Moral panic.

The term was first popularised by a sociologist called Stanley Cohen in his book Folk Devils and Moral Panics. Published in 1972, the book defines a peculiar phenomenon: “a condition,” says Cohen, “episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests.”

It’s a strangely evocative term, even if Cohen’s restrained, scholastic language doesn’t quite capture the nuances of the two words. His description carries no judgment for the participants of the phenomenon – as indeed it shouldn’t if he wasn’t to lose his academic credibility. It doesn’t capture, I think, the righteousness of morality; the madness of panic; the smallness of being at the confluence of the two.

I should know. I’m the object of one.

***

For years and years I’ve dodged around the word ‘fat’.

“You’re healthy,” they say. “You’re strongly built”. “You’re chubby.” “You’re sweet.” “You’re normal only.” I’ve learnt all the euphemisms by heart now.

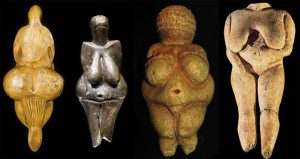

Venus Figurines of the European Palaeolithic Era | Image Source: Ancient Origins

For years, I’ve looked in the mirror and seen, not a person, but a being encased in fat – the rolls and rolls of fat that hid my actual body that would emerge from it one day.

When I was 6 years old, I weighed 35 kg. This was ‘far too much’, I was told; I had friends that weighed in the twenties, or less. To this day I don’t know if this was true or not; I just believed my mother when she guiltily admitted it. “You’re just a little healthy,” she said. And I was vaguely conscious of having done something wrong, and ashamed for it.

The all-girls’ school I went to in Kolkata didn’t have any games. The PT classes consisted of us wearing different shoes and moving our arms in circles next to stationary desks and chairs within the classroom.

For years, I’ve looked in the mirror and seen, not a person, but a being encased in fat.

By the time I was ten, we moved to Mumbai. “So big?!” boomed my new Vice-Principal, when she saw me. I was sent off to the medical centre to get some checks done. The girl at the counter wrote ‘Age: 16’ on my form. The doctor took one look and said, “What? You look hardly older than 10!” When we stepped out, my mother said, “See? Your face still looks young.” On an office picnic trip, I remember saying, “I wish my breasts weren’t so big”. And she replied almost immediately, “Hyan, so do I.” I’d known she would. I’d said it because I knew that was what she wished, too.

That picnic I didn’t mingle with anybody. The one time I went to dance, I came back happy and panting and asked my parents what I looked like. “Prochondo mota,” said my dad, after a beat, and my mother agreed. Very fat. There was something on his face, a look I’d seen before, that meant nothing good but I didn’t know how to name yet. I’d come to realize later that it was disgust.

***

I remember the exact moment in which my relationship with food changed.

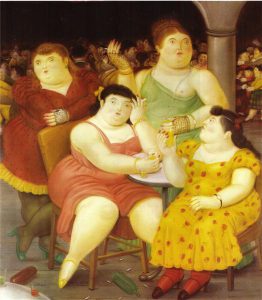

‘Four Woman’ – Fernando Botero (1987) | Image Source: WikiArt

It was our first weekend in a new city; the flat was strange and our furniture hadn’t arrived; our new cook maushi had just left. And she had cooked pulao and chicken and left it on the floor of our kitchen to cool. And I sneaked in, and I picked up a single piece of chicken – succulent, soft, the ultimate Bengali comfort food. And I went ahead and chewed it, and it felt good.

And all the while, I knew I shouldn’t. There was a knowledge that this was monumental, that this would change something fundamental in me.

There’s a Bengali word for it. Lobh. Greed. Or something like greed, with a hot pit of shame attached.

I don’t remember the first time I was called lobhi. A greedy, greedy child, never knowing her shame, never knowing her self-respect, never knowing when to stop.

When I was around twelve years old and in my angriest pre-teen phase, the idea suggested a different English word to me. A whore. I remember writing in my diary, hot tears blinking in my eyes, falling onto the page: I feel like a whore, I wrote, whenever I eat. Like a greedy woman grabbing at something sinful, something she shouldn’t have.

The word would come back to me when, years later, I would write about struggling to wear makeup and not feel like I was doing it to attract attention to my body- this lumpy, ungainly, fat body, with huge swinging breasts and great big buttocks that people could see when I walked. I can’t wear kajal, or lipstick, or that top, I’d think. I would feel like a whore if I did.

I feel like a whore, I wrote, whenever I eat. Like a greedy woman grabbing at something sinful, something she shouldn’t have.

***

By the time we came to class 5, I weighed 65 kgs. I had gained 30 kgs in a single year.

