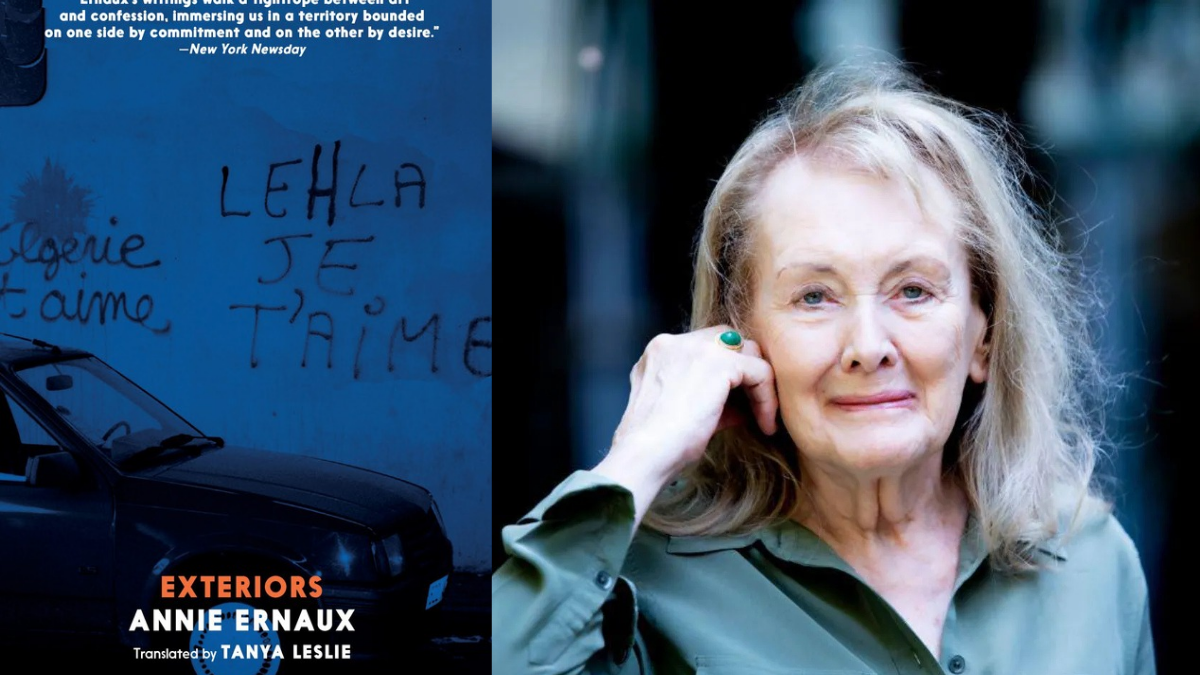

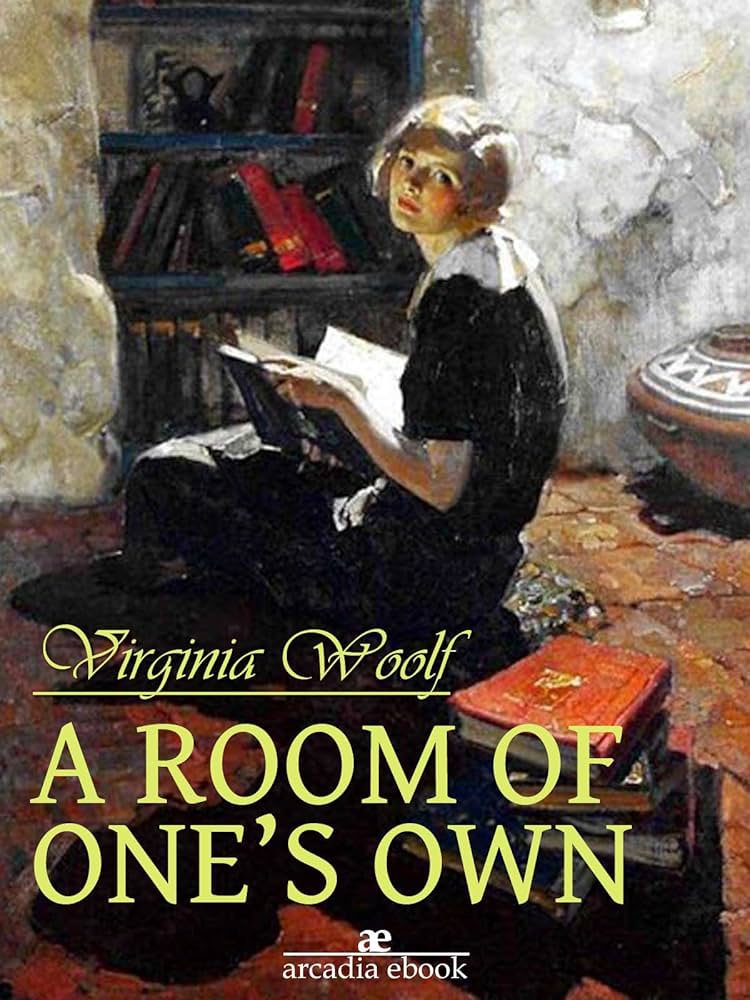

In her famous speech-turned-essay titled A Room of One’s Own, a work that is now considered a seminal piece of feminist literature, English writer Virginia Woolf argued that “a woman must have money and a room of one’s own” if she is to write fiction or undertake any intellectual pursuits. Woolf’s words have resonated so deeply with women across time and space and are often brought up in conversations about gender inequality because they highlight the link between a lack of ownership over material resources and the marginal position accorded to women in society. Zeenath Sajida, an Indian writer and academic, explores the same idea as Woolf but from a different perspective in her writings.

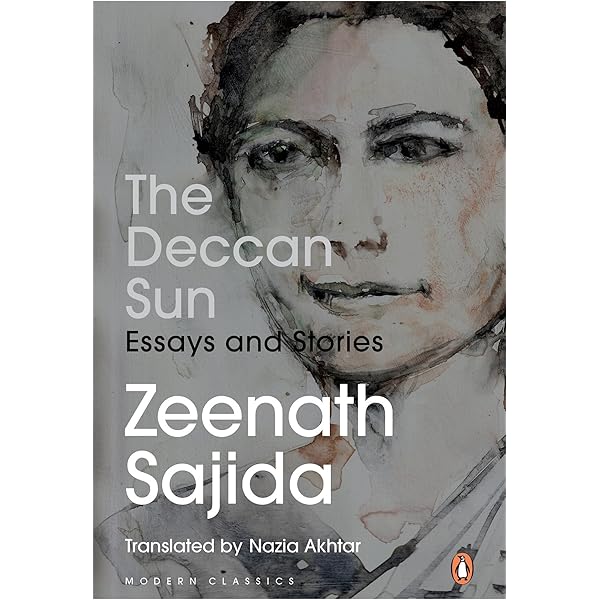

Best known for her incisive prose and her sharp-witted khaake (pen portraits) and inshaaiye (light sketches), Zeenath Sajida is considered to be one of the most influential female writers of Urdu literature. The Deccan Sun, translated by Nazia Akhtar and published by Penguin India in 2025, is a collection of essays and short stories Sajida wrote in the mid-twentieth century. In the short stories, sketches, and essays featured in this collection, Sajida paints a vivid picture of Hyderabad where she grew up and holds a mirror to the socio-political realities of her time, particularly focusing on the everyday challenges and inequalities faced by women.

While Sajida’s writing is characterised by a strong element of playfulness and humour, it tackles serious themes such as gender inequality, women’s lack of agency and bodily autonomy, the restrictions and burdens placed on women’s shoulders, the invisibilization of their domestic labour and their consistent exclusion from public spaces and roles of power. Through her essays, Sajida gives voice to the many unsaid complaints and unheard pleas of women and advocates for equality in all spheres of life.

