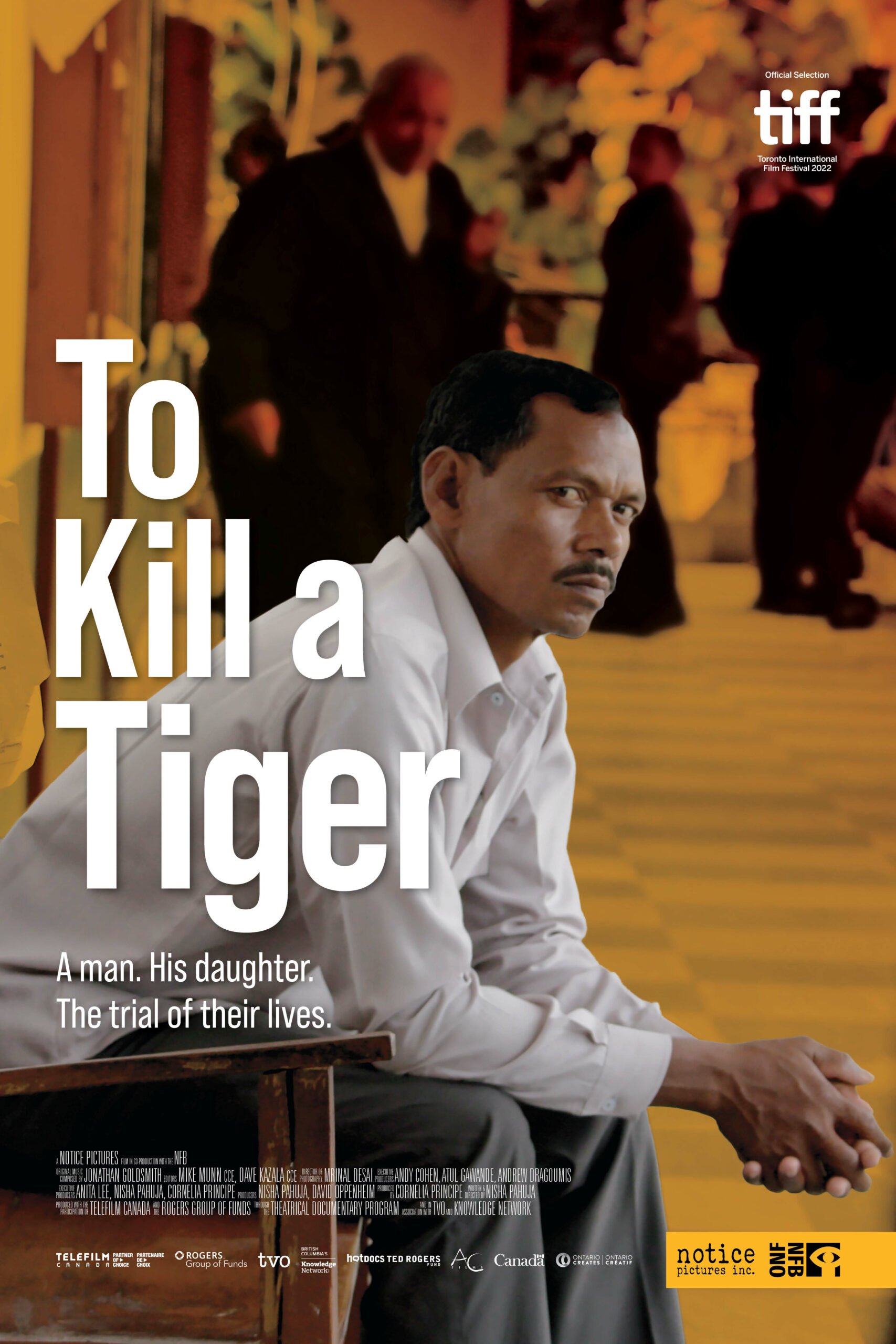

Nisha Pahuja’s 2024 Oscar nominated documentary To Kill a Tiger tracks the fight of a 13-year-old survivor of a violent gang rape in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand to bring her rapists before the law and get them convicted for their crimes. In her efforts, Kiran, as the survivor is named in the film (not her real name), is supported by her father Ranjit who is in turn aided by a local NGO, Srijan Foundation, who helps the family navigate the legal and bureaucratic labyrinth of rape and sexual assault cases in India. Indeed, the film is received in the West as the story of an ‘Indian father who stood up for his daughter’ rather than abandon her, or worse, murder her to preserve the family honour, the dominant narrative about fathers, daughters and rape in the South Asian diasporic context in the eyes of the world.

Both parents—fathers and mothers—should be encouraged and empowered to protect and stand by their minor daughters and sons in cases of rape and sexual assault, not just fathers.

While it is no doubt commendable that Ranjit stands by his daughter, and more men should be encouraged to do the same, it is not enough just to spotlight the father’s resolve and conviction. Both parents—fathers and mothers—should be encouraged and empowered to protect and stand by their minor daughters and sons in cases of rape and sexual assault, not just fathers. The gang rape endured by the 13-year-old Kiran could have easily happened to a child without a father, with an incapacitated father, or no male guardian at all. Would Kiran’s mother be empowered to come forward and stand up for her daughter? If not, what would it take for Kiran’s mother to go to court to get justice for the minor child under her care?

That, intentionally or unintentionally, women become proxies for patriarchy is a well-known fact, one that Pahuja herself has explored in a subtle but powerful manner in her first documentary film The World Before Her (2012). To Kill a Tiger, however, stops just short of exploring what would have happened to Kiran if the father was unwilling: would Jaganti, Kiran’s mother have persisted on her daughter’s behalf? To Kill a Tiger does not ask this question. Its absence creates a haunting deficit at the center of the film that the father’s determination does not mitigate.

