When FII asked Shazia Iqbal why she chose to adapt Mari Selvaraj’s Pariyerum Perumal for Hindi-speaking audiences, she smiled and explained in her straightforward, passionate way about cinema, ‘Adaptation isn’t copying. It’s reimagining. You take the story’s soul and rebuild the world in another language and culture while keeping your own voice.’ This insight, shared during our conversation, is the essence of Dhadak 2. It highlights why this film, though it draws comparisons to its source, feels like an original work of conviction.

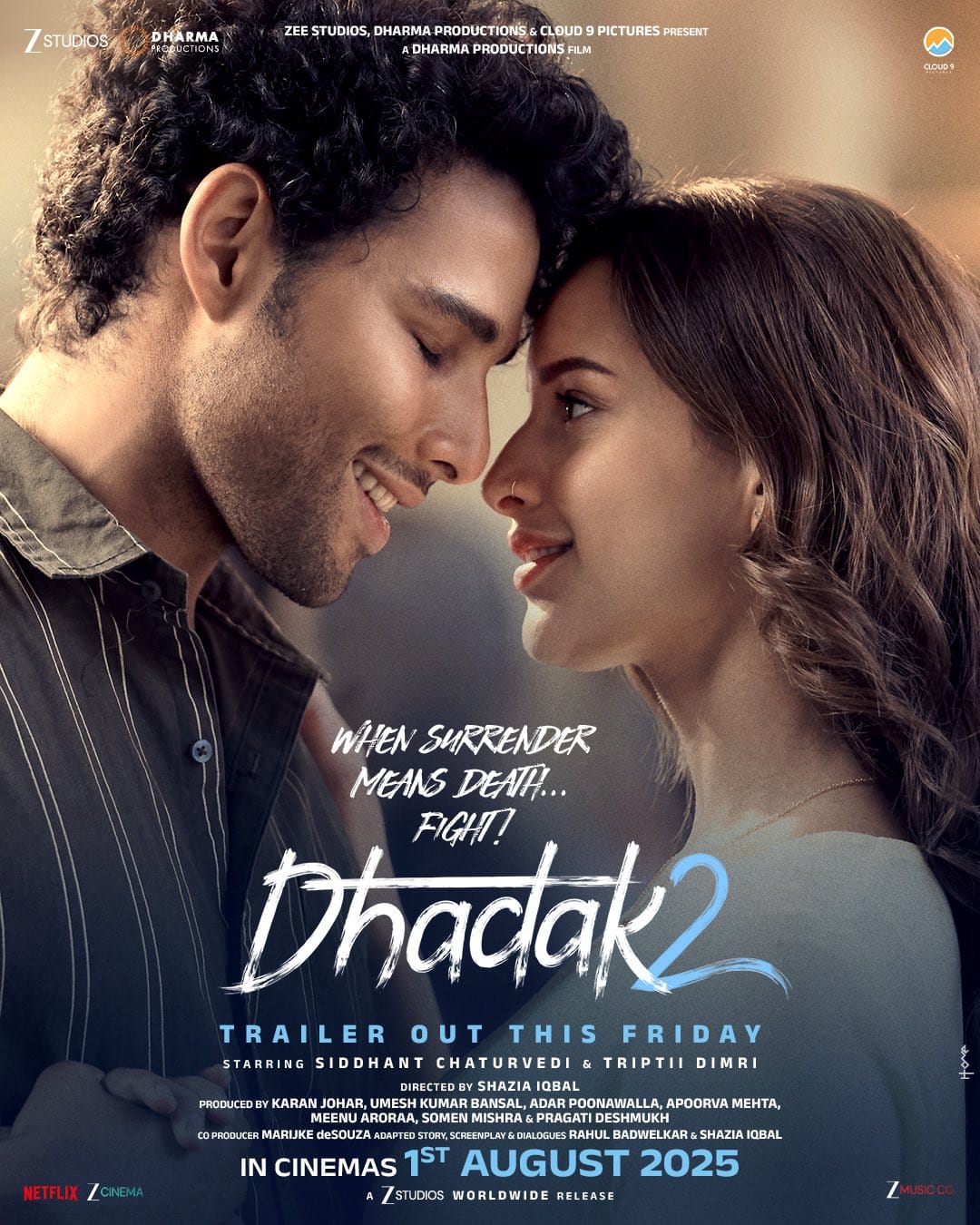

When Sairat had previously become Dhadak, the result was a glamorous film that lost the original’s edge. Dhadak 2 does the opposite. Based on Pariyerum Perumal, it maintains the original’s moral foundation but reshapes the details — altering focuses, reframing conflicts, and giving us two fully developed protagonists instead of one stereotypical hero. The film opens with a line that establishes its moral stance: ‘When injustice becomes law, resistance becomes duty.’ However, Shazia’s Neelesh (Siddhant Chaturvedi) is not a warrior but a quietly hurt young man facing his own internal battle with resistance.

