Cooking occupies an increasingly vexed space in feminist discourse, often stirring up passionate debates about choice, identity, and empowerment. On one hand, cooking is seen as an act of nurturing and creativity, a way to connect with loved ones and culture. On the other hand, it raises questions about traditional gender roles and the pressures women face to fulfil domestic expectations. As we navigate this complex landscape, it becomes essential to explore how cooking intersects with feminism, revealing both the joys and challenges of reclaiming the kitchen as a site of agency and expression.

The constant tug-of-war between being a socially compliant cook and a feminist plagued my mind as a young girl. My relationship with cooking started rocky, and I resisted it for a long time. However, I eventually discovered the joy of preparing meals and sharing them with my loved ones. This story is my mixed bag of ingredients with cooking and trying to reclaim the dinner table while shedding the guilt of not being “feminist enough.”

As a child of a working mother, I was often teased by relatives– “Your mother doesn’t know how to cook.” One day when it all felt too much, I ran to my mother, who had just finished her hospital shift, and asked for besan ka halwa. She had that knowing gleam in her eyes when she brought a piping hot bowl of golden goodness to me. I ran around the house, parading it and screaming, “My mum can cook!” at anyone who would listen. She said to me something her Amma (grandmother) always preached, “bhale hi zindagi mein kabhi zaroorat na pade, par har insaan ko saare kaam aane chahiye.” (tr. Every person should know all life skills even if you won’t need them ever in your life.)

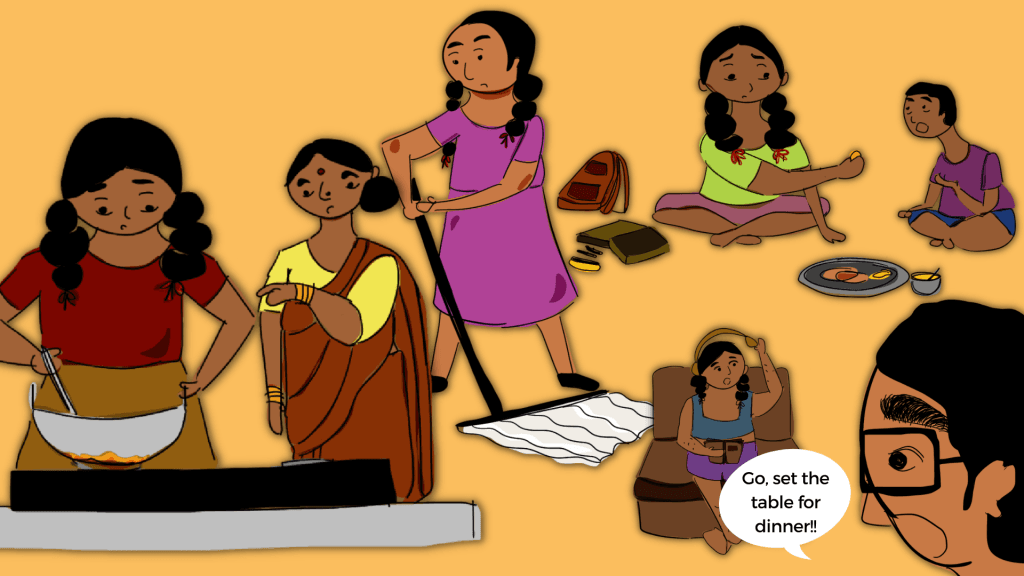

Coming from a quintessential UP-Bihar-rooted family who are ardent devotees of food, devouring 15 kg of meat on the regular, cooking felt like a war won when acknowledged by diners. Until it wasn’t, and you were knee-deep in the swamp of societal expectation, mockery and dual burden.

Women and girls in my family would cook delicacies, garnering appreciation from family and relatives but I, till I became a young adult, could not bring myself to cook anything but Maggi and cheese macaroni, especially not for other people. The thought of stepping into the kitchen to fend for someone other than myself filled me with dread and anxiety. It was during the pandemic that I realised the dilemma. The act of cooking was not the problem, the scrutiny was. Coming from a quintessential UP-Bihar-rooted family who are ardent devotees of food, devouring 15 kg of meat on the regular, cooking felt like a war won when acknowledged by diners. Until it wasn’t, and you were knee-deep in the swamp of societal expectation, mockery and dual burden.

