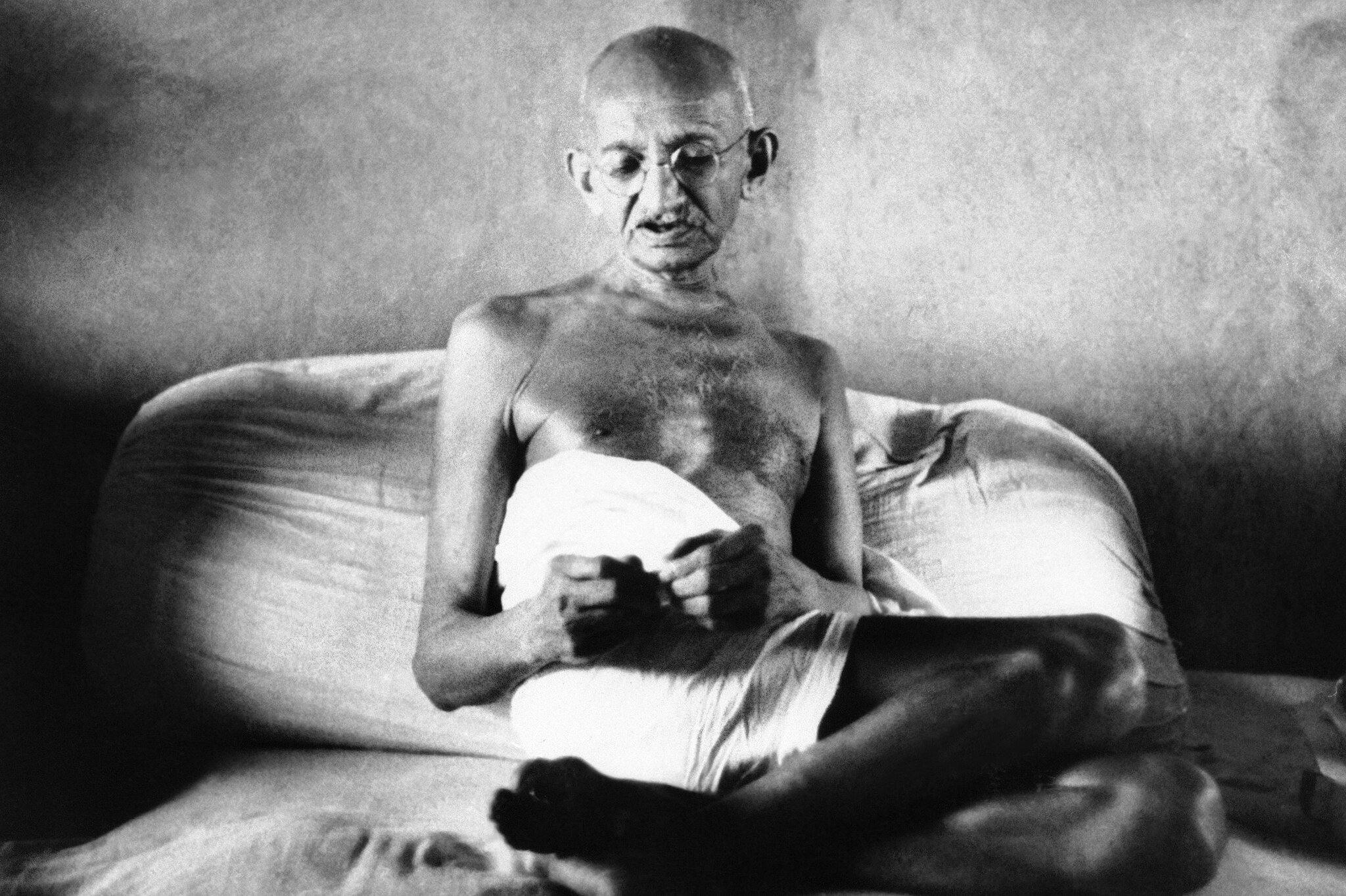

All over the world, India seems to be almost unequivocally synonymous with Gandhi and his philosophy, despite the fact that there were several views that contested Gandhi’s notions of ahimsa (non-violence) and his perceptions of satya (truth), a truth that sometimes alienates the oppressed. Even within India, Gandhi’s codes are often religiously followed with a degree of almost inflexible adherence. Children often invoke Gandhi’s name as one would a prophet’s. Some primary schools have a course on Gandhian Values in lieu of a course on moral instruction where they teach children about Gandhi’s life, not as a philosophy, but as a doctrine delineating the rights and wrongs of human behaviour.

