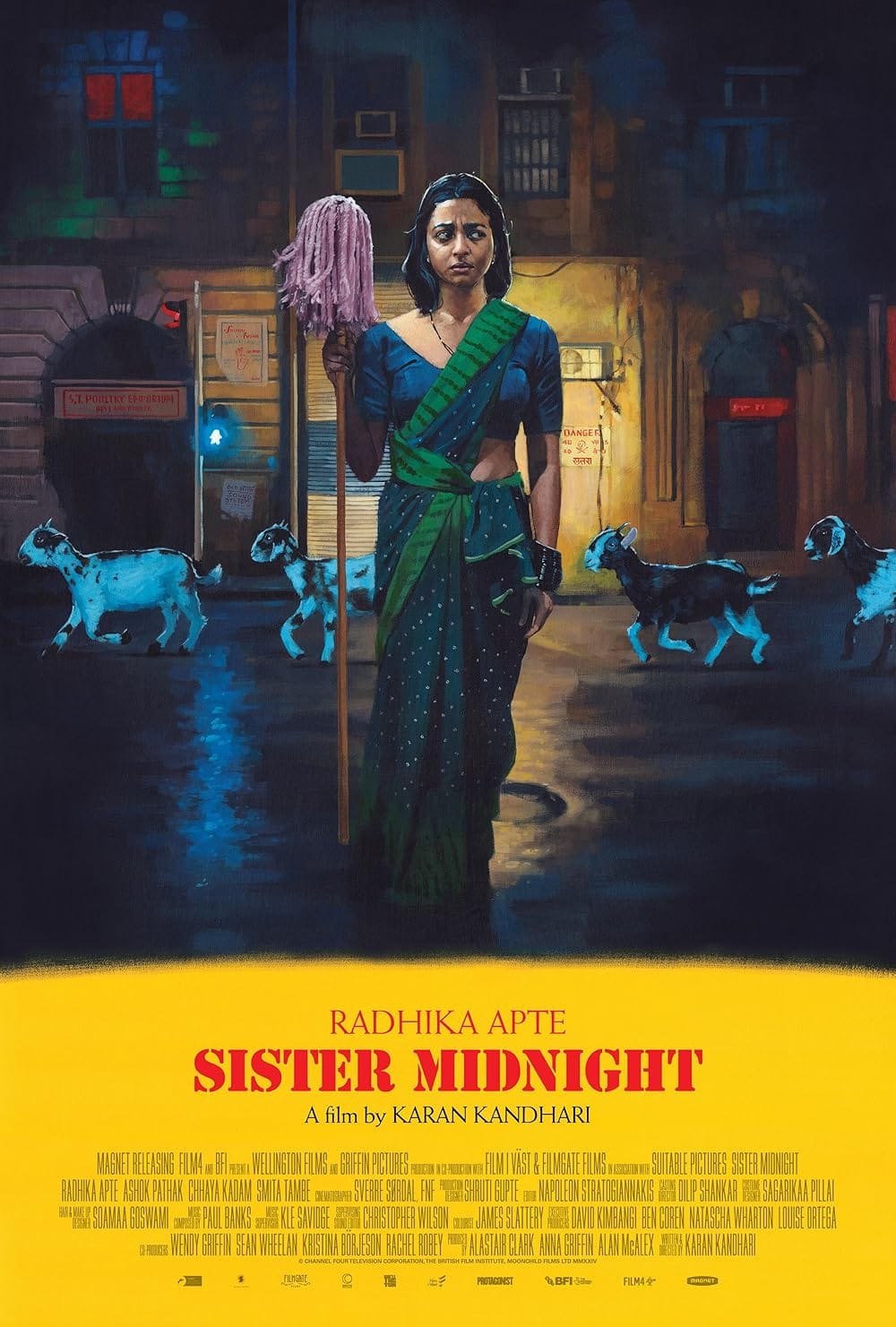

In the stifling corridors of Mumbai’s lower-middle-class chawls, where ceiling fans churn the weight of women’s expectations and tradition passes hands like unpaid bills, Sister Midnight unfolds—not as a celebration of romance, but as a dissection of domestic incarceration. Karan Kandhari’s debut feature is a furious, genre-defying howl against the machinery of patriarchy. And Uma (Radhika Apte), our trembling yet tenacious protagonist, is its wounded prophet, its incendiary center.