My PE teacher, a nice man, was alarmed. He told me, gently I remember, that something needed to be done.

I joined tae-kwon-do. I loved martial arts. I loved the sheer grace and power of it. I think it came from my dad’s love for Bruce Lee movies, which he passed down to me even though we’d never watched one together. By class 7, although initially I was so nervous that I’d feel nauseous before every class, crying, screaming and begging not to go, I’d worked my way up to a red belt.

I’d changed schools by then. The school was just being set up and my friends and I gravitated towards each other with ease. I got on well with my teachers. I went to lots of competitions. I even started playing handball.

It was the happiest year of my life.

And then we moved.

***

I will skip over the next five years.

I can’t look back – not yet. Some things are best left alone, unstirred, wrapped in their own silence, until one is sure one can face them.

‘Drawing 50’ – Namio Harukawa | Image Source: Beuys On Sale

It’s difficult to remember how much I hated my body – viscerally, elementally. How much I thought I was a disease, a failure in body and in mind. Every inch of my body, from my skin to my hair to my stomach – oh, how I hated my stomach! – to my arms to my cheeks and my face. It writhed in me, that hate, like a snake, lashing out and tearing me from inside out. It bled everywhere. It strangled me, every minute, every day. My body disgusted me. I was too much; I spilled over everywhere and was so ugly I offended people: and I did nothing about it. I was lazy. If I dressed up, I was so nervous I could not talk; people were calling me a slut, I knew. When I didn’t, I was a modern Samsa – an insect in a shell.

By the age of 16, I no longer believed I was capable of being loved.

I once described it as being stuck at the bottom of a well – you can hear what is going on outside, but you no matter how much you scream, no one hears you.

One day, I woke up and I realized I could not look at myself in the mirror anymore.

Even now when I look back on my pictures of the time, there’s a sense of disconnect, as though I’m looking at someone else’s body, someone else’s memories.

By the age of 16, I no longer believed I was capable of being loved.

***

I’m particularly drawn to images of fat women. I remember the first time I looked at an image of Venus figurines, and for the first time in my life I found myself represented in art. She looks exactly like me, I thought, looking at the drooping breasts, swollen stomach with every fold lovingly moulded, a thick vagina and endearingly stubby little legs. And I felt, not shame, but pride, and I blinked. It was an unfamiliar sensation.

I remember the first time I saw Fernando Botero’s paintings. They made me made me laugh in a way that was initially uncomplicated but later came to signify what I thought Botero had intended them to be: a physical representation of moral corruption, a form of visual irony or satire. To this day I’m slightly unclear about the exact meaning of those images, especially after I found out that he was influenced by Rubens, whose depictions of fat women are famous for their inviting sensuality.

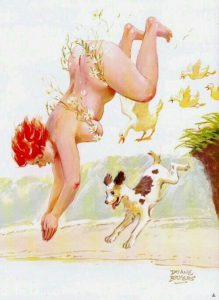

Hilda – Duane Bryers | Image Source: Pinterest

I remember the first time I encountered Namio Harukawa’s illustrations of women who looked a lot like me. They did not satisfy: the aim of equality was not to be equally objectified but equally desired, and his work walked a dangerous tightrope between the two. They still felt like something I wanted to be, though: powerful, sensuous.

I remember the first time I met Hilda, Duane Bryers’ pin-up girl, in her varied moods. She was never simply frozen in the exact pose most advantageous for the male gaze, but laughing, playing, angry, embarrassed, swimming, jumping over puddles with her dog, engaged in so many activities I thought I could never do.

And then I met bisexual art deco artist Tamara de Lempicka, who presented to me a revolutionary way of being fat, being fat in a way that was neither pinned in the male gaze, nor objectifying, nor satirical: merely sensual, and beautiful, with a softness that was sincere. It felt like me.

***

Images are powerful and self-reinforcing, and self-images particularly so. But they do not speak in a vacuum – their interpretations are contextualized in pre-knowledge. Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows is simply an impressive painting of a field with crows, until you come to know that it was the last painting he finished before he died- and then it’s a picture of isolation and death. Images often change their meaning in accordance with what you already think.

When I first started posting my own pictures on social media, it felt like resistance. This was in Class 9, and I was afraid. In the first selfie I put up on Instagram in my first year of undergraduate studies, I look innocent – calculatedly so. I was afraid to look sensual, like I was ‘inviting attention’ – like a ‘whore’. The internet is a public place, and the rules that governed my body in physical places also applied here: my body was not my own, and the threat of violence and violation was omnipresent. In attempting to present myself in it, I was subverting the narrative, and I was terrified of what the consequences could be.

