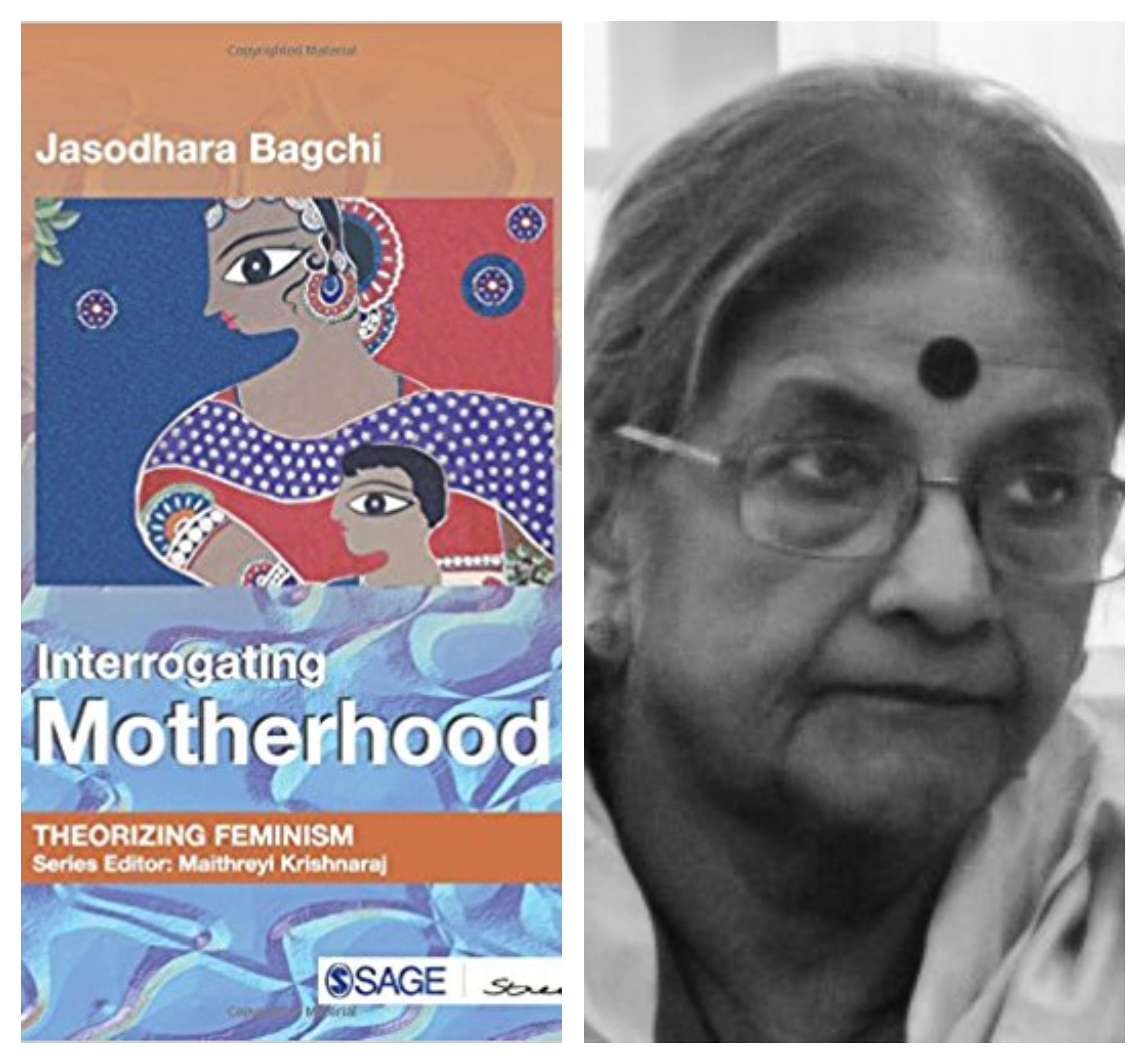

When an all-inclusive list of role-playing emoticons displays a woman with a child as a symbol of a caregiver, I wonder about the casual absence of the image of a man with a child, the father as a caregiver. An absence which reinstates how silently the concepts of mother, mothering and motherhood is played with by capitalist patriarchy so that these categories remain within their stereotypical constrictions. I read Jasodhara Bagchi’s, Interrogating Motherhood (2017) which tries to fathom the concept of ‘mother’, unearthing its contradictions, manifestations and realities, especially within Indian society.

While the analysis of motherhood as a gendered concept risks rejection of its human elements, it is also essential to unpack its inherent paradoxes. These paradoxes hide the powerlessness that silently lies beneath the glorification of motherhood. This glorification in turn legitimises oppression which becomes a lived reality for numerous women where motherhood ultimately becomes parched of its joyful meanings.

Interrogating Motherhood proceeds to a carry on with a feminist reading of motherhood which she considers essential for understanding how the global capitalist system is at work in making motherhood an exclusive site of glorification for women. The capitalist system penetrated India through the colonising project of the British rulers and continues to flourish within the growing reach of neo-liberal practices.

