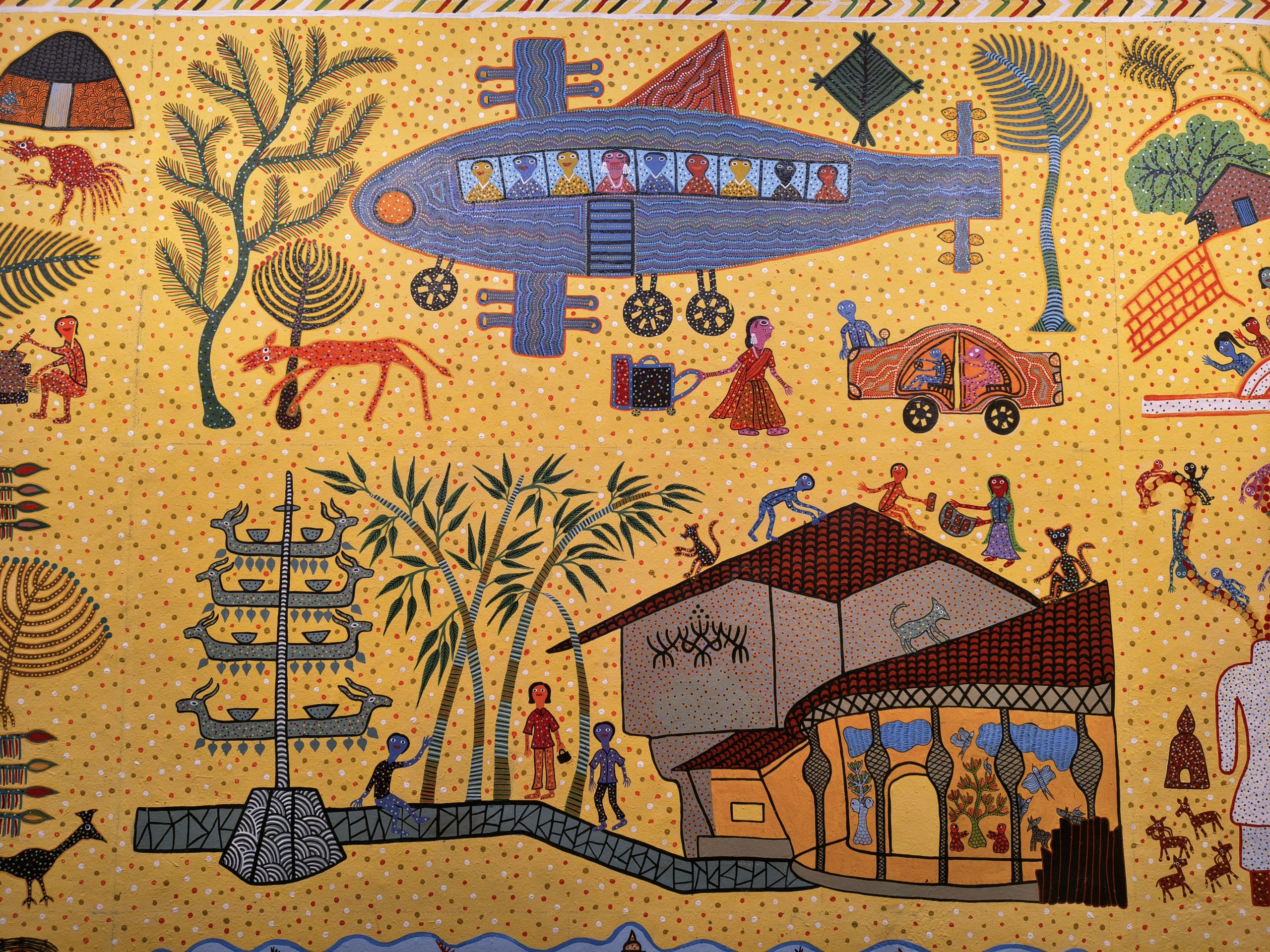

Domestic art in India has always seemed harmless, from a dusting of colour on the floor, a white line on cool red oxide or a delicate pattern your mother’s fingers can expertly draw in the dark. Yet these decorations allow women to rewrite narratives on who gets to speak, who gets seen, and where the line between obedience and rebellion is drawn. Rangoli, alpana and kolam together form a visual language through which women have blessed homes, negotiated patriarchy, and, increasingly, staged dissent.

Domestic art in India can be broadly understood as the visual designs and motifs created in and around the home on floors, the main door and inner courtyards using everyday materials like rice flour, coloured powders, flower petals or paste. It includes rangoli (widely practiced in western, central and northern India), alpana (especially in Bengal and eastern India) and kolam (predominantly in Tamil Nadu and parts of South India), among many other regional variants.

Three Sisters of the Threshold: Rangoli, Alpana and Kolam

Rangoli often bursts with colour such as marigold yellows, sindoor reds, electric blues drawn during festivals and weddings to welcome Lakshmi, guests and prosperity itself.