Uma’s descent in Sister Midnight is not a dramatic fall from grace but a slow, cellular rebellion. Apte imbues her with a kind of quiet, lived-in ache that accumulates across the film like damp in the walls. From the moment she steps into her husband’s home, her very body flinches—as though entering a well-appointed cell. She is not welcomed but absorbed, processed into domestic servitude, folded into ritual, drained of identity.

Gopal, her husband, is no brute in the conventional sense. He is the quiet face of patriarchy—polite, clueless, and devastatingly indifferent. He does not hit. He dismisses. He offers handshakes in place of intimacy. He drinks instead of engaging. His indifference is the perfect weapon: sharp enough to wound, invisible enough to forgive—a violence that Kandhari wields like a scalpel, exposing it not through spectacle but with surgical estrangement.

Uma: the initiator of a sèance

Apte makes Uma’s resistance in Sister Midnight visceral. Her silence is not submission but sharpening steel; her outbursts are not chaos but language. She slams doors, stares with contempt, refuses to perform the exhausting rituals of femininity. Her hallucinations—a mosquito bite that spirals into terror, birds pecking at her skin, a goat that stalks her with prophetic silence—are not symptoms of madness but metaphors of psychic protest. They are eruptions of a body that has run out of words, of a mind that has been too long ignored. Her breakdown is not a crack but a statement. Her defiance builds slowly, fed by years of accumulated dismissal, until it bursts through the seams of ritual and role.

Radhika Apte, in one of her most unsettling performances, transforms the quietly dying woman into a vessel of accumulated chaos. Her Uma is not staged to inspire pity or reverence but discomfort—a character designed to disrupt, not reassure. In Apte’s body, the character’s physical unease becomes language. Her shoulders, stiff with invisible weight; her eyes, scanning the periphery for exits that don’t exist; her voice, clipped and curling at the edges—all of it contributes to a character that is not merely suffering but testifying.

Her portrayal in Sister Midnight veers deliberately away from sanitised portrayals of female pain. Instead, she imbues Uma with the dissonance of being constantly misread, mislabeled, misunderstood. The violence Apte embodies is not performative. It is bone-deep, nearly invisible until it ruptures the wallpaper of domesticity. Hers is not the rage that seeks justice—it is the rage that seeks air.

When she begins to push back—refusing tasks, wielding silence like a weapon, unleashing her voice—it is not chaos. It is clarity.

When she begins to push back—refusing tasks, wielding silence like a weapon, unleashing her voice—it is not chaos. It is clarity. And she chooses instead to rot, to rage, to refuse.

Kandhari’s depiction of resistance on screen in Sister Midnight

What is remarkable in Sister Midnight is not just Uma’s descent into psychosis but how Kandhari films it. The film uses surrealism not as ornament but as indictment—each of Uma’s hallucinations pulses with symbolic fury. They reflect how Kandhari understands madness: not as deviation but as consequence, a mirror to cruelty.

Kandhari frames this fury with unflinching honesty. His visual language refuses to aestheticise suffering. The chawl is rendered not as spectacle but as trap—narrow corridors, dim bulbs, the architecture of claustrophobia. Every wall presses in. The house is not a haven but a pressure chamber. Kandhari uses surrealism not as flourish but as indictment—every vision Uma experiences is loaded with meaning. The pecking birds, the blistering sun, the haunting goat—each surreal image pulses with political charge. Madness, in Kandhari’s gaze, is not pathology. It is consequence.