The story behind To Kill a Tiger

The incident at the center of the film took place in 2017 in the village of Bero in Jharkhand. Three men raped the 13-year-old Kiran at a relative’s house where the family had gone to attend a wedding. Though the village tried to pressurise Ranjit to let Kiran marry one of the rapists, on behalf of Kiran, her father decided to press charges against the three men, including a nephew, one of the rapists.

Pahuja, a Canadian Indian documentary filmmaker was in India in 2017 working on a documentary about NGOs conducting gender sensitisation training for men in rural India. Pahuja came across the case while tracking the work of Srijan Foundation, the NGO that helped Kiran’s family with the case. Through the NGO, Pahuja and her team gained the trust of the family and permission to film the case.

The survivor Kiran, now twenty-one years old and studying to become a police officer, gave permission to the filmmakers to show her face and her identity in To Kill a Tiger, even though under POCSO laws in India, the identity of minors in rape and sexual assault cases must be kept anonymous.

The film itself took seven years to complete. The survivor Kiran, now twenty-one years old and studying to become a police officer, gave permission to the filmmakers to show her face and her identity in To Kill a Tiger, even though under POCSO laws in India, the identity of minors in rape and sexual assault cases must be kept anonymous. To Kill a Tiger currently streaming on Netflix makes a pointed appeal at the start not to reproduce or circulate images of the survivor outside the viewing of the film which is followed in this review.

The daughter, the father, and the sidelined mother

The film’s main narrative opens with the footage of a 13-year-old Kiran in her house getting ready for school. She is seated at a mirror combing her hair, braiding it. Against a close-up of Kiran’s fingers making an intricate, orange-colored bow for her braids, we hear her father Ranjit’s recollection of the day of her birth, the happiness of getting a daughter, in a voiceover. This scene prepares us to see the film events from Ranjit’s point of view, a perspective deeply empathetic towards his daughter, but also at times ambivalent about the court case.

The documentary follows the actions of the family and the NGO as they navigate the local government, regional government, and finally, the high court in the capital city of Ranchi, where the trial will be held. While the narrative of To Kill a Tiger privileges the thoughts, words and actions of Ranjit, the most memorable scenes spotlight Kiran, the 13-year-old survivor with a soft voice, clear eyes, and steely resolve, as she speaks to the camera about whether she did something to invite this attack, how she will disclose the details of the rape to a future husband, and preparing for the trial with the NGO and the prosecutor.

These scenes in To Kill a Tiger offer a powerful portrait of rural India where the patriarchal grip on the “traditional” way of life appears to be weakening against an irresistible wave of change coming for them with young girls leading the change. The few young men of the village shown riding around in motorbikes aimlessly and staring with hostility at the film crew appear not to be part of this change.

Jaganti, Kiran’s mother, appears to be a cypher in To Kill a Tiger. She uses her voice, but her character and agency are left undeveloped.

Jaganti, Kiran’s mother, appears to be a cypher in To Kill a Tiger. She uses her voice, but her character and agency are left undeveloped. When the village Mukhya argues that the rape is an ‘internal village matter’ that should be settled in the village without going to the police, Jaganti pointedly interrupts Ranjit and the Mukhya: ‘The thing is that they have already killed a woman after accusing her of being a witch. And that was not true. It depends on whether you want to believe it or not. But they called her a witch and took her into the jungle and killed her. And now they go and do this.’ But that is the end of her role in the film.

To Kill a Tiger: placating the patriarchy vs feminist solidarity

This refusal to engage the mother and frame the film exclusively in terms of a father fighting for his daughter appears at times to be placating the patriarchy. An NGO representative in the film speaks about the need to educate men about sexual violence, since empowering women and girls alone has not curbed crimes against women in India. While educating men and boys how not to rape is an important piece in mitigating sexual violence, this shift in the site of empowerment from women and girls to men and boys appears counter intuitive.

Women and girls are the largest and the specific target demographic of sexual violence in India. Countering sexual violence through robust neoliberal individual agency, or male consciousness-raising might be an aid to mitigate sexual violence. But, as a societal crime, only solidarity and empowerment of women as a group will establish the required cultural change to redress gender-specific crimes against women. For this to happen, the feminist work of empowering women and girls needs to go on.

It is instructive that towards the end of To Kill a Tiger, Ranjit tells the interviewer following the successful outcome of the trial, ‘They told me you cannot kill a tiger by yourself. But I proved to them that I can kill a tiger by myself.’ This framing of securing justice for three violent predators as his individual accomplishment is categorically different from Jaganti’s earlier awareness that in the same village they had killed women by accusing them of being witches.

This is true feminist awareness, that the same dangerous and outmoded beliefs that killed a woman by calling her a witch also normalises seeing women and girls as targets of sexual violence. The mother has this awareness; the father does not.

To Kill a Tiger tells a complex and engrossing story of resilience and justice in rural India. Pahuja, whose earlier film The World Before Her had contrasted the worlds of young women working in the Miss India pageant and those working in the Hindu fundamentalist organisation Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s Durga Vahini training camps, has a gift for getting young girls and women to open up to her and speak their thoughts. She is also equally talented at getting both bigoted and patriarchal men, like the father of the Durga Vahini lieutenant in the earlier film, and mild-mannered men like Ranjit in this film, to speak to her as well. It remains to see if Pahuja is interested in having the mothers speak to her about their lives and experiences as well. Both of Pahuja’s documentaries on women’s and gender issues have so far skipped the mothers, while inviting fathers and daughters to speak.