When we think of Punjab, either the images of huge, bulky men ready to fight for their motherland or the famous folktales of love strike our imagination. Punjabi literature can immerse both opposites, love and war, into it in the most exquisite way. Where the literature about the wars serves as resistance to invaders or authorities, love is also very militant. History has been witness to the fact that more than anything, those in power fear love.

Whenever we think of Punjabi literature about love, the tale of Heer Ranjha comes to our head. However, the rich tapestry of Punjabi folktales has more underrated love stories that often go unnoticed. For example, the tragic folktales of Sohni-Mahiwal and Sassi-Punnu have been passed from generation to generation for so long by mouth. Reflecting the power that love holds, these love stories serve as an opposition to the patriarchal structure of society, questioning gender norms and the institution of marriage.

Sohni-Mahiwal

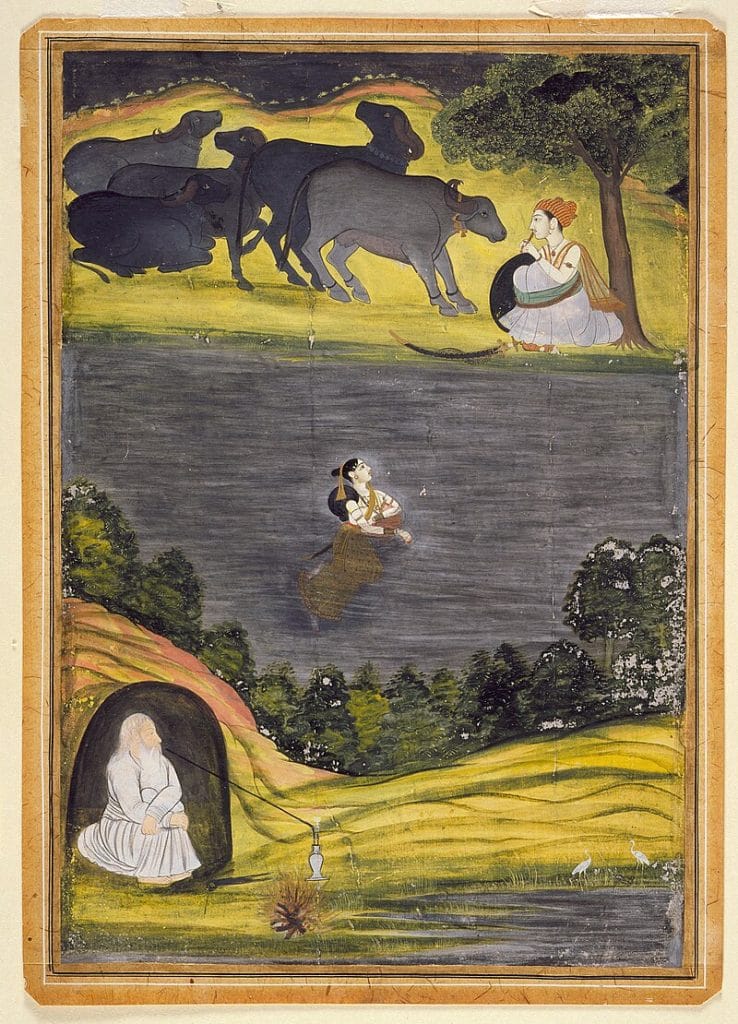

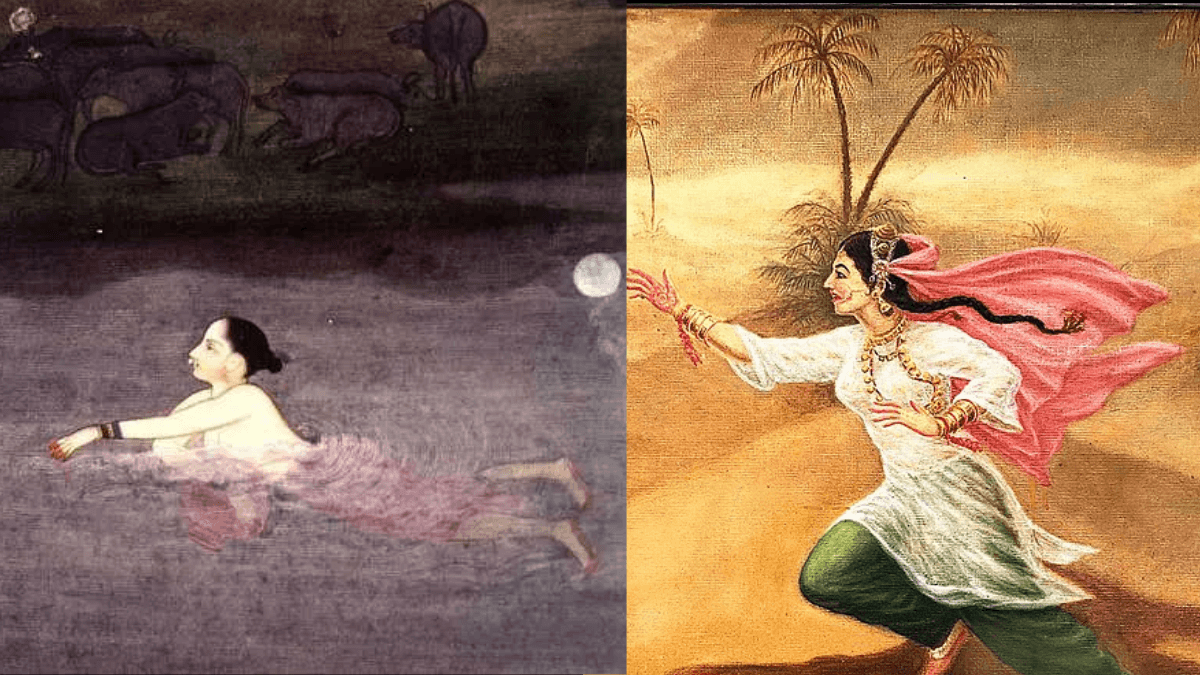

Par Chanaa De, the famous song on Coke Studio, is about the tale of Sohni and Mahiwal, the love story grown in the heart of Chenab. Every night, Sohni used to hang on to an earthen pot and cross the river of Chenab, moving against the waves of water to meet her beloved Mahiwal. One day, Sohni’s sister-in-law replaced her earthen pot with a half-baked pot, which ultimately led to the tragic end of Sohni-Mahiwal’s love story.

In Sufi tradition, there is a symbolic meaning attached to Sohni, half-baked pot, and Mahiwal. Sohni represents the one who embarks on a spiritual journey, the one who has a yearning to be one with the ultimate reality, or God. Since the matka used to help Sohni cross the powerful waves of Chenab or the difficulties in spiritual journey, it represents the correct guidance one needs to be one with God. The half-baked matka represents the unpreparedness of Sohni. The half-baked matka, or lack of preparation, leads to Sohni’s end.