His critique is clear: women who refuse to disappear are branded hysterical. The hallucinatory sequences are Kandhari’s way of visualising what can’t be said aloud. When language fails, the subconscious takes over. And in Kandhari’s hands, the subconscious is not dreamy—it is damning. It indicts every gesture of polite patriarchy, every smile that masks condescension, every ritual that demands women fold themselves smaller.

Yet Kandhari doesn’t build Uma as a martyr. He allows her to be absurd, comic, contradictory. The film laces her rebellion with grime and humour. When she lets a pet dog escape, when she lies to get a job, when she decorates her husband’s decomposing corpse with marigolds and fairy lights—these are not signs of madness but rituals of reclamation. Each act is a small, grotesque revolt. Her resistance in Sister Midnight is not cinematic heroism—it is survival by sabotage. And when Gopal dies—accidentally, erotically, almost tenderly—it is not revenge. It is culmination. A domestic climax, soft and rotting.

The surrounding characters sharpen Uma’s defiance by contrast. Sheetal (Chhaya Kadam), her bawdy and battle-worn neighbor, is both comic relief and grim caution. Her words, ‘Romance, adventure? This is a garbage dump. Pick your pile,‘ cut with the precision of lived truth. She survives not by breaking the rules but by laughing at them. Her sarcasm is not liberation—it is armour.

Through Sheetal, we see what compromise looks like after decades: not strength but exhaustion.

Through Sheetal, we see what compromise looks like after decades: not strength but exhaustion. Where Sheetal adapts, Uma breaks. Sister Midnight does not condemn either—it contextualises them. It lets us see the cost of both endurance and refusal.

The myth, the madness and the woman

The final act is where Kandhari’s allegorical impulse burns brightest. After cremating her husband with the help of a band of transgender allies, Uma finds momentary refuge in a Buddhist monastery. The monastery offers no divine comfort—only the dignity of silence. These women, cloaked in simplicity, have rejected domesticity not in rage but in refusal. Yet even this sanctuary cannot save Uma from society’s verdict. When her home is torched and birds fly out of the flames, Kandhari hands us his closing metaphor: a woman who dared not to disappear must be turned into a myth.

She is no longer a wife, widow, or madwoman. She is a spectre. A danger. A legend that haunts patriarchy’s conscience.

And yet, what Radhika Apte conjures with Uma is not a myth. It is a method. The flick of black lipstick. The refusal to run. The final dare in her eyes as she faces a mob with no weapons but her body and her silence—these are not the gestures of madness, but of a mind sharpened by survival. Her performance is clenched, unsanitised, defiant. She is not the martyr or the muse. She is not palatable.

Sister Midnight doesn’t grant Uma salvation. It grants her visibility. And that, in a world engineered to erase women, is its most radical gesture. To be seen. To rot loudly. To refuse the seduction of politeness. Sister Midnight is not just a film. It is a requiem—a shriek beneath fluorescent kitchen lights, a dirge for every woman told her anger was unseemly, her pain excessive, her body disposable.

It rejects redemption arcs and sanitised resilience. This is a love letter to the unloved, a hymn for those whose hands have bled from cleaning up the emotional debris of men too fragile to face their own power. A war cry disguised as domesticity—a slow-burning revolt stitched into spilled lentils, chipped bangles, and lipstick smeared defiantly beyond the lines.

Through Kandhari’s searing lens, Sister Midnight honours that resistance not with healing, but with fury.

Through Kandhari’s searing lens, Sister Midnight honours that resistance not with healing, but with fury. With a woman who walks into the fire of her undoing and calls it liberation. Not pretty. Not poetic. Just free. And in a world addicted to obedient ghosts, that freedom is terrifying, yet it is the only candor.

Do we often mistake defiant silence for madness in female characters? I think so. I’ve seen strong women labeled “difficult” simply for refusing to conform. It’s easier to dismiss them than to acknowledge their strength. I wonder if Apte’s Uma would enjoy a game of Pacman 30th Anniversary.