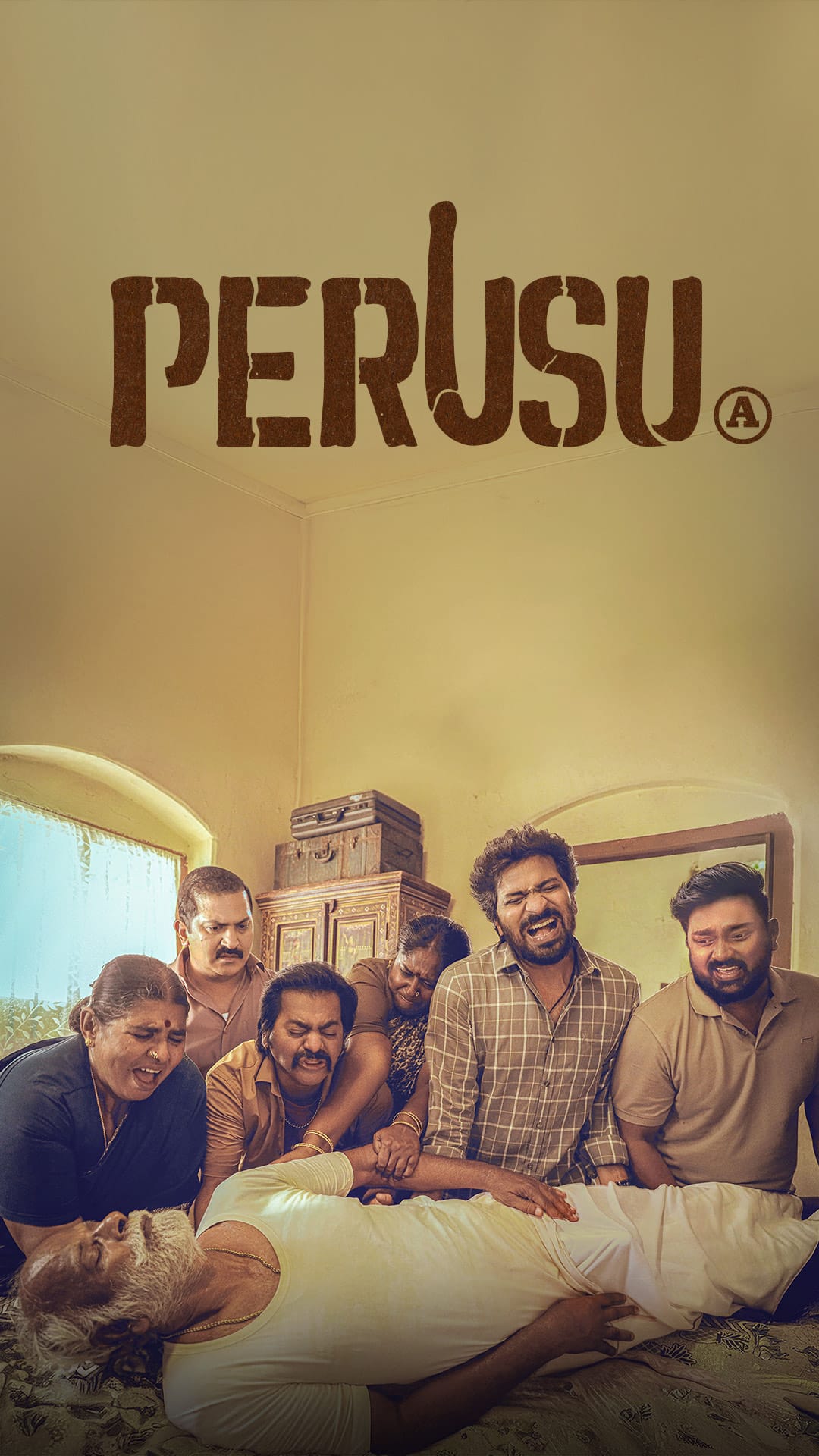

Perusu is a 2025 Tamil-language black comedy film directed by Ilango Ram. With this film, he makes his Tamil directorial debut, adapting his own 2023 Sinhalese-language film Tentigo. The film features an ensemble cast including Vaibhav, Sunil Reddy, Niharika NM, Chandini Tamilarasan, Bala Saravanan, and others. Having been released on March 14, 2025, Perusu was marketed as an “adult comedy” with quirky characters and outrageous circumstances.

But underneath its comedic veneer lies a scathing commentary on how shame, honor, and masculinity intersect in deeply gendered and repressive ways within Indian families and village life. The plot kicks off with the death of Halasyam, an aging patriarch in a Tamil Nadu village, who dies unexpectedly (and rather inconveniently for his family), with a sustained penile erection. This single physical detail sets off a cascade of panic, fear, and increasingly bizarre measures as his family desperately tries to prevent the villagers from finding out. What ensues is not just slapstick absurdity, but a reflection of how patriarchal norms have conditioned people to view natural human desires, especially when associated with the elderly, as vulgar or shameful.

Perusu, though pegged as a comedy, dives into heavier themes: the fear of ostracisation, the social policing of sexual expression, especially among the elderly, and how a community’s fixation on “respectability” can completely suppress human vulnerability. The film plays out in a village setting, which is key — the tight-knit social structure and performative morality of such communities amplify the family’s anxiety. Yet, while humorous, the film also mirrors uncomfortable truths.

The fear of losing social standing overrides even basic human emotions like grief, love, and acceptance. But Perusu is also layered with contradictions and moral paradoxes, some of which it resolves in laughable ways, and others it leaves disturbingly open. It holds a mirror to how deeply embedded societal taboos (particularly those around sex, death, and masculinity) dictate behavior across generations, often turning private sorrow into public performance.