Even within India, Gandhi’s codes are often religiously followed with a degree of almost inflexible adherence.

However, this is not to imply that Gandhi’s philosophy remains uncontested within the country. These contestations arise from highly polarized factions, with the loudest voices in contemporary times often coming from Godse-apologists espousing far-right Hindutva ideology. Criticism also comes from the far-left, although their immediate concerns have less to do with problematising Gandhi and more to do with the problematics of the here and now. After all, it might get confusing if both wings try to rewrite the past at the same time.

Despite all critique, Gandhi’s views serve as an effective center to the current conflictual positions in the nation, with respect to which one can gauge one’s own position. And if Gandhi’s political philosophy is to be considered a point of reference for all other political thought, then one must analyse his position on most things that are still relevant. It is unfortunate that the concerns of the past remain the concerns of the present.

Despite all critique, Gandhi’s views serve as an effective center to the current conflictual positions in the nation, with respect to which one can gauge one’s own position.

It does not bode well for the suggestion that we have made any progress as a country that we still continue to discuss the same things that we were discussing under a colonial regime – be it religious divide, sedition, gender, or caste (although there is a tendency to invisibilise caste and treat it as a non-issue when it still very much remains pervasive). This article will focus on Gandhi’s views on gender and how they, as some of the most revered views on this aspect, have shaped our history and our present, and perhaps our future.

Gandhi’s innateness dilemma

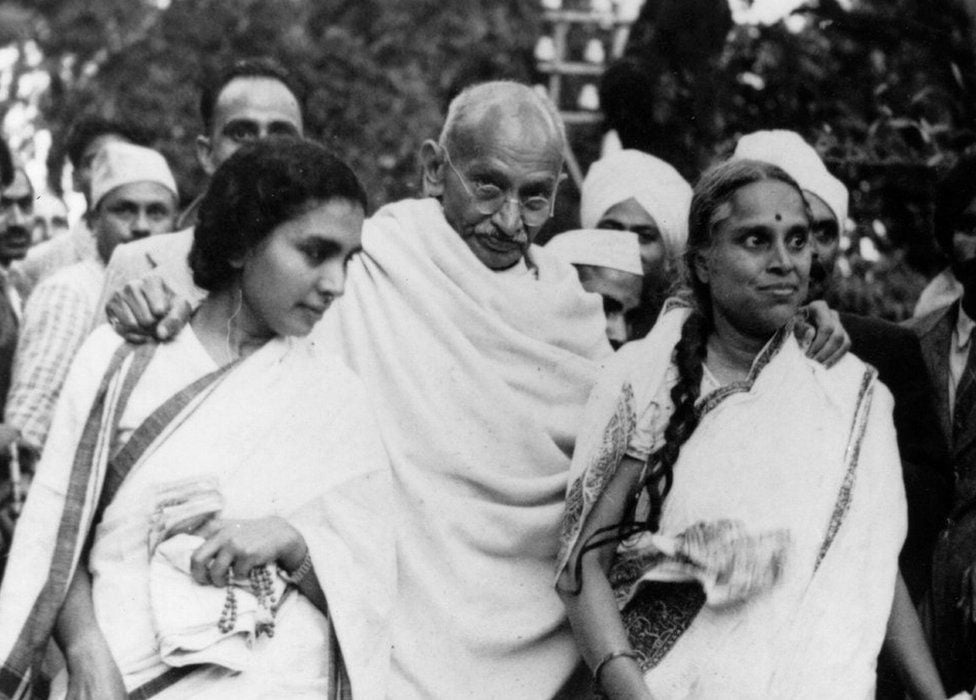

Gandhi’s model of non-violence had gendered leanings in that he often sought to posit women as the model of non-violent restraint. An article on Gandhi’s opinions on women’s role in the freedom struggle states:

‘it is in their innate nature to be passive. Thus they of all people, would be able to successfully follow the path of non-violence, and it would behoove men to emulate their great strength.‘

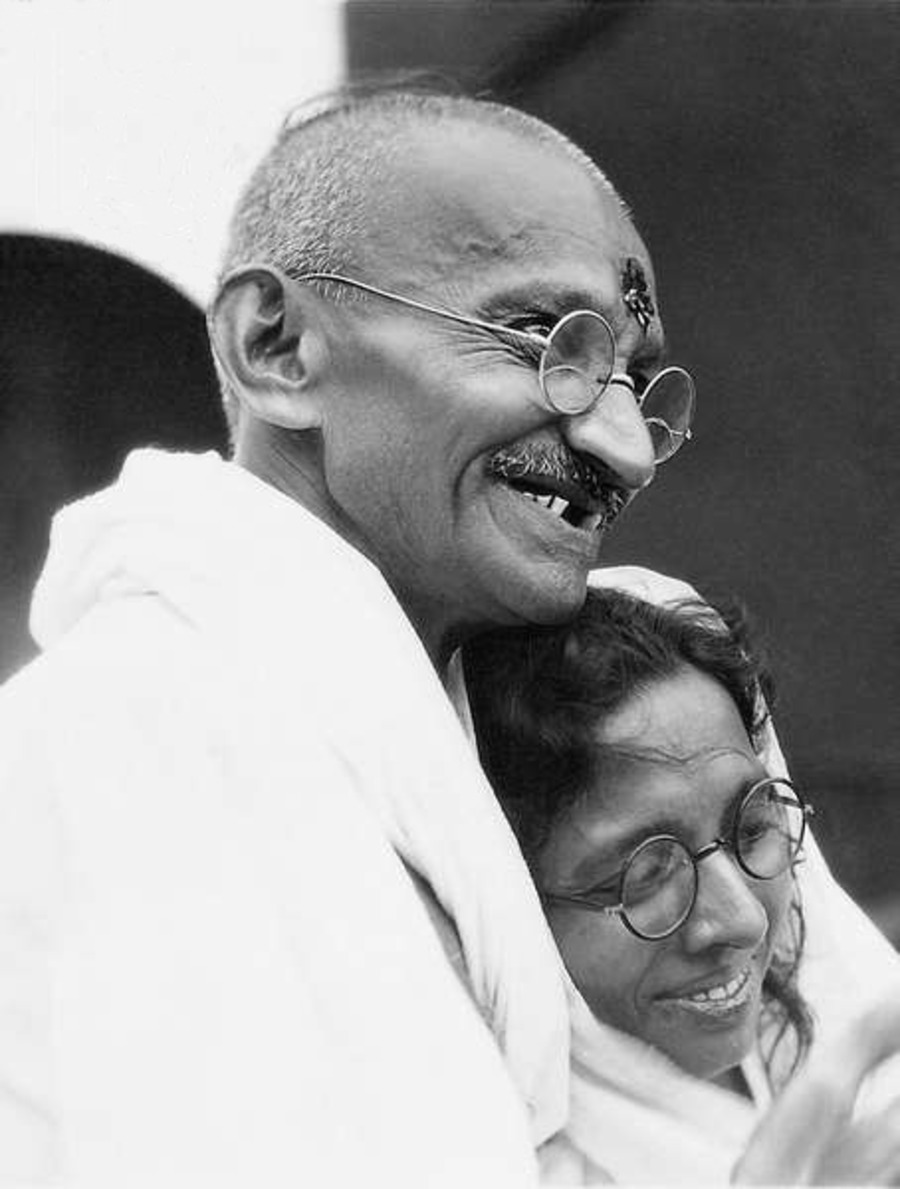

This view also, in turn, served to back up his rhetoric in support of a completely non-violent struggle. Women being completely passive, he claimed, would be left alienated in armed rebellion, and a non-violent struggle was a means to make sure that they could not only participate in the seminal series of events that was the freedom struggle but also be an example for men to follow.

