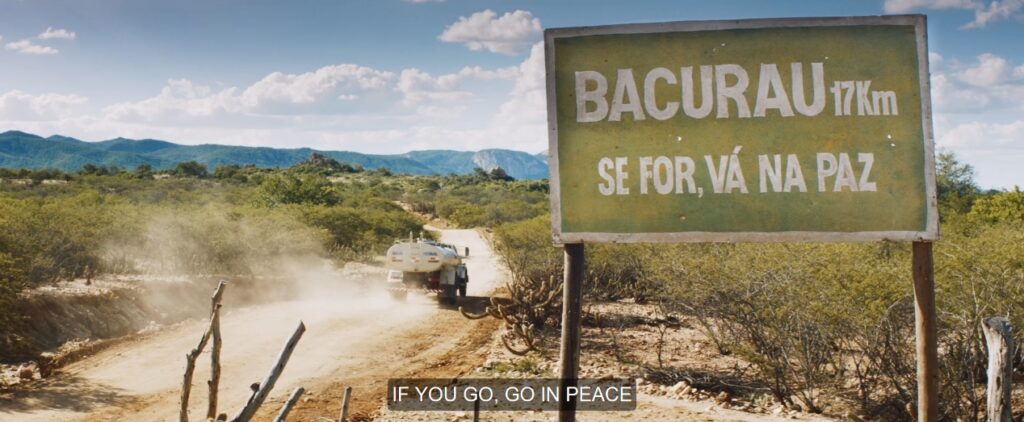

Bacurau (2019) directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles falls under the genre of weird western. The film is set in Bacurau, a small fictional settlement, in Pernambuco, a state located in the North-East region of Brazil. The story is set in the future and revolves around how the inhabitants of the region are endangered by foreigners who invade the village and kill the inhabitants for ‘fun’. The village also suffers a water scarcity as a result of their water source being cut off by the State, and their access to the main city Serra Verde is also obstructed, putting a timer on their already limited basic supplies. As a result, they have a troubled relationship with their mayor who only visits the village during the time of elections. The film revolves around how the community tries to survive with these challenges being whirled at them.

Also read: Eeb Allay Ooo! | Film Review: A Political Satire On The Isolation Of The Marginalised

Bacurau (2019) directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles falls under the genre of weird western. Bacurau is a small fictional settlement, in Pernambuco, a state located in the North-East region of Brazil. The story is set in the future and revolves around how the inhabitants of the region are endangered by foreigners who invade the village and kill the inhabitants for ‘fun’

The importance of the genre of Bacurau- Weird western, is to emphasize the physical setting itself and its relevance to the film and the topic of the essay. The Western genre specifically works around and stresses the harshness of the wilderness, the vast, dry, desert lands. In addition to this, the weird western genre also carries elements of horror, occult, and fantasy which are observed in the film through the cultural practices of the residents. The reason for getting into this technicality is to draw a correlation to the directors’ requirement for such a setting and also the popular association of desert regions and thick dry vegetation to the presence of ‘criminal’ tribes.

In the Indian context, we associate or used to associate these locations with the lurking of the Dakoo (a.k.a.) Dacoits. In movies like Sholay (1975), we notice Gabbar Singh hanging around with his gang in the rocky terrain somewhere in Karnataka. The location was inaccessible to the extent that the producers of the film had to construct a road to reach there for shooting the film. Historically, colonial representations of thuggees—’criminal tribes’ were often in such inaccessible regions and the landscape also provided camouflage for these groups and due to their vastness, were easy to run away and hide into. We notice the depiction of a similar region in the short film Bypass (2003) in which Nawazuddin Siddiqui along with his accomplice hide behind boulders to jump passers-by and loot them.

Bacurau, opens with Teresa, a resident returning home to attend her grandmother’s funeral. She is wearing a lab coat and is asked by a fellow villager why she is wearing it, to which she responds- “Let’s say it’s a kind of protection”, which can be an extrapolation to the restrictions on accessing professional spaces, in which Teressa a non-white individual has found access to. The lab coat is then a symbol of her claiming the space and standing up to white oppressions on non-white individuals.

The main plot of the film revolves around a bunch of American’s who visit Bacurau with an aim to kill the residents. The killing is a game and each kill is tracked and scored to predict the winner. The game could also be extrapolated to the colonial fascination behind hunting and their viewing of the natives as ‘savage’ and ‘animalistic’ and hence worthy to kill. The audience is taken through the entire orchestration which begins with the shutting down of network signals to Bacurau and removing them off the map to ensure there is no way of tracking them or even proving such a place existed. During the planning of the attack, the town is studied by unknown flying objects which is a drone to surveil the area and track the movement of the residents to plan a kill. A similar technology is also seen at work in defence/military forces where surveillance is used to locate the enemy and take them out. It is ironic that technology justified as protecting individuals is used by the State and stakeholders for invading one’s privacy.