Alpana in Bengal usually appears as white patterns painted with rice paste, featuring lotus motifs, goddess feet and conch shells on floors before Lakshmi puja or Annaprashan, turning the home into a temporary shrine.

Kolam is made by dropping and dragging rice flour into intricate looped designs outside thresholds at dawn, tied to ideas of auspiciousness, cleanliness, community and femininity in Tamil culture.

All three share certain traits. One: they are mostly made by women. Two: they are repeated daily or ritually, seen more as a routine duty rather than art, and three: they sit on thresholds, or the exact point where the private and the public meet. That threshold is not just architecture; it is a stage of performance. The woman who bends down with a bowl of powder is not only cleaning and decorating. She is also, knowingly or not, writing her part in the larger script of gender, respectability and power.

Parallel Lines: Who crosses and who is caged?

Consider perhaps the most famous line in Indian popular imagination: Sita’s Lakshman rekha. In the original tale, Lakshman draws a line around the hut, a magical boundary Sita must not cross. Feminist critics read this line as a metaphor for the bounds of morality which are constantly imposed on women – a bound which claims to keep danger out while in fact keeping a woman in. Contemporary authors like Volga and Amish Tripathi reimagine Sita as crossing that line not out of foolishness but as an act that exposes how rigid moral codes police female agency.

Now place that mythic line next to the very real, everyday lines of rangoli, alpana and kolam. These lines also circle thresholds, frame doorways and mark limits but more crucially, they are drawn by women. Instead of a brother guarding a woman’s purity, a woman herself has the free will to mark the entrance of her home with her own hands, day after day. The boundary is still there, but it is for her to redraw every morning.

Take for instance when a Bengali woman paints alpana footprints of Lakshmi walking into the house, she is deciding where prosperity enters, how it moves and what it looks like. The line is not a cage; rather it is choreography. Or how a woman in Chennai draws kolam that spills beyond the official doorway onto the street, gently pushing the domestic boundary outward, claiming public space with rice flour.

Popular culture keeps returning to the Lakshman rekha as a warning against women who may be crossing their limits, while feminist rewritings insist that Sita’s crossings expose those limits as unfair. Domestic art creates a counter-image: the line is able to protect because it is self-drawn, erased and redrawn. The same culture which gives Sita a line she must not cross also gives millions of women lines they control, even if the world insists on calling them just decoration, with over 85% of urban households still practicing rangoli during festivals.

Where the Ideal Woman is Drawn on the Floor

Indian visual culture, from 20th‑century calendar art to Bollywood set design, takes this domestic aesthetic a step further. The ‘ideal home’ on screen is thick with visual cues: an ever present rangoli in the courtyard, framed gods, flowers on the door and diyas along the steps. The camera often lingers on these details to signal that this household is teeming with sanskaar, warmth and femininity, even before any character has the chance to speak.

Think of how many films introduce a dutiful daughter-in-law or mother with a shot of her making rangoli or lighting a lamp with her bent posture and careful movements, telegraphing care and humility, along with her skills in making a perfect rangoli which is also a stand in for her ability to keep the family together. This reflects a lot of how real-life institutions too mobilise rangoli as a symbol of “good womanhood” and empowerment: Women’s Empowerment Cells in Indian colleges routinely organise rangoli competitions during Navratri or Sankranti to provide a platform for women to showcase their artistic talents and promote gender equality and community spirit.

Even when cinema and campus culture use domestic art as shorthand for something which makes a good woman, there is a subversive potential. If rangoli is the badge of ideal femininity, then the woman who plays with it can quietly hack that badge.

How Decorations Learns the Art of Argument

Social media is full of reels and images where people create Women’s Day rangoli with messages like ‘Stop Violence Against Women’ or justice-themed designs, turning a nice tradition into direct commentary. Once you give women a visual language, they do not keep to the script forever.

On the surface, rangoli, alpana and kolam are deeply tied to patriarchy: they are unpaid labour, often expected from women as proof of dedication to the family and gods. Skill in these arts has even been assessed as a trait of marriageability in some communities, where a neat, complex rangoli is read as evidence that a woman is disciplined, patient and responsible – judged during matrimonial processes in Tamil culture.

Domestic art becomes a feminist language in at least three ways.

Firstly, by giving women control over space. The area outside the front door may legally belong to a man or the state, but daily it is visually claimed by the woman who draws on it. With each design drawn she says: this is my threshold and this my mark.

Next, it is the culmination of time these women have carved out of chores. Waking early to draw a rangoli may be often framed as duty, but it is also a sliver of time where women are alone with their thoughts and art. Anthropologists note that kolam-making is often the first act of a woman’s day, with surveys of 312 Tamil artists showing it as a matrilineal tradition tied to womanhood – yet it also offers a fleeting moment of self-directed creativity before other demands flood in.

Finally, it gives them an individual voice inside the bounds of tradition. Even within strict conventions (certain motifs for certain festivals, rules about symmetry, colours and measurements), women innovate. Studying these daily aesthetics highlight how women alter patterns, integrate initials or local jokes, and borrow imagery from cinema or politics, expressing individual style under the guise of continuity.