Women cannot be prophets

In ‘So Long as I Exist, There Will Be Obstacles in My Path’, the first essay in this collection, Sajida makes a provocative statement, declaring that women ‘could never be prophets’ like men have been throughout history. While a comment like this might be misinterpreted as being borne out of a sense of internalised misogyny or inferiority, a closer reading shows that Sajida’s proclamation is based on sheer practicality.

Prophethood makes for an unfit calling for women, in Sajida’s view, because to become a prophet, one must have time to sit, think and ponder—a luxury that most women, especially those in the Indian subcontinent, cannot afford. Women already have so many responsibilities on their shoulders and so many duties to fulfil that taking on the added ‘burden’ of prophethood would only cause more problems for them. In a patriarchal societal setup, where women are expected to take care of all aspects of the household and cater to all the needs of their families, there is no time left for women to undertake any larger-than-life mission.

Prophethood is simply an extended metaphor Sajida uses to show the lack of control women have over their time and lives. Let alone become a prophet, a woman cannot even achieve mastery over worldly things such as cooking, sewing or painting because mastery requires consistent practice and time to develop the skill. Even in the hypothetical scenario Sajida presents, in which a woman attempts to receive a divine revelation in a cave, her focus is broken by various members of her family, who want her to help them with something or the other. And when the woman finally gets a chance to ‘breathe a sigh of relief, divine revelation has sailed past Makkah and Madina.’ Interruptions, Sajida suggests, are a routine part of a woman’s existence.