On the other hand, Mahiwal represents the god or the divine. Sohni’s yearning to meet Mahiwal is similar to the yearning of a devotee to meet his God. There is a common feature in Punjabi folklore: death only promises the union of God and the devotee.

Gender roles and the tale of Sohni and Mahiwal

When one reads through the story of Sohni and Mahiwal, it is not this deep Sufi symbolism that springs to one’s head but rather the feminist nature of the literature. Throughout, Sohni defies the traditional gender roles assigned to women and exerts her agency. Unlike other tales, it is not the hero but Sohni herself who crosses the Chenab, the river of love, every night to meet her beloved. Here, Sohni is not saved by the hero, but she used to put her life at stake every day to just spend some time with Mahiwal.

Another time when Sohni defies social expectations is when she chooses the time of night to meet Mahiwal. To control women, nighttime is considered not an appropriate time to get out. Sohni used to meet Mahiwal in the night by crashing against the strong waves of Chenab.

The institution of marriage

Emma Goldman, in her essay, “Marriage and Love,” says, “If the world is ever to give birth to true companionship and oneness, not marriage, but love will be the parent.” Similarly, in the story, unlike patriarchy, marriage is not given much importance. It is not considered a sacred institution. When Sohni was married to another potter against her wishes, she chose to not accept it as the end of her life. Marriage was not the end goal of her life; for her, without love, marriage was useless.

Moreover, every night she used to go to meet Mahiwal despite being married, showing her denial of accepting the institution of marriage.

