Marvel’s Thunderbolts* (2025), directed by Jake Schreier, is not just another edgy anti-hero team-up but also a creative shift for the MCU. The film introduces characters like Valentina (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), Yelena (Florence Pugh), and Ava (Hannah John-Kamen), each bringing their depth and complexity to the narrative. Over time, many viewers began questioning how Marvel had treated its female characters in the earlier phases. For instance, take Natasha Romanoff, who was introduced not with a compelling backstory or inner life but as an enigmatic figure dressed in tight leather suits, mainly designed for the male gaze. Natasha wasn’t given the same emotional space or agency as her male counterparts.

But Thunderbolts seems to be doing things quite differently. It’s centred around nuanced characters, many of them being women, who are not merely strong but also complex throughout. These are not women who simply fight; they question the system, survive betrayal, and command the narrative. The film doesn’t sideline their femininity but reframes it as a source of layered power.

And in doing so, Thunderbolts might just have redefined what it means to be a hero in the MCU. This particular move—it’s not just inclusion but evolution. It’s not just about representation but about reshaping the story itself.

From objectified to observed: The rise of the female gaze

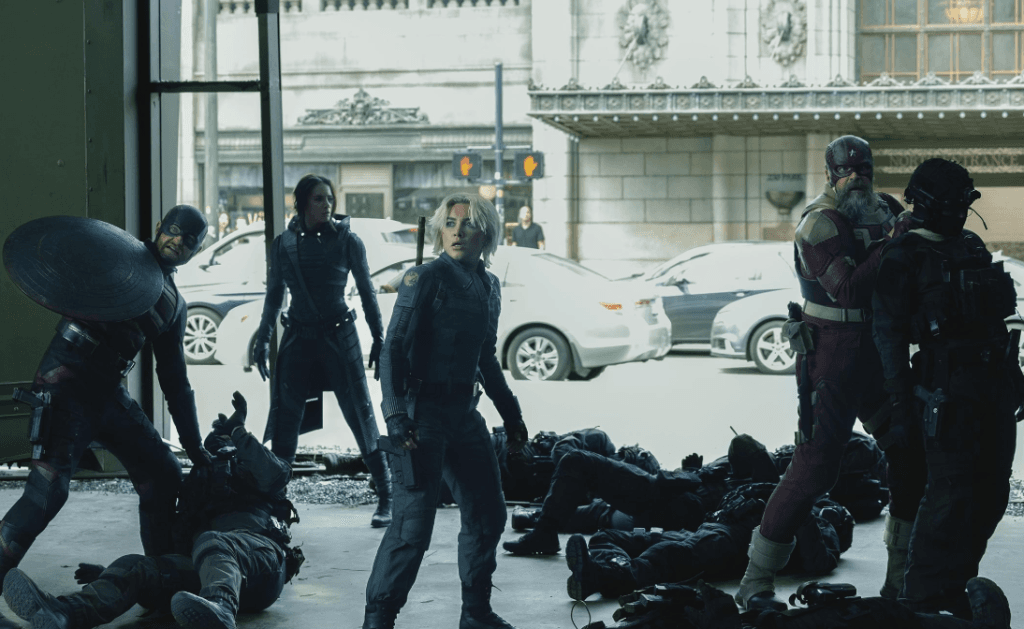

We can see the difference in how Thunderbolts frames its women. In the early phases of the Marvel films, female characters like Natasha Romanoff were often captured via the lens of the male gaze in slow-motion walks, hyper-sexualised suits, and deductive dialogues. But Thunderbolts demonstrates how far Marvel has come in centring women, not just as eye candy but as actual people.

Characters like Yelena and Ava are now shot through a different lens—one that emphasises their emotional depth and resonance, rather than focusing on their physicality. Their bodies are not the focus, but their anger, loyalty, humanity, and pain are too. The female gaze finally takes the lead. And with the female gaze, it doesn’t just reframe what we see; it also reorients how we interpret strength. There is space now for dry humour, awkward silence, and reactions that don’t need explanation. These women don’t serve the story, but they are the story.

The MCU has allowed them to occupy more areas without stripping them of their own agency. The camera doesn’t just look; it’s listening now. And that difference has changed everything.

Women who lead: Valentina and the politics of power

That female leadership can finally stand on its own terms in cinema and the MCU. She is not the stereotypical mentor or the symbol of a moral compass. She is older, strategic, unreadable, and completely in control of her narrative. And that is something worth celebrating. For too long, leadership for women in mainstream franchises has been boxed into traditional tropes—the nurturing mother, the emotional guide, and the redeemable villain. Valentina does not tick those boxes, and more importantly, she does not need to.

In the earlier phases of Marvel, take Maria Hill as an example—she’s a smart and capable character, but mostly shown as Nick Fury’s sidekick rather than a leader in her own right. Her leadership was quiet and at times almost invisible. Thunderbolts, on the other hand, gives Valentina the space to be sharp, ambitious, and unapologetically powerful. The film embraces layered and complex storytelling, and Valentina is the definition of that. She shows us that leadership doesn’t need to be softened or made palatable—it doesn’t have to be linked with likability. It needs presence; it needs command. And for once, Marvel finally lets her have it.

Form meets function: Costumes as commentary

Superhero costumes are not just about fashion; but they are metaphors. And for far too long, women’s uniforms in superhero films have served the male fantasy rather than being functional. That is where Thunderbolt makes a shift. Gone are the days of latex dudes with strategic cutouts. Let’s look at Yelena’s and Ghost’s costumes for a second. To begin with, Yelena’s costume has rough stitching and visible wear, which feels like it has been lived in, and it is not just a form of cosplay. Ghost’s suit is less of a costume but more of an extension of her fractured being that is glitching, glitchy, but never quite whole. This shift is heavily important. They don’t conceal the physicality of the characters, but they enhance it without objectifying them.