Domination of societal fear and shame in Perusu

The central plot of Perusu revolves around Halasyam’s family, his two sons, Duraikannu and Samikannu, their respective wives, their mother, and their aunt. Upon discovering how Halasyam died, the family becomes consumed by the fear of societal judgment. The visible erection is not inherently problematic; after all, the male characters in the film frequently engage in jokes about past romantic escapades and sexual innuendos. The issue arises because it is Halasyam, affectionately referred to as “Perusu” (a colloquial term for an old man in the village), who died in this state.

In the village’s patriarchal framework, elderly men are expected to embody wisdom and respectability. Open expressions of sexual desire, especially at an advanced age, are deemed inappropriate and shameful. This is particularly true when such desires cannot fulfill the patriarchal objective of procreation within a marital relationship. The family’s overwhelming fear of societal embarrassment leads them to take extreme measures, consulting doctors, veterinarians, and even shamans, to conceal the truth.

This pervasive fear inhibits the family’s ability to grieve sincerely. Their immediate reactions are not of sorrow but of second-hand shame and anxiety over potential embarrassment. They avoid seeking support from relatives or neighbors, highlighting how deeply the fear of societal judgment can suppress natural human emotions and responses.

How ostracism drives dehumanisation

In their desperate attempts to “eliminate” the perceived problem, the family embarks on a series of absurd endeavors, including trips to hospitals and even a butcher’s shop. They fabricate elaborate lies to tell neighbors and well-wishers, often bordering on the ridiculous, all to ensure that the truth remains hidden. In doing so, they vividly reinvent Halasyam’s life story, exaggerating his career achievements and last wishes, effectively erasing his individuality and humanity.

In doing so, they vividly reinvent Halasyam’s life story, exaggerating his career achievements and last wishes, effectively erasing his individuality and humanity.

The time that should be reserved for mourning becomes a period of orchestrated deception in Perusu. Halasyam’s state of death becomes the subject of crude jokes and double entendres, further dehumanising him. Ironically, while the family is adamant about keeping the truth from the public, they have no qualms about making jestful remarks among themselves.

Moreover, the family’s focus shifts rapidly from grief to concerns about property inheritance, a mere day after Halasyam’s death. This underscores how patriarchal structures prioritise material and social standings over genuine emotional connections, further devaluing the individual’s life and desires.

Gendered glorification of patriarchal immorality in Perusu

As the plot of Perusu unfolds, revelations about Halasyam’s extramarital affairs with a sex worker come to light during the funeral proceedings. There are also subtle hints that he possessed erection-stimulating pills. Despite these morally questionable revelations, the family’s primary concern remains the potential embarrassment caused by his posthumous erection. Once the “problem” is resolved (ironically through a physical altercation that deflates the erection) the family breathes a collective sigh of relief. They even go so far as to accept the sex worker as a fellow mourner, acknowledging her relationship with Halasyam.

What is particularly troubling is not just the normalisation of an elderly man’s extramarital affair but the way his life is retrospectively glorified. Perusu opens with Halasyam chastising a young man for leering at women bathing by the riverside. However, it is later revealed that Halasyam himself was the voyeur, exposing his hypocrisy and challenging the village’s perception of him as a “respectable man.”

Despite these revelations, the family expresses admiration for Halasyam’s life. His son remarks, ‘Vaazhntha unna maathri vaazhanum, setha unna maathri saavanum‘ (To properly live a life, one must both live and die the way you did). This statement encapsulates the film’s central paradox: while the family initially fears social shame due to Halasyam’s erection, they ultimately find solace in the fact that it resulted from a relationship with his “keep,” a scenario normalised for older men in the village.

This statement encapsulates the film’s central paradox: while the family initially fears social shame due to Halasyam’s erection, they ultimately find solace in the fact that it resulted from a relationship with his “keep,” a scenario normalised for older men in the village.

This narrative arc highlights the gendered double standards in moral judgments. While male sexual desires, even when expressed immorally, are often excused or even celebrated, similar behaviors in women are stigmatised. Perusu thus critiques the patriarchal structures that dictate societal norms and the selective morality that often accompanies them.

Perusu is more than just a comedy of errors; it is a social satire cloaked in absurdity. It shows how families are often complicit in upholding patriarchal and moralistic codes, even when these codes erode their own emotional integrity. What makes this journey even more ironic is that, in their desperation to uphold a notion of ‘honor,’ the family ends up enacting rituals and deceptions that are far more immoral or dishonest than the event they are trying to hide. And despite Halasyam being revealed as a man who engaged in voyeurism and possibly extramarital affairs, he is still glorified because his actions conform to a normalised male privilege in patriarchal culture.

Perusu ends not with a resolution of ethical dilemmas, but with a collective exhale, a relief not rooted in truth or justice, but in successfully navigating shame. That, perhaps, is its most accurate reflection of society. It might draw laughter from audiences, but it also leaves behind a sense of discomfort , the kind that lingers when we recognise that what we’ve been laughing at is painfully real. It reminds us that comedy can be a potent tool for truth-telling, especially when it reveals how fear, masculinity, and morality intersect to regulate even death.

About the author(s)

Lakshmi Yazhini is a post graduate student, pursuing an Integrated Masters in Development Studies, at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras. Based in Chennai, Yazhini has an avid research interest in the intersectionality of feminist geography and the state, in peripheral cities. In her free time, she likes to bake, do yoga, read fiction and pen down her thoughts in her journal (which are most often about the micro inequalities around her). Yazhini hopes to explore, write and make a difference about these as a policymaker some day.