Posted by Sneha Khaund

There’s a photograph in my phone of my mother and grandmother in the garden on a winter’s day. My grandmother is laughing, eyes twinkling, I can almost hear her effusiveness. My mother squints her eyes in the sunlight and frowns at the lens. My grandmother died a couple of months ago and it’s been a handful of years that my mother passed away; I cannot write about one without thinking of the other.

One could say they were different as light and day. My grandmother’s life reads like a list of achievements: a scientist with a teaching career spanning decades and a singer connecting generations across radio airwaves. She retired from her university professor role characteristically, setting up music, dance, and art schools that she was minutely involved with till the very end. One could attribute these activities to love for the arts and singing, but as she gravely told me many times at the beginning, she felt like she needed to constructively contribute to the new neighbourhood after having left behind the vibrant university campus life upon retirement.

How could I write about women whose very existence the official sources barely acknowledged?

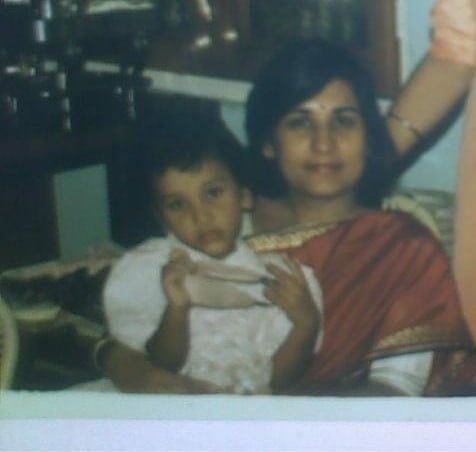

My mother has disappeared like a dewdrop in the morning light. You will not find her on a Google search and you will have to imagine away our father’s features to see my mother smiling in my face and my brother’s. Perhaps it was parental rebellion: she refused to drive, finish her postgraduate degree, get a job, send her kids to the dance, music, and art schools, like her mother insisted she do. Occasionally she would ask the maid to help her organize her closet after my grandmother and aunts were terribly agonized about the chaos that spilled out of it. Now it remains frozen in neatly folded layers, chaotic only in the multitude of colours and fabrics. I use the memory of the senses to love her still, the texture of her warm, lined hands cupping mine, and the brightness of lipstick that has since dried up in their tubes.

My mother and I

I think of my grandmother after my mother’s death, standing tall in her elegant, slim frame, and the grief she wanted to communicate. I couldn’t understand the anguish trapped in starched cotton and silk, pinned at the chest, maybe I feared it. Perhaps she will be remembered beyond her family and friends, she will leave behind a legacy that hopefully will be inspirational. I wonder though if she worried whether her daughter will be forgotten. Like my grandfather’s mother who died in childbirth, remaining only in a pair of heirloom earrings. Or my father’s mother, who nobody remembers as inspiring but I can see her outline on the verandah through the living room windows, poring over magazines and books and suddenly all I want is to be left alone to read too. Death bodes finality, possibly more so for women but it doesn’t have to be so.

History writing is cruelly aligned towards men. Perhaps it follows life itself as patriarchal society is structured along the male line. So while it is all too common for property to be inherited by the male descendants and keep the socio-economic roots of patriarchy thriving, it is also the imagination of time that is dominated by men. The way we think of historical time — linear, active, event-determined — tends to paint men as architects and actors. For instance, the FII article on the women shapers of the Indian Constitution is path-breaking simply because it sheds light on the gendered biased perceptions of the nation coming into being, and how complete the erasure of women has been even in recent history. In literary history, Virginia Woolf contemplates the literary career or lack thereof of William Shakespeare’s fictional sister, Judith, who would have been denied equal access to education and public spaces which in turn stifles her creative genius. This ruminative section in A Room of One’s Own sheds light on how talent and achievement and even enduring memory that celebrates and commemorates these are tainted by gender inequality.

History writing is cruelly aligned towards men.

The obliteration of women from memory and time is all the more profound when it comes to women belonging to oppressed castes. This is not because oppressed caste women are not remembered by the community, but it is elite nostalgia and public memory that forms the mainstay of dominant discourse. In contemporary history alone, Radhika Vemula has relentlessly campaigned against forgetting Rohith Vemula and Sujatha Gidla has sought to archive Telugu Dalit memory and incisively examined the way elite nationalism has precluded its forming the national imaginary in the book Ants Among Elephants. Reading Coolie Woman by Gaiutra Bahadur has been very influential for me in shaping these thoughts. The book follows Bahadur’s journey to trace her family’s history from a village in Bihar to indentured labour in the sugar plantations of Guyana through her great-grandmother. She writes about the difficulty of constructing such a history, ‘How could I write about women whose very existence the official sources barely acknowledged?‘

Bahadur turns to alternative, unofficial sources such as oral traditions and visual clues to uncover the ‘stolen voice’ of a marginalized community and of her great grandmother. So does Piya Chatterjee in A Time for Tea to present a feminist, ethnographic critique of the tea industry through conversations with the women labourers who oftentimes are barely literate and suffer the indignities of belonging to a marginalized community. There is a seemingly unknown vastness of history that is being grappled with by such scholars. For it is not simply exceptional women whose stories need to be shared, but also the ordinary, the everyday of women.

It is not simply the exceptional women whose stories need to be shared, but also the ordinary, the everyday of women.

Perhaps exceptional women like my grandmother will be remembered respectfully. Others like my mother, who did not have an extraordinary list of achievements standing in for a life lived, should be too. In patriarchal ecriture, historical time is the domain of men where certain exceptional women’s achievements are celebrated, the rest of womankind seemingly not worthy enough of historical mention. I look forward to the subversion of this system and alternative ways of narrativizing so that women’s stories, their lives, like my mother’s, are passed on and cherished.

Also read: Why Do We Not Acknowledge Mothers As People First?

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.