There have been moments when domestic art has dramatically burst out of the threshold and into overt protest. In late 2019, after police denied permission for an anti‑CAA gathering in Chennai, a group of women in Besant Nagar drew kolams on the street with slogans like “No CAA,” “No NRC,” and “No NPR.” The women were briefly detained, turning these ‘just kolams‘ into front‑page news and demonstrating how dangerous little rice flour can look, spelling out dissent.

The protest did not stop there. The DMK’s women’s wing was later asked to draw kolams outside their homes with “NO CAA, NO NRC” slogans, and DMK president M.K. Stalin had a kolam with “Vendam CAA‑NRC” (Don’t need CAA‑NRC) drawn outside his residence. Commentators described how this very auspicious and traditional kolam had become a political tool in the hands of female citizens, a visual form that could travel from doorstep to protest site without losing its cultural legitimacy.

Anonymous Hands to Art History: the Pipeline

While domestic artists typically remain unnamed, organized events and art histories are slowly foregrounding their significance. College and community rangoli competitions for women, such as Sankranti events run by Women’s Empowerment Cells, explicitly frame rangoli as a vehicle for “self-expression,” “community bonding” and women’s confidence.

At the level of “capital‑A Art,” feminist histories of Indian art track how women artists push back against male‑dominated canons often by engaging everyday and domestic imagery. Writers chronicling ‘feminism in Indian art’ point out how figures like Amrita Sher-Gil, Mrinalini Mukherjee, Nalini Malani and Anita Dube draw on women’s bodies, domestic labour and vernacular forms to challenge the male gaze and nationalist mythologies. Nalini Malani’s installations, for instance, layer mythic women like Sita with contemporary images of violence suggesting that the ‘vanished blood’ of women’s histories still stains the present.

These artists rarely reproduce rangoli or kolam literally but their work belongs to the same feminist impulse: taking that which was coded as soft or private or feminine and revealing it as intellectually and politically charged. The gallery becomes an echo of the courtyard; the installation, an amplified, historicised rangoli that refuses to be swept away.

Here, and Gone Like a Good Secret

One of the most striking things about these forms is that they are meant to disappear. People walk over them, brooms cut through them and raindrops dissolve them. The design is gone by evening or the next morning. At first glance, this seems like a weakness; if it simply does not last, how important can it be?

Ephemerality is part of the power. It refuses ownership. A morning alpana drawn with rice paste cannot be auctioned or archived like a painting. It belongs to whoever encountered it in that brief window. Even when kolam patterns inspire digital design or algorithmic studies, the original practice resists being fully captured because its life is in repetition, not permanence.

It also demands repetition. Because it fades, it must be remade. Feminist protest here is not one grand spectacle but a thousand small gestures. It is even able to undercut monumentality. Patriarchal and nationalist power loves statues, massive paintings and giant portraits; things that loom and last. Domestic art says power can also be soft, temporary and at ankle level, forcing people to literally watch their step.

A rangoli expects that you look down carefully and not crush someone’s labour and faith. It trains the body into tiny acts of respect. That is a different, quieter kind of power, but no less real.

A statue demands that you look up. A rangoli expects that you look down carefully and not crush someone’s labour and faith. It trains the body into tiny acts of respect. That is a different, quieter kind of power, but no less real.

In contemporary India, domestic art constantly travels off the floor and onto phone screens, fashion and even tech. Photos of morning rangolis circulate on family WhatsApp groups, turning once hyper-local designs into widely shared images. Designers and HCI researchers have studied kolam as “ecofeminist computational art“, noting the algorithmic logic of its patterns and the gendered knowledge embedded in their creation.

Rangoli, alpana and kolam are sophisticated systems of design tied to cosmology, community, ecology and gender. They are also, crucially, performances: the art lies not only in the finished pattern but in the act of making it, right from the posture, timing, conversation and who is allowed or expected to do it.

Redrawing the Rekha

The Lakshman rekha story imagines a woman shut behind a male‑drawn line. Feminist retellings show Sita stepping across, refusing to accept that her world must be so narrowly drawn. Domestic art, au contraire, shows countless women stepping right up to the line, tracing it themselves, colouring it, bending it and sometimes quite literally writing their refusal into it. The line here does not just contain them; they use it to frame the world on their own terms.

Domestic art in India is often treated as the background, it may be nice for photos or good for festivals, but is essentially expendable. In reality, it is the opposite: it is the script, the stage and sometimes the scandal. Every alpana, rangoli and kolam takes the logic of Lakshman’s rekha: a line drawn to discipline a woman, flipping it into a line drawn by women for themselves, across which they invite gods, neighbours, gossip, protest and change to step.

In a culture obsessed with who crossed which rekha, these women quietly redraw the map. Their lines bless and they bite; they welcome and they warn. What looks like powder on the floor is, in fact, a daily referendum on who belongs, who decides and who dares to speak.

Comments: