Feminism and climate justice in India spell an urgent call for gender-neutral engagements with climate change whilst celebrating, at the same time, the transformative roles that women play in environmental advocacy. Gender and environment do not exist in a vacuum. This mainly discriminates against women, especially the marginalised, since women rely more intensively on these natural resources to support their livelihoods and manage vital resources including water, food, and energy in the household. With the increased frequency of climate shocks in the form of droughts, floods, and erratic monsoons, women bear greater burdens-from walking further distances to collect water or firewood to managing economic precarity as small-scale farmers without secure land rights. The dearth of basic education and health services along with capital, in general, has complicated these particular issues.

However, such cultural norms inhibit women’s participation in decision-making even in households or communities. It is among these structural vulnerabilities that Indian women have emerged as key change agents fighting environmental justice. Resilience, innovation, and leadership are a few among many characteristics which exemplify the struggle at just this time against the multifaceted impacts of climate change. Among other examples, one that stands out quite particularly among instances of women-led environmental activism is the Chipko Movement during the 1970s, which involved hugging trees by women belonging to the Himalayan region of Uttarakhand to prevent felling of trees in their areas, prohibiting the loss further to their livelihood. It saved vast tracts of forests but triggered a global debate on environmental ethics and community rights associated with the deep-rooted connection of women with nature.

Fast-forward to today and grassroots leadership is provided by women from all over India tapping into traditional ecological knowledge and rearticulating it into modern contexts. For example, the women of the Niyamgiri Hills of Odisha have agitated militantly against mining projects that threaten the forests and means of living in their midst. In doing so, they assert the coincidence of environmental and indigenous rights.

Analogously, the self-help groups of women of Maharashtra’s drought-prone districts have organised at the grassroots to build check dams and implement methods of watershed management. Women fishers along India’s coasts criticise industrialised practices but are committed to sustainable fishing practices and also resist large-scale development projects threatening ecosystems and communities. These cases indicate how the leadership by women in the grassroots sector is not only transformational but also vital in instilling resilience and sustainability.

Gender-sensitive disaster response

Equal education and capacity are building to equip women with the knowledge and understanding of the myriad issues of climate change. Women’s programs in climate literacy can make them understand other environmental issues and prepare them to adapt to certain practices in agriculture, water management, as well as renewable energy. Skill training in recently emerged areas like solar energy installation and sustainable construction can provide women with alternative livelihood options and reduce their vulnerability to climate-related economic shocks.

Finally, all government partnerships with NGOs and women’s organisations can broaden the impact of community interventions. Such collaboration can facilitate knowledge sharing, resource allocation, and best practices, which make localised interventions scalable and inclusive. For instance, NGOs working with women’s cooperatives have implemented biogas programs that easily eliminate the use of firewood, improving air quality while also providing some of the money generated to women for income.

Climate justice also wants disaster management plans to account for the needs of women and children because they are usually the worst affected by disasters. This means access to sanitation facilities, health services, and safe spaces after climate-related disasters. It is a giant leap in reducing risks to women as it can make a community stronger as a whole. This brings us to the conclusion that the coming together of feminism and climate justice represents a transformative approach to redressing the unequal impacts of climate change and giving recognition to women as drivers for sustainable change. Putting women at the centre of climatic resilience efforts can help not only mitigate the gendered impacts of environmental degradation but unlock the full potential of women as leaders, innovators, and advocates of a sustainable future; through their stories of resistance, resilience, and creativity, it shows just how transformative feminist environmental advocacy can be in an existential crisis.

Climate justice in India calls for systemic change: be it a shift in resource allocation and governance structures or increased gender equity in education, employment, and policy-making. The moment the climate crisis worsens, advocacy for women becomes more a question of survival than just one of justice. It is through the recognising and amplification of contributions that such a world can be built, more just and resilient, in which voices most affected take leading roles in implementing solutions to address climate change.

Eventually, feminism and climate justice would become a transformative road to address the unequal impacts of climate change, out of which women come to play an important role as powerhouses for sustainable innovation.