This assumption of women’s ‘innate passivity‘ no longer stands scrutiny when one considers the fact that gender is essentially performativity. A lot of this passivity may not have been innate and may have been demanded by their circumstances of existence. This serves to glorify subordination to men and to somehow claim that this innateness is not only true but also essential. It also claims that men can rise above the failings of their gender but women are not capable of that, sequestering women to certain roles while men take on everything that they would like.

Gandhi’s model of non-violence had gendered leanings in that he often sought to posit women as the model of non-violent restraint.

‘One of the limitations of Gandhi’s thinking … was that he sought to change not so much the material condition of women as their ‘moral’ condition. … He failed to put an economic content into his concept for emancipation. Gandhi failed to realise that, among other things, oppression is not an abstract moral condition, but a social and historical experience related to production relations. He tried changing women’s position without either transforming their relation to the outer world of production or the inner world of family, sexuality and reproduction,’ an article by Madhu Kishwar states.

Indeed, this assumption of innateness often extends to Gandhi’s claims about other identities that are a result of the accident of birth – caste, for instance. His insistence on the vitality of the jobs that Dalits performed and thus the apathy to the restrictions that caste placed on opportunities for change was often tone-deaf in the sense that it did not allow social or economic mobility.

The narrative of history

Despite Gandhi’s claims that a non-violent struggle would center around women and their “innate” traits – those of passivity and resilience in the face of tyranny, there do not seem to be a lot of women inducted into the historical canon of the freedom struggle. Most sources only name the same ten to fifteen women These women, with a few exceptions here and there, do not seem to have enough resources documenting their political philosophy, often positing them as subsidiaries to the men that they were associated with – be it Durgawati Devi who is best known for helping Bhagat Singh escape unidentified after he assassinated John Saunders – or Pritilata Waddedar who was part of the revolutionary group led by Surya Sen – or Kasturba Gandhi of whose vision and thought little is known since it is often wrapped around MK Gandhi’s.

‘Just as in his early years he kept insisting that he was a loyal citizen of the British Empire even while objectively cutting at the roots of British imperialism, so also he could keep in harping on women’s real sphere of activity being the home even while actively creating conditions which could help her break the shackles of domesticity,’ says Madhu Kishwar.

Gandhi’s insistence on the domestic roles of women may not ultimately have stopped them from breaking free of the sphere of the private. After all one of the reasons Godse cites for assassinating Gandhi is the fact that he brought the ‘purdah-clad home-bound women into the folds of the freedom struggle‘. But this passive participation made sure that it was only the men, largely, who featured in our history books – whose political thought is considered worthy of analysis and retrospection.

The voyage out

Gandhi’s political ideology had several loopholes and questionable notions of gender roles and identity and we see the consequences of that today. Not only were those in the canon of important figures in the freedom struggle mostly men, they were also mostly upper caste and upper class. History has invisibilised contributions of women, shrouded them in political discourses in favour of men and sought their involvement while also largely silencing them.

The percentage of female representation in the Lok Sabha today is a dismal fifteen percent. These women are following a rich legacy scantily recorded, since women have always stood for the cause of national justice – be it the movement against the Simon Commission nearly a century ago – or the more recent movement at Shaheen Bagh – women have always been significantly involved in the process of building and sustaining a nation and it is safe to say that we would have no nation without its now estranged mothers.

About the author(s)

Adrita Bhattacharya is a Computer Science graduate from Vellore Institute of Technology and is currently pursuing a degree in English and Cultural Studies at Christ University. She has a keen interest in Linguistics, Gender Studies, and Digital Humanities.