Sassi-Punnu

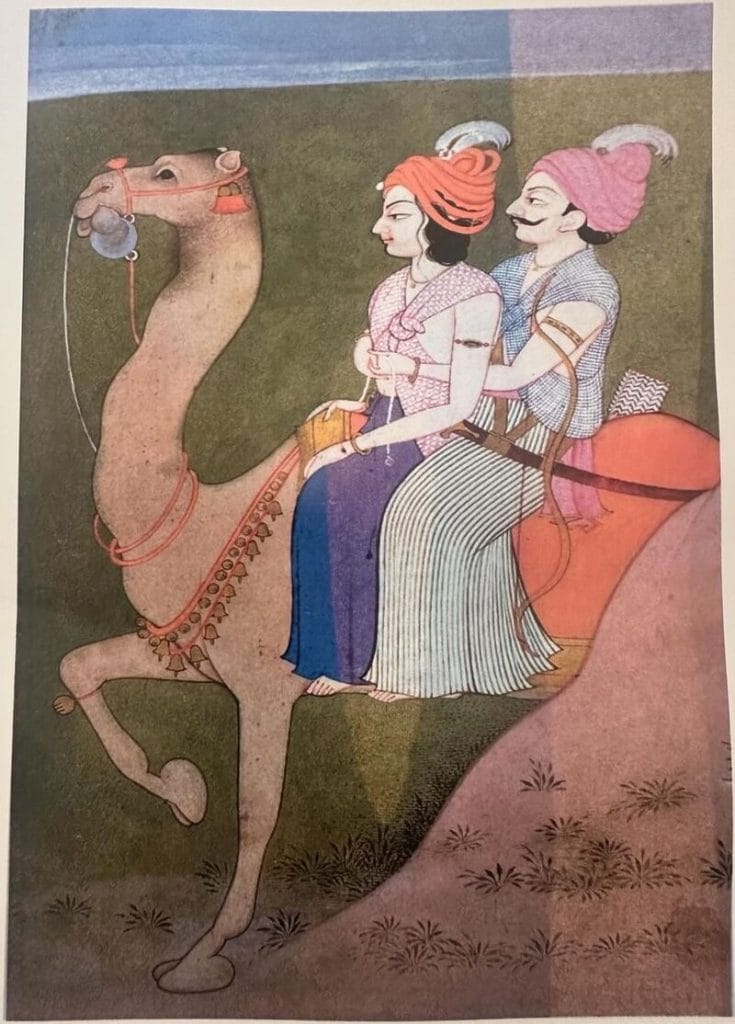

When the celebrations of Sassi and Punnu’s marriage were going on, Punnu’s brothers intoxicated him, put him on the back of a camel, and, at night, took him back to their hometown. Sassi’s pain is very well expressed in a Punjabi song titled “Sassi Punnu” by Prof. Ravneet Kaur. As Sassi ran looking for her beloved, she met a shepherd. Sassi was thirsty; therefore, she asked the shepherd for his goats’ milk. The man helped her but also tried to harass her. Sassi prayed to God to help her retain her honour. Her prayers were heard, and the ground beneath her split open, leaving only an end of her ‘dupatta’ as a trace of her above the ground.

The 1983 film Sassi Punnu, directed by Satish Bhakhri, is also based on this tragic folk tale of Sassi and Punnu. This folktale also reflects the deeply rooted misogyny in our minds and the consequences women have to face when they oppose societal norms.

Sassi: The not-so-honourable woman

As per the legend, Sassi was born in the house of the king of Bhambore in Sind. When she was born, the astrologers predicted that she would taint the name of royalty. Thus, the newborn was put in a wooden casket and set afloat on the river Sindhu. The box was found by a washerman in the kingdom who adopted and raised the child.

This incident reflects the deeply entrenched notion that women should be controlled since they are the honour of the family. If women cross the line that is made by the patriarchs, she would taint the honour of the family. This burden of honour is another way to control women from exerting their agency.

When Sassi asks the shepherd to quench her thirst, he tries to take advantage of her, showing how a woman without a man is considered an object that has no will of her own.

The oral literature of Sohni-Mahiwal and Sassi-Punnu is still told in Punjabi households to emphasise how only death can assure the ultimate union of the lovers. Moreover, the telling and retelling of these stories can ignite more feminist conversations amongst people.

References:

- https://scroll.in/article/849924/heer-ranjha-and-sohni-mahiwal-the-love-legends-from-punjab-that-turned-gender-roles-on-their-head

- https://khalsavox.com/heritage/sassi-punnu-the-tragic-folk-tale-of-eternal-love/

- https://hindi.webdunia.com/love-stories/sohni-mahiwal-love-story-hindi-116121500025_1.html

About the author(s)

Jatin Chahar (he/they) is a student of Philosophy at Ramjas College, University of Delhi. His writing stems from critical reflection on various socio-political issues, particularly gender and politics. Art is resistance for him. He loves making art that serves the masses and brings forward the realities of the power structure of contemporary societies which excludes marginalised sections of society. He is also into photography and filmmaking. His major areas of research interest are caste, class, and their intersection with sexual fantasies.

Such an interesting read! Punjab’s folk culture is much more than its present popular image.