The female body has always been a site of violence in the social setup of India. The lesson on “bad touch/good touch” is not learned through the workshop manuals in schools but sadly lived through experience by young girls. Whether it’s the bazaars, buses, streets, metro compartments, educational institutions, public washrooms, or crowds, can a female body ever feel truly safe anywhere in India? Homes the least. NFHS‑5 estimates that nearly one in three ever‑married women in India faced domestic violence from their husband in just the previous year, while NCRB’s 2023 data shows ‘cruelty by husband or his relatives’ remains the single largest category of recorded crimes against women, with over 1.3 lakh cases. The mere pronunciation of “home” is repelled with aching memories of violence manifested in deep scars on the body that remain for a lifetime as reminders of conflict, unrest, shame, guilt, anger, and the costs of survival.

So when we caress our conflict-affected bodies with strokes of colours that we choose, drawing designs using techniques of our own volition, we transform the body from a place of violence to that of autonomy, self-acceptance and therefore, liberation. Feminist research on body modification shows that when women choose tattoos and other forms of body art on their own terms, these marks can become “reclamation through alteration of the body,” turning stigmatized skin into a chosen archive of survival and self‑definition. Work on South Asian women’s tattoos similarly traces how women’s tattoo practices intersect with waves of feminism in the region and with resistance to gender norms that police how a “good” woman’s body should appear in public.

Body art as more than self-expression

Body art plays a role beyond self-expression; it is a powerful tool of resistance against oppressive standards of beauty (and therefore being) that are shoved down our throats every single day. We walk looking at the skyful of billboards of faces that are advertised as the standard we should dream to match but will never be; a gap – an insurmountable gap – is drawn from the walking self to the female self high up on those billboards, bodies of seemingly unmatched beauty possible to copy only through consuming a certain product and following the exact gazillion steps of a routine a celebrity swears they do not step out of their house without doing. Yes, you NEED those exact gazillion products if you are serious about being beautiful – aka fitting into the beauty standards acceptable by these companies who profit from our unacceptance, our unwillingness to accept our body as it is, or our unwillingness to hug our scars.

The argument of purity used so readily by conservative Indians to retaliate against body art is nothing but just the age-old violence perpetrated on our bodies.

The extra bulge in your lower belly – you should hate it; the chubby cheeks – how dare you post selfies with those? Go on a water diet and cut down all the sugar; the textured skin up close – that is an unnatural sight, but it can be minimised if you use this exact product, which is a little up the price range, but at least you will be beautiful then.