While it would be easy to dismiss the issues being raised by Sajida as problems of the past or as challenges that only Muslim women living in Hyderabad of the 1940s and 1950s faced, recent research has shown that women, from diverse backgrounds and varying contexts in India, disproportionately bear the burden of doing household work today. The Time Use Survey, conducted by the Government of India in 2024, revealed that 81.5 percent of women in India perform unpaid domestic labour as opposed to only 27 percent of men; and on average, a woman spends 289 minutes performing unpaid domestic services for family members every day, while their male counterparts only spend 88 minutes doing the same. Reports like these only reaffirm that the gendered division of labour and a lack of leisure time for women are problems that have existed for ages and that still persist today.

Job or no job, women are doomed either way

Sajida’s work also explores the double-edged sword that women who want to pursue careers and lead lives outside the home face. In the essay ‘I Got Myself a Job’, Sajida shares the dilemmas she faced when she started working. Her job drained all her time and energy, leaving her with no desire to do anything creative or recreational, and even after coming home, she could get no respite from ‘the snare of work’ as she was expected to do household work.

Highlighting the unrealistic demands placed on women who work, this essay stresses that being ambitious and career-driven are qualities celebrated in men and deemed undesirable in women. Women who prioritise their careers are seen as selfish and arrogant. Sajida writes about the resentment and scorn directed her way by her family and friends, who, instead of sympathising with her or appreciating how she was juggling work and domestic chores, were quick to complain because she could no longer be at their beck and call.

While having a career should ideally feel liberating for women, it often becomes an added source of woes and worries in patriarchal societies. The woman, trapped between work and home, becomes like the caged bird that returns again and again to its prison—even after it attains freedom—and hits its head against the cage.’

Always ‘someone’s something’, never a person in their own right

The Deccan Sun also highlights how women are devalued and only as ‘someone’s something’—a woman is X’s daughter, Y’s wife or Z’s mother, not an individual in her own right. While a man is seen as a complex person with a fully developed personality and given the freedom to chase after his dreams, a woman has to ‘consider her mother’s tears, father’s honour, brother’s threats, child’s voice, family name and dignity of her community’ before making the smallest decision.

In ‘If I Were a Man’, Sajida ruminates over how life would have been extremely different for her, and for other women, had they been afforded the same privileges and freedoms that men are granted. She lists the things that she would be able to do if she were born as a man, things that women could never get away with doing, such as wasting time at home without being expected to cook or clean, going on dates and sleeping with whoever they liked without judgment, roaming around late at night and exploring the world with no fear.

Sajida argues that if she were a man, she would also “be a slave to her appetites” and follow a hedonistic lifestyle and present herself “as a freethinker” as a lot of men do. By drawing attention to the many ways in which men and women lead different lives, this essay offers a powerful critique of societal norms and social attitudes that limit women’s freedoms, deprive them of the small joys in life and force them to fit into the narrow moulds and ideals created for them by others.

Sajida’s exasperation and rage with sexist double standards fiercely shine through this piece and is also visible in the tongue-in-cheek advice she gives to young women:

“When someone says that a woman has not achieved mastery over any art, please scratch them across the face. And tell them to spare one room and one day of leisure [to the woman]!”

Women in search of a room over the years

While it can be hard to imagine what a woman from 1920s England, a woman who spent her youth in Hyderabad of the 1960s and a woman who is living in New Delhi in 2025 could possibly have in common with each other, there are several common threads that bind women’s experiences and lives across time and space.

Despite decades having passed and the world undergoing all kinds of changes since Sajida wrote these essays, women in India and elsewhere are still fighting to get the same opportunities, recognition, freedoms and privileges as men. The 2025 International Booker Prize-winning Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq, Taylor Swift’s 2019 song ‘If I was a man,’ the 2021 Malayalam-language film The Great Indian Kitchen and its 2025 Hindi counterpart Mrs. are just a few examples of contemporary literature and popular music that shed light on the persisting gender inequalities and demand more representation and rights for women.

The room that Virginia Woolf, Zeenath Sajida and thousands of other women speak of and have been searching for is not just a physical place comprised of four walls, a writing desk or a window to look out of, although sometimes it can be that too… That room is a metaphor for every opportunity and resource that women have been denied and deprived of. It is a symbol for freedom, equality, and much more. So much more.