‘Punjabi Aa Gaye Oye!’

With actor-singer Diljit Dosanjh selling out stadiums and filling arenas to the brim, one can successfully concur with the aforementioned statement uttered by the singer. In his now-viral video from a concert, Dosanjh, who began his career in the Punjabi film industry, shared the kind of struggles that he had to face as a performer practicing the Sikh faith. From making fashionable outfit choices to featuring in mainstream Bollywood films, the actor spoke about how the struggles due to his identity persisted wherever he went.

“Pehla kehnde si sardar banda fashion ni kar sakda. Main keya main ta karke dikhau. Fir kehnde si sardar banda filma vich ni aa sakda. Main keya main ta karke dikhau.”

Ultimately, of course, Dosanjh broke through the shackles and has arguably emerged as one of the biggest performers from the Sikh faith.

Dosanjh’s arrival into the mainstream and global pop-culture scene has inspired countless youth donning turbans who finally see a fragment of themselves on screen. His arrival seems to have made it ‘cool,’ to be a Sikh artist, given the numbers his films and songs yield nowadays. On April 27, 2024, Vancouver’s BC Place Stadium saw Dosanjh script history by hosting the largest Punjabi concert outside of India, with about 54,000 fans in attendance. While Dosanjh is arguably one of the biggest entertainers from the faith, previously, Bollywood has seen the Sikh faith in different films, some even centred solely around the faith, like Singh Is Kinng (2008), Singh Is Bliing (2015), and A Flying Jatt (2016). The representation of Sikhs, however, has always remained questionable, with roles often viewing the men of the faith as scholar Anjali Gera Roy argues as ‘uncouth rustics,’ or as ‘comic elements,’ supporting the film.

Much has been seen, said, and debated about the representation of the men of the faith. There appears to be a void both in terms of representation and discussion when it comes to the women of the faith. As many scholars, like Laura Mulvey, have argued in the past, women are often represented in cinema through the male gaze.

Parvinder Mehta argues in her book, “Imagining Sikhs“(2013), how Sikhs in Bollywood, who she refers to as ‘Bolly Sikhs,’ are represented through a ‘predominant,’ and ‘controlling gaze.’ Mehta argues that Sikhs remain ‘marginalised in difference,’ and acknowledged only through a Hindu-centric lens of approval. Hence, Sikh characters donning turbans often remain displaced from their original meaning and significance as they tend to be depicted through the ‘Hindu gaze of privilege.’

Extending this argument in terms of the intersection of both faith and gender, one can perhaps argue that Sikh women are faced with the double burden of both the male gaze as well as what Mehta terms the ‘Hindu gaze.’

Sikh women in Bollywood

With Sikh women not possessing as apparent an identifier as their male counterparts, who usually don turbans, we often see the experience of Sikh women confused with that of Hindu women. This is seen through visible holes in plots that fail to even respect the basics of the religion. For instance, in the film Hum Tum (2004), when Rani Mukherjee’s supposedly Sikh character is offered a cigarette by Saif Ali Khan, she goes ahead and tries it. However, it is common knowledge that practicing Sikhs do not smoke, yet this fact is disregarded in the film. Not just this, it seems as though the stereotypes that cloud the faith, such as one that views Sikhs as either aggressive or comic elements, are seen to stretch across to the women of the faith as well.

Either depicted as chirpy, bubbly girls like Geet in Jab We Met (2007), Veera in Dil Bole Hadippa (2009), and Mini in Tere Naal Love Ho Gaya (2012), mostly with shorn hair, or as aggressive, bold women like Balbir Kaur in Chak De India (2007). What is essentially lost is the experience of the ‘normal,’ Sikh woman, one who is not trying to fight or have a happy-go-lucky personality.

In Jab We Met (2007), a film that garnered massive praise and a cult following, we see Geet, a chirpy, bubbly Sikh girl who oscillates between her aggressive and playful behaviour. In a particular scene, she is even seen threatening people by priding herself on her identity as a ‘Sikhni.’ Films like Dil Bole Haddipa (2009) and Tere Naal Love Ho Gaya (2012) also depict women as carefree and no-nonsense, often serving as lighter and comic elements of the film.

In Chak De! India (2007), the Sikh character, Balbir Kaur, is seen displaying aggression from the beginning of the film and continues to do so until she is ‘trained,’ by the coach. In other films like Singh Is Kinng (2007), while the faith of Akshay Kumar, who essays a Sikh man, is glorified and celebrated, there is hardly any emphasis on Katrina Kaif’s faith in the film, who also appears to be hailing from a similar background. Despite being marketed as a film that celebrates the Sikh religion, the film only touches upon the men who practice it and arguably neglects the females of the faith, as is so apparent by the title.

What also is lost on screen is the representation of the baptised Sikh women, or Amritdhari women, who have noticeably never seen themselves on screen. Perhaps because of the lack of a ‘glamour,’ element or concerns, they may not grab the eyeballs of the masses.

Sikhs as comic elements

As Anjali Gera Roy argues in her chapter in the book Sikh Formations, Sikhs are either depicted as ‘brave warriors,’ or ‘uncouth rustics.’ Often, to add a hint of ‘humour,’ in the film, one can spot Sikh characters squeezed in the margins. The argument also stretches to films like Son of Sardar (2012) in which Ajay Devgn and Sanjay Dutt essay the role of Sikhs who are reminded of the greatness of their faith only by the end after cracking senseless jokes for the entire duration of the film. From the little child counting stars for the entire duration of Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998) to Anupam Kher’s character in Mohabbatein (2000), who speaks of himself in the third person and dons a polka dot patka and dungarees. If one needs an introduction to the usage of Sikhs as humorous elements, then a close look at Johnny Lever’s filmography should be an apt introduction.