Over the years, my appearances in pictures became more and more frequent – from maybe a dozen or so a year to dozens a month, on friends’ profiles and on my own. I took more pictures myself. I allowed people to take more of me. I became comfortable with being represented: with being seen, by others and myself.

I’m hardly the only one to use social media as a platform for individual empowerment. When you hate the sight of your own body, a community of people reassuring you that you are accepted is the closest one can come to hope.

***

The first step to taking back control was through fashion.

What I wore defined the way in which I presented, and therefore represented myself. It was my way of reclaiming what was left of me. It gave me a degree of bodily autonomy I never thought I could have.

When you hate the sight of your body, a community of people reassuring you that you are accepted is the closest one can come to hope.

Fashion became my way of resistance against becoming a commodity. It allowed me to drive a narrative that I had always drifted along with. I controlled how I wanted to present myself, and stopped being controlled by others. I was not that self-effacing girl who looked into a mirror and saw nothing anymore.

***

‘Blue Woman With A Guitar’ – Tamara de Lempicka (1929) | Image Source: ArtStack

As women, we’re encouraged, to take up as little space as possible: to speak in hushed tones, to cover up our body, to keep our heads down and our eyes to the ground. We’re hidden behind pallus and curtains in separate quarters; we’re locked into hostels and homes; we’re asked not to do anything to draw attention to ourselves, our outlines, our actual physical existence. We’re encouraged to become smaller, invisible, inaudible, illegible. We’re taught, in other words, to efface ourselves, so that when we look into the mirror, we see nothing at all.

Fat women are constantly reminded of how much we do not fit this narrative – and that, I think, is where the real anger comes from. Fatness is not merely a physical threat – and how could it be when it cannot be an epidemic, after all, since it is not infectious? It is a moral threat, and a moral failure. A fat individual represents the ability of a woman’s body to ignore patriarchal expectations and still survive; she represents vice, because she violates these expectations; it is this survival that thus must be negated.

***

Women’s bodies are repositories of cultural significations. When capitalism had begun to emerge as a burgeoning economic structure around the Renaissance, a fat body represented luxury and wealth, the ability to possess that little bit more that others could not afford (hence, Rubens’ obsession with them). Now the opposite is true and thus the opposite is virtuous: ‘fitness’ and its pursuit is morality, perhaps in reaction to the previously-held perception.

Impossible beauty standards are not a new form of indoctrinated self-limitation for women. The idea of equating a particular kind of physical appearance with moral supremacy is not new either: beauty and ugliness have been equated with virtue and vice respectively throughout human history; just take a look at our myths (Sita and Shurpanakha come to mind). The abhorrence of fat women is merely the current cultural manifestation of this nexus of capitalism and patriarchy: in Cohen’s words, “something which has been in existence long enough, but suddenly appears in the limelight”.

***

So when a random man comes and hands me a weight loss card on a Durga Puja morning in an empty Metro Station, pushing into my personal space even when I explicitly tell him that I do not want to talk, he is not concerned about my health. How could he be, when he has not spoken to my gynaecologist or my general physician and therefore does not know that my body is perfectly fine? How could he be, when he did not know that I had been in counselling for severe clinical depression for four years by that point, and that I did not see the need to feel less fat anymore? How could he make a judgment that my health is failing when he knew nothing about it?

This automatic equation, that to be a fat woman must mean that I am unsatisfied with myself, or that I am unhealthy, is what I am fighting.

A fat individual represents the ability of a woman’s body to ignore patriarchal expectations and still survive.

It is a daily battle. It splits you down the middle. But I’m done being the punch line, the lowest common denominator that the public can laugh at now that they are held accountable for their mirth at racist and sexist jokes. I’m done with my body being used as a symbol of a public health crisis, regardless of the reasons for which it is fat, and regardless of its state of health. I’m done with the narrative of my own body being seized from me.

I’m only going to get more and more fabulous from now on, physically and intellectually, or at least try to, and I’m going to do it all while being – gasp! – fat. And if this subversion of the order of things causes society to fall apart, it’s no longer my business – or my fault. The onus to do better is on you.

Featured Image Credit: Kristy Milliken

About the author(s)

Rushati Mukherjee is a Producer of the news podcast BBC Minute India, for BBC World Service. They have written for national and regional outlets as a freelance Features journalist. They are on the Advisory Board of the British Council's international journalism conference, Future News Worldwide. They are also a translator and a poet, and have been an official blogger at the Jaipur Literature Festival. They can be reached at @rushatim on Twitter.