Bagchi explores the condition of women in colonial Bengal in detail to argue that motherhood becomes a tool of women enslavement when placed within the intersecting grid of state, family, culture, scientific and technological enterprises. As a mark of identification for the biological female, Bagchi opines, motherhood in India is intimately connected to the ideologies that helped in the nation-building processes during the colonial period and was further celebrated in the imagination of a post-colonial nation.

I wonder about the casual absence of the image of a man with a child, the father as a caregiver.

The colonisers manoeuvred the idea of a woman to civilise the brown/’native’ men and also to ‘save’ the brown women from brown men. Nationalist movements dovetailed the notion of ‘Mother Goddess’ with the nation in such a manner that the idea of the nation became analogous with mother/goddess.

In Bengal, the idea found a stronghold in varied manifestations of Goddess worship among social reformers like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee and Swami Vivekananda. Their clarion call to the sons/devotees of ‘Bharat Mata’, was to shake off sterile effeminacy and plunge into the Swadeshi movement to deliver the enchained mother goddess/land. Interrogating Motherhood analyses how these concepts gained entry into the private spaces of the middle-class homes to generate contradiction in the projected and practised images of mother/woman.

The private spaces witnessed a manipulated approach towards women’s education, which was encouraged only to equip women with the efficiency to raise sons for the nation by constantly percolating stereotypical ideas through generations. Thus, reproduction and nurture become patriarchal tools which are used to reproduce patriarchal ideas that would become the basis for more hierarchies.

The Hinduization of a multi-religious nation was insensitive as it denied representation to a large section of the non-Hindu population as well as Hindus from non-dominant castes, which could be considered responsible for the constant volatile communal situation in the country. These communal tensions have always seen women victimised beyond repair. This glorified image of the Hindu mother of a son directs intense viciousness against women who were forced to bear sons, abandoned if unable and subjected to multiple abortions.

Also Read: We Need To Stop Viewing Women As The Flag-Bearers Of Nationalism

While ‘tradition’ tries to trample women, women look for opportunities to soar high. This brings women into the public sphere where they try to strike a balance between their lives as mothers and working women. However, instead of being assisted in their efforts, these women are often snubbed and their agency often curtailed by an upper-class and upper-caste prejudice of mother-glorification which trashes working women as ignorant, unsanitary, negligent mothers who fail to perform their role in bringing up ‘quality’ sons for the nation.

When contraception was first introduced in India in the 19th century, motherhood encountered a renewed form of oppression at the hands of professionals in alliance with corporate capitalists. Although contraception was supposed to remove all constraints that women experienced, it has never, from its very inception, been able to grant autonomy to women with respect to childbearing and rearing because it is deeply situated in the politics of class, caste, religion and space.

Women once again became objects of biological experimentation. The personal freedom that Indian women would gain with the introduction of contraception underlined a suggestion of promiscuity which was “inconsistent with their dignity”, Gandhi opined. Although women’s movements were successful in its ultimate induction into the Indian reproductive frame, its effects are often stunted by socio-cultural, religious and economic stratification.

Bagchi dwells in case studies to describe how class, caste, religious biases can create hurdles for women to access technologies which profess to guarantee them their reproductive rights. Lack of infrastructure often led these women towards exploitative rackets.

women’s education was encouraged only to equip women with the efficiency to raise sons for the nation.

Reproductive technologies get translated into new age trappings for women who have to bear the brunt of the obnoxious son-preferring practices which hurt them irrevocably. Negligence towards the girl child and female feticides are rising to generate a glaring difference in sex ratio. This transforms motherhood into a coercive instrument thwarting all human elements that it could nurture.

The very idea of the family sometimes becomes an instrument of torture and violence which again targets the female body for experimentation. The capitalist idea of a ‘happy family’ makes children a necessity which drives infertile couples to fertility clinics. Here the woman, willingly or unwillingly, turns herself into an object of exploitation for the consumer-driven free market economy.

Genetic mothering is the new language of female oppression while surrogacy, being promoted by public figures, easily becomes exploitative of underprivileged women. While it promises happiness – this commodification of the birthing process tends to become more exploitative in the hands of patriarchy for which women have to dearly pay, Bagchi states.

Just to say that motherhood gives women a space of their own is glossing over the nuances that an institutionalised limitation creates for an endearing relationship. The pseudo-glorifying strategies continuously render mothers helpless, dissolving any form of mobilisation for which they might have to go against the norm. The notion of motherhood must be more accommodating and emancipatory in order to be an enriching experience for the mother, who isn’t necessarily female or biological; and the child, who isn’t necessarily male or biological, and also for society at large.

Also Read: Jasodhara Bagchi: Flame of Resistance And Freedom | #IndianWomenInHistory

Featured Image Source: Amazon and Purnaba

About the author(s)

Priyanka Chatterjee is a mother, researcher, and academic. She lives and writes from Siliguri. Her articles have appeared in Feminism in India, LiveWire, Himal Southasian, Sikkim Express, among others. She can be reached at site.surferpc@gmail.com and is on Instagram @priz_chatt

This is why feminism is becoming a turn off. It is completely driven by ableism and doesn’t recognize the majority will not just join in their consumerism driven feminism culture.