For instance, in the film Raja Hindustani (1996), Johnny Lever, who plays a Sikh, embodies every stereotype in the book that the community is associated with. From the style of the turban to his doing Bhangra with Aamir Khan’s character while uttering the most random things associated with Punjab, we see an ignorant and careless portrayal of the community. What saddens one more is that this is not the first and last time that Lever has done so. In the film Badal (2000), Lever and Upsana Singh’s portrayal as a Sikh couple can serve as a guide on how NOT to use Sikh characters as comic additions in the film. From the dialogue to the attire to the accent, the film goes all the way to make an exceedingly exaggerated portrayal of even the stereotypes and appears to be heavily detached from reality. From Arshad Warsi’s Ghanta Singh in Double Dhamaal (2011) to Vir Das and Boman Irani’s Santa Banta Pvt Ltd (2016), Bollywood does it time and again.

Even recently, in the film Good Newwz (2019), which was overall meant to be a comedy. We see Diljit Dosanjh’s character as the ‘unsophisticated,’ man who always cracks jokes and one-liners and is frowned upon by the seemingly posh and ‘sophisticated,’ couple essayed by Akshay Kumar and Kareena Kapoor.

Women of faith in Punjabi cinema

The role and portrayal of women in Punjabi cinema have evolved over the years. It is not uncommon to spot female Sikh characters in Punjabi films. As Dr Harneet Kaur notes in her paper, “Contemporising Punjabi Cinema: Chronology and Culture,” the role of women in Punjabi cinema oscillates between diametrically opposite roles: the mother or the caregiver and the lover.

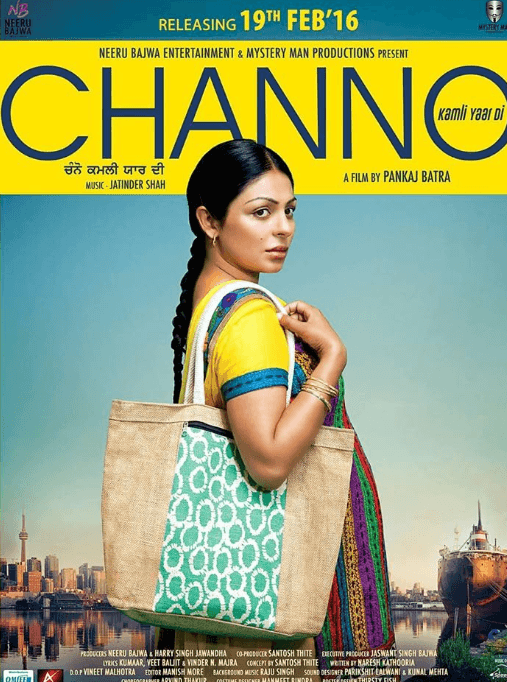

Dr Kaur, in her paper, further notes how women in Punjabi cinema are idealised versions seen through the man’s eyes, deeply embedded in patriarchal norms, with heroines often being ‘light-skinned with long hair,’ and the matron/mother being ‘plump and usually a nag.’ It is amid these characteristics that one sees the development of Punjabi women. However, in recent years, a lot has changed in Punjabi cinema. The arguable rise and popularity of female Punjabi superstars like Sonam Bajwa, Neeru Bajwa, Nimrit Khaira, and Sargun Mehta, among others, has created a buzz where we no longer see women as mere accessories complementing the men but as strong, independent figures on their own. The past few years have seen some women-centric stories like Channo (2016), Gelo (2016), Daana Paani (2018), Needhi Singh (2017), Gudiyaan Patole (2019), and Ardab Mutiyaraan (2019). The last few films featuring women as central characters challenged the dogmas.

With more and more Punjabi actresses like Sargun Mehta, Neeru Bajwa, and Mandy Takhar turning producers, one can only hope that narratives scripted by women for women will enter the industry & help change its status quo.

As Kaur notes, films these days are incomplete without the presence of actresses like Nirmal Rishi, Anita Devgan, Prabhsharan Kaur, Neeta Mohindra, Jaswant Daman, and Rupinder Rupi. Playing the role of matriarchs, their presence does little or nothing for the plot; however, their portrayals do highlight, as Kaur notes, Punjabi culture, food, attire, and mannerisms. However, Punjabi cinema, as one that reflects the realities of the culture and society, has to go a long way in establishing a strong feminist discourse, yet provides plenty for Bollywood to learn from. With more and more Punjabi actresses like Sargun Mehta, Neeru Bajwa, and Mandy Takhar turning producers, one can only hope that narratives scripted by women for women will enter the industry & help change its status quo.

It is also important to understand that in the day and age where we are looking to expand our horizons to newer identities and more integrated societies. Where we perhaps should be looking towards representation for alternate genders and sexualities of the faith, we lie at a standstill point where we can barely manage any form of representation for the faith, let alone the marginalised genders.

The reductionist approach that reduces and twists the realms of people’s identities to more palatable, glamorous ways distorts the representation of real people. Such a representation creates a great deal of alienation between a person holding those identities and the art form itself. While Sikh men may be getting roles in Bollywood, a script that features them as protagonists is still far from the norm established by the industry. While we still see Sikh men in supporting roles, one can safely conclude that the arrival of the women of the faith in the mainstream is yet to take its course. Till then, the regional films have little but enough to begin with.

Part of the title for this article is borrowed from Anjali Gera Roy’s work.

This is not random, it’s a very intentional portrayal of the marginalised community burdened with the conservation of a Civilization with its unique spiritual and social identity as it erodes and transforms into western Anglican and Christian belief systems.