The characterisation of Dhadak 2

This is a coming-of-age story about shame and learning to be seen. Neelesh’s poverty isn’t just financial; it’s about being socially invisible due to caste. He must stop hiding his surname in a classroom filled with Guptas and Agarwals. He must stop apologising for his English and his place in the world. Yet, his transformation isn’t an immediate shift to outrage. It’s a slow, stubborn process, and Siddhant plays it with subtle, impactful details — the flinch before he speaks and the way he gauges his laughter. When Neelesh finally erupts, it resonates. It comes from careful buildup, not cheap melodrama.

Shazia also cleverly makes Vidisha (Tripti Dimri) not just the object of Neelesh’s affection but a co-lead with her own struggles. In the original, she was more symbolic; here, she is real: prickly, self-aware, and determined not to be defined solely by marriage or her family’s name. Tripti gives Vidisha practical courage; she researches, questions, and demands answers. Her journey involves learning to articulate the injustices she sees and refusing to stay silent within her family. ‘I wanted their love story to be about two fighters,’ Shazia told us. ‘Neelesh fights his shame and fear. Vidisha fights against how her world defines her by gender. Giving her that agency was crucial.’ The outcome is a love story that resists easy simplification, showing that tenderness and political awareness can coexist.

There are thoughtful structural choices throughout the screenplay by Rahul Badwelkar and Shazia Iqbal that keep the film engaging. While Pariyerum Perumal opens with a personal tragedy and then introduces the enforcer of caste rules, Dhadak 2 starts by presenting society and the predator among them. We meet the assassin early and see him casually move through Neelesh’s life; the private cruelty, represented by the dog being killed in the original, becomes a recollected memory later. This choice forces viewers, especially those who may feel detached from the story — the more privileged audience members — to learn about the atrocity at the same time as Vidisha. It’s a clever way to bring the viewer’s ignorance into line with Vidisha’s awakening.

The screenplay also introduces Shekhar (Priyank Tiwari), a Dalit student leader who expands the film’s political context. He attributes his college admission to reservation policies, delivering one of the film’s most compelling lines: when Neelesh claims he’s ‘not into politics,’ Shekhar responds, ‘You entered politics the day you were born.’ This small exchange carries significant weight: caste is not a topic to be politely overlooked; it’s the structure of daily life. Shazia stated, ‘Caste is rarely discussed in Hindi cinema, yet it shapes so much of daily life. I didn’t want to touch the soul of the original, but I also didn’t want to ignore that Hindi audiences need to hear these conversations.‘

Shazia stated, ‘Caste is rarely discussed in Hindi cinema, yet it shapes so much of daily life. I didn’t want to touch the soul of the original, but I also didn’t want to ignore that Hindi audiences need to hear these conversations.‘

Casting and character design were areas of thoughtful consideration and some controversy. Shazia shared candid insights about the auditions for Dhadak 2: she and her writer had an afternoon meeting with Siddhant; he listened, connected with the vision, and agreed to join within an hour. She admitted she hadn’t realised his complexion at the time — ‘I didn’t know Siddhant was fair,’ she said — but insisted on a specific aesthetic: ‘I love brown skin on men. I didn’t want him to be a fair-skinned hero. We kept asking: Why will she fall for him? The answer couldn’t be about skin.’ This principle is vital to the film: a romance that isn’t validated by conventional beauty standards.

Confronting criticism: an opportunity for dialogue

When critics mentioned “tanning” or accused the film of superficial tricks, Shazia responded with a balanced, not defensive, tone. She pointed out that casting and character design are separate decisions and highlighted the film’s production choices: ‘People in the makeup and hair department come from the community. The lead makeup artist is from the community,‘ she told us, emphasising the production aimed for community involvement rather than appropriation. ‘I understand the hurt,‘ she said, acknowledging Bollywood’s history of poor representation. ‘That’s why you need to at least talk to the director to grasp the intention and choices.‘ Her tone invited dialogue rather than dismissing critiques.