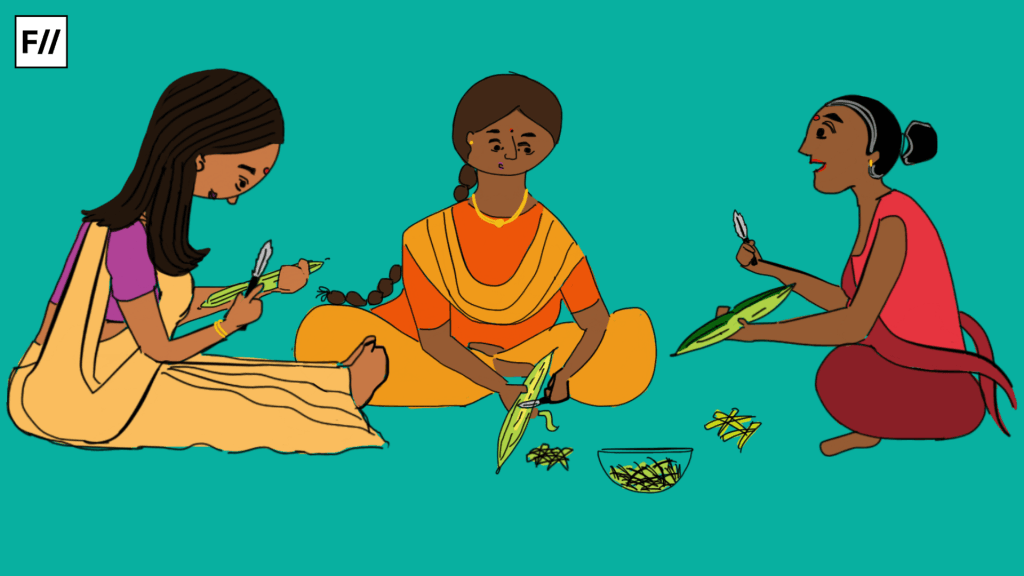

Women and sustainable practices: A localised approach

Apart from activism, women stand at the forefront of sustainable practices that are combating climate vulnerabilities while ensuring the well-being of people. For instance, in Gujarat, women revived the traditional stepwell water-harvesting systems so that people could access water during drought years. In Andhra Pradesh, women farmers were among the pioneering users of climate-resilient agriculture, like zero-budget natural farming, that reduced reliance on chemical inputs, increased soil fertility, and had a minimum adverse impact on the environment.

Such initiatives indicate that women’s knowledge of local ecosystems and resource management is a strong tool in the fight against climate change and achieving sustainable development. It is true, however, that these contributions have hardly been reflected in climate governance and policy decisions wherein women’s voices are highly underrepresented. There is a need for an intersectional approach to appreciate the myriad forms in which gender intersects with class, caste, and ethnicity that together shape climate vulnerabilities and responses.

The policies have to be directed at redressing social inequalities and including women at all levels of decision-making, from panchayats at the local stage to the national climate strategy. To strengthen women’s responsive capacities for climate adaptation and mitigation, it is vital to empower them through land ownership, credit, and technology. Acquiring land titles, for instance, grants women economic independence and supports the adoption of environmentally friendly agricultural practices at the local and global levels. Such initiatives are, for instance, financial inclusion programs like the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), which also prove that access to credit and training for women can help withstand climate adversities while improving their livelihood.

Redefining narratives for a just climate future

Bringing women to the centre of efforts in climate resilience, India mitigates the gendered impacts of environmental degradation and unlocks the full potential of women as leaders, innovators, and advocates for a sustainable future. Inspiring testimony of the power of feminist environmental advocacy in challenging an existential crisis are their stories of resistance, survival, and creativity. For climate justice in India, It is collective activism from various ranks that hammers the road to climate justice.

National programming at the grassroots level- having women access to education, credit, and land rights builds a resilient ground for innovation. Policy-wise, integrating gender perspectives into national and global climate strategies is an imperative requirement. On the policy-making side, it would also be much more important to integrate gender perspectives into national and global climate strategies. The policymakers in India need to understand that women play an important role in climate adaptation and mitigation and go beyond tokenistic representation to ensure that women represent a large chunk of decision-makers. That will make the strategy of climate action not only fairer but more effective as it taps into the diverse experiences and insights of those who are most impacted by environmental change.

Stories of Indian women leaders of environmental movements – from rural farmers adopting innovative agricultural techniques to urban activists demanding cleaner air and policies for renewable energy – represent much wider prospects for feminist environmentalism. These women are not only adjusting to climate challenges but are proactively restructuring narratives and systems to make a more inclusive and resilient society. If these voices are amplified and systemic barriers begin to crumble, with resources and opportunity more equitably arranged, India has the chance of breaking open this doorway into an idealised living and breathing version of a just climate. For that journey- commitment, cooperation, courage -there indeed lies the brightest, most durable promise for it.