Things escalate and the residents of Bacurau find themselves in the middle of a real-life game. The residents get enraged as a child is murdered as part of the game. They gather all the weapons and arms they can find in order to fight back and save their town. Here the concept of violence enters a grey area in which some individuals use it as a game for fun versus for others it is a survival mechanism and the only way of fighting back. The Americans later also justify the killing of these residents by portraying them as ‘threats’. The choice of weapons further establish how certain forms of violence are legitimized while others criminalized. The gun used by the Americans, also a weapon used by security forces to control and use against natives who are unpredictable with their dangerous tools a machete, a spear. Due to the film being set in the future, we notice that most residents of Bacurau have access to guns, while some still use handmade tools.

Also read: Film Review: Shiva Baby Effectively Depicts Anxiety-inducing Claustrophobia

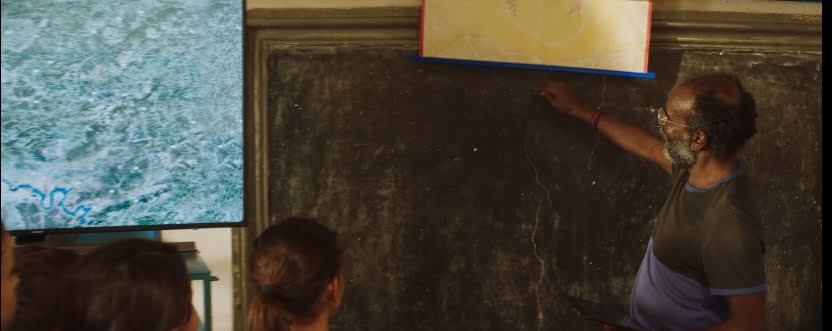

Throughout, we also notice an emotional association the people of Bacurau have with their land and their struggle to protect it. The town has a library, a museum, and a school run by the villagers who pass on their histories to the children. The museum is a particularly interesting space since it is set up by the natives themselves and is not the usual colonial exhibition of conquered collections taken both spatially and temporally out of contexts. Another instance of importance to land is brought out in the scene where Plinio, the librarian and teacher is trying to locate Bacurau on the map to show the children and is surprised when he is not able to find it (remember signals were cut off). The audience can notice the anxiousness and fear creep in his face as he realizes there is nothing to legitimize their existence. The idea of land being marked and demarcated by boundaries on a map is so inherent to the identities of the inhabitants and also in this case seems to have provided them certain security which was lost when there was no proof of their existence, making it easier for the Americans to kill the inhabitants and not be held accountable for.

The film also brings out the troubled relationship between the people of Bacurau and the State. We become aware of this by the villagers’ unhappiness with the mayor and their unsaid but obvious desire to completely disassociate from the state. Later, we also realize the mayor had a role to play in the Americans entering the village and causing havoc for monetary exchange which can be juxtaposed to the contemporary context of how corporates join hands with politicians and political parties to take over communities and their lands. Lunga, one of the characters in the film who we are introduced to as a resident of Bacurau, is in hiding since the State is on the lookout for his capture. He is presented as a character who is criminalized for standing up against the state to protect his community. Similarly, colonized India too observed the misuse of laws by the British regime to keep specific community groups in check by categorizing them under ‘criminal tribes’ and enforcing an Act that criminalized several of the marginalized communities. Several lower caste communities and members of transgender groups were put into the category for scrutiny and incarceration. Many believed this to be an outcome of racial as well as a cultural hierarchy within the country itself. Crimes thus became associated with caste groups further pushing certain communities out of societal bounds to be oppressed and ostracized by better-to-do castes.

The film has a rather interesting take on the notions of crime and violence by subverting the popular media association of crime with members belonging to certain cultures and portraying the State as saviours and upholders of the law. The western genre also used its plots and themes to glorify violence against a community by otherizing them and in the process typecasting them as an enemy- for example: a white cowboy fighting a Native American over land and portraying him as the hero. Bacurau stands out since it does not shy away from portraying violence and struggle. It also does not place any character as a victim to be ‘saved’ which is often a stereotype associated with indigenous communities. The portrayal of certain stereotypes and associations made about tribal or indigenous communities such as the geographic hideout, indigenous weapons, fashion and the cultural practices, almost seems to be the directors mocking the audiences’ and larger publics’ naivety in the depiction and interpretation of closed, peaceful communities as mysterious, violent to be interfered with and corrected.

The portrayal of certain stereotypes and associations made about tribal or indigenous communities such as the geographic hideout, indigenous weapons, fashion and the cultural practices, almost seems to be the directors mocking the audiences’ and larger publics’ naivety in the depiction and interpretation of closed, peaceful communities as mysterious, violent to be interfered with and corrected.

References

Singha, Radhika. ‘Providential’ Circumstances: The Thuggee Campaign of the 1830s and Legal Innovation.” Modern Asian Studies 27.1 (1993): 83-146.

Cole, Simon A. Suspect identities: A history of fingerprinting and criminal identification. Harvard University Press, 2009.

Arundhati Narayan is currently pursuing her Postgraduate degree in Women’s Studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Her current research interest includes understanding the changing discourses on witchcraft in academia and society. In her free time, she also enjoys gardening, experimenting with recipes while listening to a wide genre of music. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram.

Featured image source: The Guardian

All inserted images are screengrabs provided by the author.