The film is technically polished in all the right ways. Sylvester Fonseca’s cinematography is understated yet precise; he captures the characters’ inner worlds over flashy visuals. The film maintains a sober, almost documentary feel in the way it portrays the colony, college, and domestic spaces. The camera often keeps a measured distance, closing in during moments of humiliation or violence. The only misstep is the score, which sometimes shifts toward melodrama, undermining some of the film’s quiet intensity. The best scenes feature no music at all, like the moment Vidisha’s father speaks after his son-in-law’s humiliation; the silence amplifies the weight of his words.

Performance-wise, Dhadak 2 is impressively cast. Siddhant Chaturvedi carries the emotional weight of the film with a believable intensity; his shyness feels genuine, not like a performance. When he finally lets go of that restraint, we feel the impact. Tripti Dimri shines with a stubborn light; she imbues Vidisha with warmth that never becomes too soft. Anubha Fatehpura as Neelesh’s mother portrays a quiet, formidable dignity — a glimpse of a woman who has fought long before her son learned to fight. Priyank Tiwari, Saad Bilgrami, Vipin Sharma, and Zakir Hussain round out the cast with performances that create a sense of a lived community rather than mere character types.

Priyank Tiwari, Saad Bilgrami, Vipin Sharma, and Zakir Hussain round out the cast with performances that create a sense of a lived community rather than mere character types.

There are times when Dhadak 2 seems a bit preachy — a trap that socially conscious cinema often falls into. A scene between Shekhar and a pen comes off as awkward in its symbolism, and the hopeful final image doesn’t always feel completely warranted. Still, these are minor flaws in a film that is otherwise thoughtful and deliberate in its moral vision.

Dhadak 2 deserves praise for presenting women’s rage without reducing it to clichés. Vidisha’s scream — a public outburst — is shown not as hysteria but as a moral stand. It’s both cinematic and political: a declaration that private feelings are also public truths. ‘Her scream is loud enough to stop a bullet; it is a reaction to her surroundings, and not meant to be gimmicky,‘ Shazia noted, emphasising the importance of hearing it.

Shazia spoke candidly about the challenges of adaptation. ‘Adapting is harder than creating an original,‘ she said. ‘When you write your own story, you know exactly what you want to convey. Here you’re taking someone else’s voice — the original director comes from a marginalised community and has a strong voice — and you must honour that spirit while fitting in your own.’ That balancing act is exactly why Dhadak 2 is important. It neither overshadows nor diminishes Mari Selvaraj’s film; it engages with it. What it achieves is a Hindi-language complement that reorients the story for a new audience without losing its political essence.

Beyond box office success: telling impactful stories

Finally, Shazia acknowledged that box-office numbers don’t tell the whole story. ‘In theatres, our film isn’t performing as well as we hoped,‘ she said. ‘But there’s so much word-of-mouth — reels, conversations. People are calling it a film that needs to be seen, which feels good.’ This mixed reception reflects a broader reality: films that challenge established narratives take time to resonate. Some viewers will catch on later, when the discussion evolves into understanding.

Dhadak 2 may not hit as hard as Pariyerum Perumal — its anger often simmers rather than bursts — but it accomplishes the difficult and brave task of turning a regional story into a film that communicates effectively in another language to a new audience without sacrificing its moral core.

Dhadak 2 may not hit as hard as Pariyerum Perumal — its anger often simmers rather than bursts — but it accomplishes the difficult and brave task of turning a regional story into a film that communicates effectively in another language to a new audience without sacrificing its moral core. It expands, reframes, and emphasises female agency; it places caste discussions where Hindi cinema frequently avoids them; and, crucially, it does so with skill and care.

This isn’t just a showcase for stars. It’s a statement from the director — one that acknowledges its responsibilities to the source material, to the community, and to truthful storytelling. As Shazia concluded our conversation: ‘You become emotionally engaged with the film when you treat it like worship — you protect it, you don’t want it destroyed. That’s how I felt while making this.‘ That feeling translates to the screen. For a cinema that often prefers comfort over confrontation, Dhadak 2 is a welcome and necessary disruption.

About the author(s)

Harshi is a writer and LGBTQ+ rights activist. She is also a self-identified singer. Her preferred pronouns are she/they and she identifies as a Non Binary Transwomxn. Raised to be someone who should just accept the norm , she has spent the last decade reading and writing about eccentric people and their experiences around her. Harshi has completed B.A.(HONS.) English from the University of Delhi and M.A. in English from Amity University. She cautions anyone who is thinking of doing the same. She thinks she is a realist, she still hopes to see some good change in the history of Human Rights in her country with a little contribution from her writing and activism. You can find her on Instagram- iamharshib.