Across cinematic memory, women’s costumes in action cinema have been expected to look a certain way and to attend to the male gaze. In Thunderbolts, looking good takes a backseat to looking real. These aren’t just outfits meant to impress, but they are meant to survive. It is very refreshing to see Thunderbolts‘ costume prioritising narrative and not just novelty.

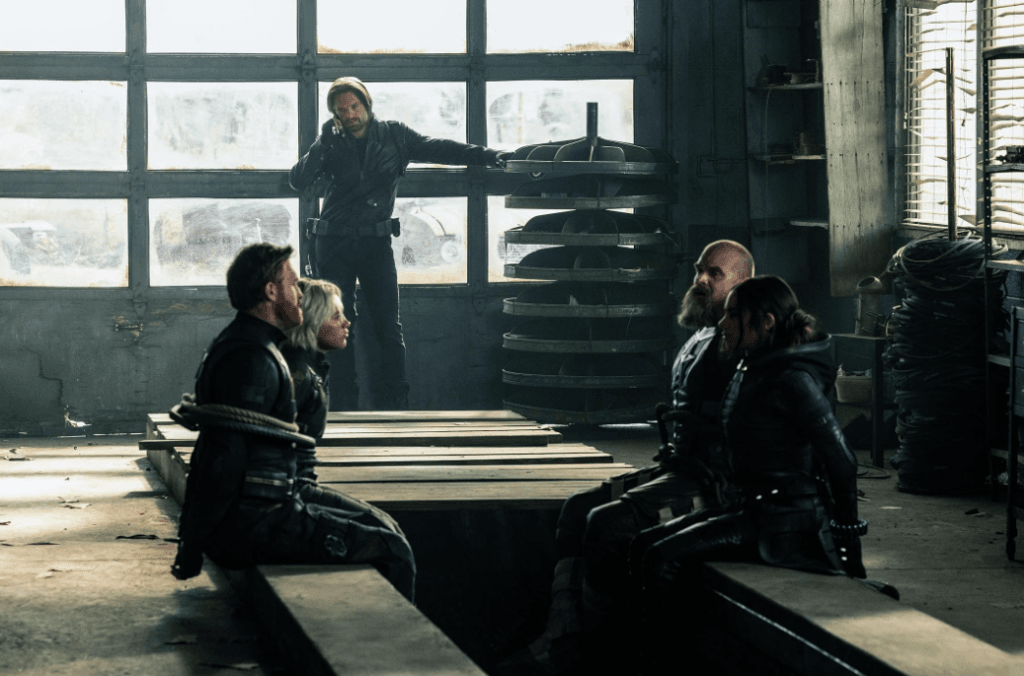

Not just strong, complex: Women with emotional gravity

Thunderbolts does not box its female characters into the same old tropes: the cold killer, the love interest, or the strong female character with no depth. We see a strength in its female characters, one that embraces vulnerability as part of power. Yelena hides her pain behind sarcasm. She often jokes too much because silence reminds her of loss and abandonment. And Ghost, with her constantly phasing body, physically shows what it’s like to be dissociated from the world. They are not damaged women, but survivors. And their strength does not lie in suppressing their emotions but in confronting them and adapting to them.

In Thunderbolts, emotions are not just ornamental but very operational. Thunderbolts lets its characters be all the things women are often denied on screen—emotional, inconsistent, and deeply human. In that messiness, there’s something precious: authenticity.

Feminism isn’t a detour—It’s the plot in Thunderbolts

In certain corners, there is a persistent complaint: Why is Marvel so very feminist now? The answer is simple because it makes the stories much more compelling. Women have been given more agency than they were in comic book storytelling. And Thunderbolts is a wonderful example of that. It thrives in identity politics. It’s a story about broken people navigating their broken system.

Feminism here is not sidelining men at all or spotlighting women for performative reasons. It’s about narrative texture. Yelena is not just a sidekick; she’s a moral compass. Ghost isn’t just angry; she’s trying to hold herself together, quite literally. Valentina isn’t just in charge; she’s an architect of chaos. These are well-written characters, and more importantly, they’re proof that feminist storytelling isn’t a detour from action. It’s what gives it weight. When stories take women seriously, not just as fighters but as people, it shows.

Thunderbolts: A universe big enough for all of us

Thunderbolts is not only a radical departure from Marvel’s legacy, but it also offers a new and fresh direction. In Thunderbolts, women are not framed, simplified, or saved but centred. It shows us that strength comes in many forms: in grief that does not break you, in plants that go unseen, and in bodies that heal on their own terms. We are not only watching women step into their own power, but we are watching them redefine it and that too on their own terms. And that is not just good feminist storytelling; it’s good cinema. MCU, which was once narrow and exclusionary, is now capacious enough to reflect the real world and all its complexities. This is no longer a world built just for the few—it’s a world for all of us.

About the author(s)

Juhi Sanduja is an Editorial Intern at Feminism In India (FII). She is passionate about intersectional feminism, with a keen interest in documenting resistance, feminist histories, and questions of identity. She previously interned at the Centre of Policy Research and Governance (CPRG), Delhi, as a Research Intern. Currently studying English Literature and French, she is particularly interested in how feminist thought can inform public policy and drive social change.

Powerful read! You captured Marvel’s evolving approach to feminism with clarity and impact. No tokenism, no clichés- just layered, commanding women leading the story with purpose. Insightful, timely, and expertly unpacked.