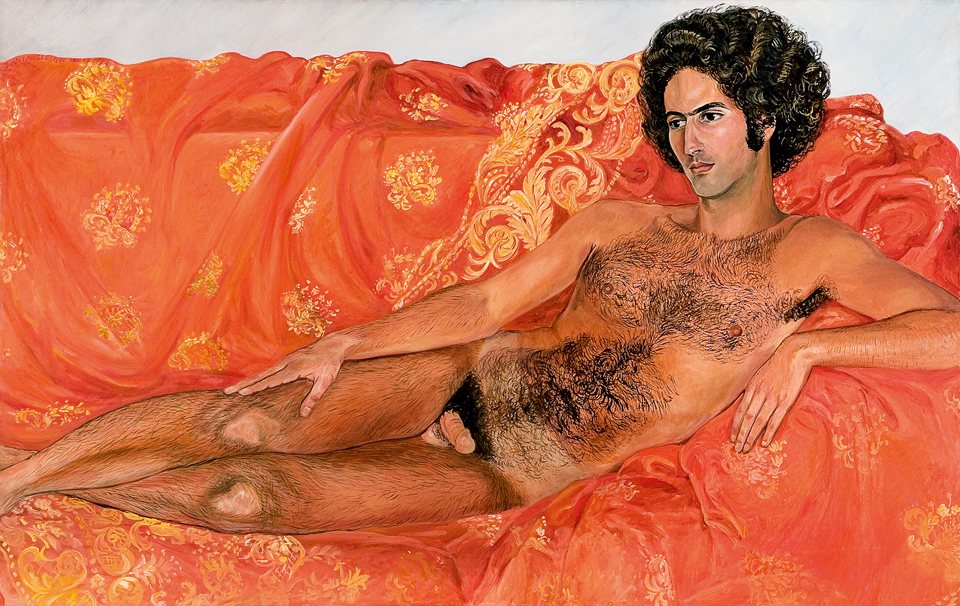

Then we draw beautiful moons, sunflowers, butterflies, angels, lilies…on the exact waist, shoulder, and legs, with each stroke of the brush drawing not just art but piercing together love across our body, reviving our lost sense of selves, reiterating that we – our natural bodies – indeed are beautiful, that the body is a house of memories, yes, but all of it is beautiful because you have surpassed all of the hate perpetrated on you, you are here, and you are beautiful. It is a strong way of telling consumerist behaviour put forth by money-making scams romanticised as the beauty industry that we do not buy into this self-hating façade; we do not need those overpriced, skin-shade-changing, texture-changing beauty products.

Female bodies resisting oppressive norms

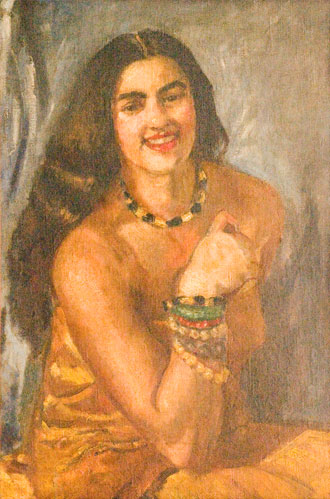

This form of resistance and self-expression has helped so many of our grandmothers whose voices we never heard beyond “yeses” in the household; their mouths might be silent, but we see the tattoos on their wrinkled skin tell a story of revived youth, tattoos of signs and symbols they hold dearest to their hearts. As feminist scholars note, this is a kind of reclamation work, where women take skin that has been a site of judgement and hurt and mark it with symbols they choose for themselves.

When I look at a grandmother’s wrinkled arms and see stars, flowers, deities and initials, I’m reminded that their bodies have been doing this quiet reclamation long before we had the language for it.

When I look at a grandmother’s wrinkled arms and see stars, flowers, deities and initials, I’m reminded that their bodies have been doing this quiet reclamation long before we had the language for it. It’s not just a cool sight for us Gen-Zs to feel closer to our grandmothers, who we now find are cooler than we gave them credit for, but it shows that their bodies have also resisted oppressive treatments and the constant dictation of the consumerist world and the patriarchal society on what we are lacking, what we should be, what we should strive to be, and how and in what parts our bodies are beyond the acceptance of love. Younger South Asian women today use tattoos to mark queerness, grief, faith and friendship on their own skin, staking out space for messy, complicated selves that do not fit into the respectable “good girl” norm.

Even literary forces have eulogized the power of body art in liberating the female body. In Han Kang’s “The Vegetarian”, critics read Yeong‑hye’s marked, plant‑like body – covered in painted flowers and trees – as both the canvas of patriarchy’s violence and her only remaining site of protest, a radical but costly bodily world‑making. When I read the novel, the most impactful part of the story that stayed with me was the scene when our protagonist, in the midst of her new identity change, has flowers and trees drawn over her weak naked body; it brought liberation to not just her (the poser), but that sense of transformation was brought across the pages to us (the readers). That was art.

Even the argument of purity used so readily by conservative Indians to retaliate against body art is nothing but just the age-old violence perpetrated on our bodies, the ideas of body purity put forth by “society”. As Maya Angelou writes in her book, ‘Gather Together in My Name’, “Society is a conglomerate of human beings, and that’s just what I was. A human being,” she refuses to let “society” remain an abstract, faceless force, reminding us that society is simply made up of other human beings who do not want to cope with our full humanity.

To the society that loves to stay bound and blinded within the metal cage of patriarchy and oppression, to that we say – resist and self-accept; here we are, our true, beautiful selves moulded with art; we are art.