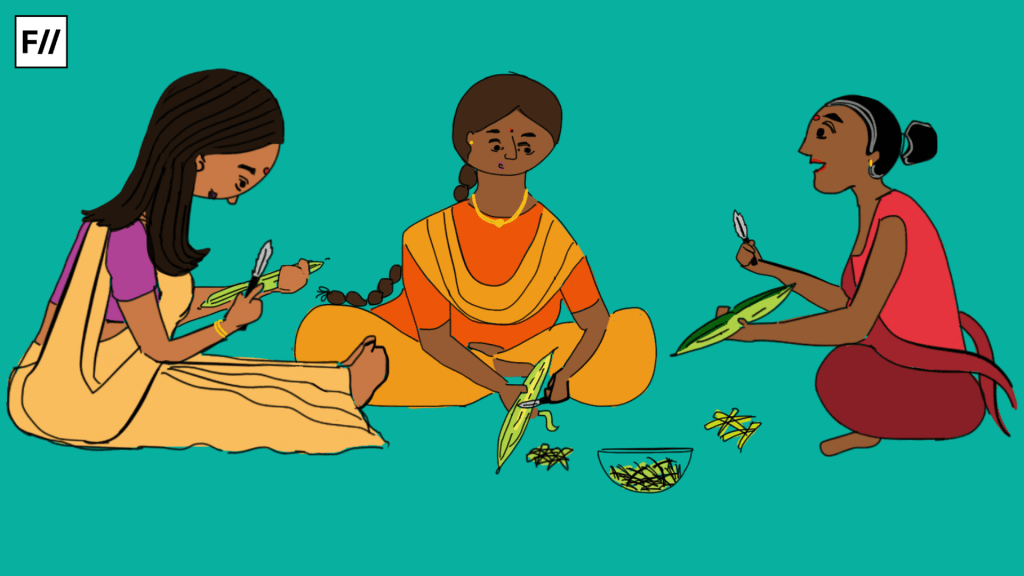

It was only when I was at my Nani’s home during the pandemic that my love for feeding people flourished. The most supportive and unprejudiced people in my life– My Nana, who patiently taught me how to knead the dough until every bit of flour was cleaned from the bowl, and my Nani who, despite her constant worries about our safety and her guilt in watching us work, trusted me with her kitchen. Even when I cooked paneer curry too salty or a shahi tukda too soggy, the only words that came out of my Nana’s mouth were “kya shaandar khana bana hai!” (tr. What a wonderful meal!) and there, it hit me like an epiphany and a harrowing reality.

Cooking was meant to be joyful, and without judgement and not many women were able to feel that way. I became very aware of the privilege I had, of being able to enjoy the act of cooking without the pressure of scarcity or the burden of necessity; truly a luxury not sold in the mandi or on Groffers.

It should have been about taking control of the narrative—choosing what to cook, when to cook, how to prepare it, and who to share it with. Each dish becomes a statement of identity, a way to celebrate heritage, and a space for commensality. Sharing meals to bridge gaps between generations, cultures, and experiences and an opportunity to pass down recipes and stories, empowering the next generation to embrace their roots while inspiring them to make their own culinary choices; something my mother has been doing with me through her repertoire of egg biryani, paneer kulcha and sponge cake recipes.

Fortunately, for me, cooking became a form of self-care and personal expression. The act of preparing food is almost meditative while experimenting with flavours and techniques encourages me to explore my tastes and preferences, not what is prepared and loved by others.

Living with my childhood friend in a city away from home, the kitchen transformed into a sanctuary of collaboration, where laughter and conversation flowed as freely as the ingredients. In those moments, the burdens of daily life felt a little lighter. I found not just camaraderie but also acceptance in the shared experience of cooking—whether crying while chopping onions, experimenting with spices or laughing over shared mistakes. Sitting together for a meal became a powerful act of resistance against the isolation that often pervades urban life. Sharing food amplified trust and intimacy, opening up about our struggles and triumphs for hours, creating a support system that nurtures both the tummy and soul.

Cooking and feeding others has been like a masterclass in respecting preferences and choices—kind of what feminism for me is about. Just as every dish has its unique flavour, everyone has their tastes and needs, and honouring those differences is what makes the kitchen (and life) so deliciously diverse! Feeling a sense of belongingness in the kitchen would have irked me as a child but now, I wouldn’t change a thing about it.