Posted By Ayushree Nandan

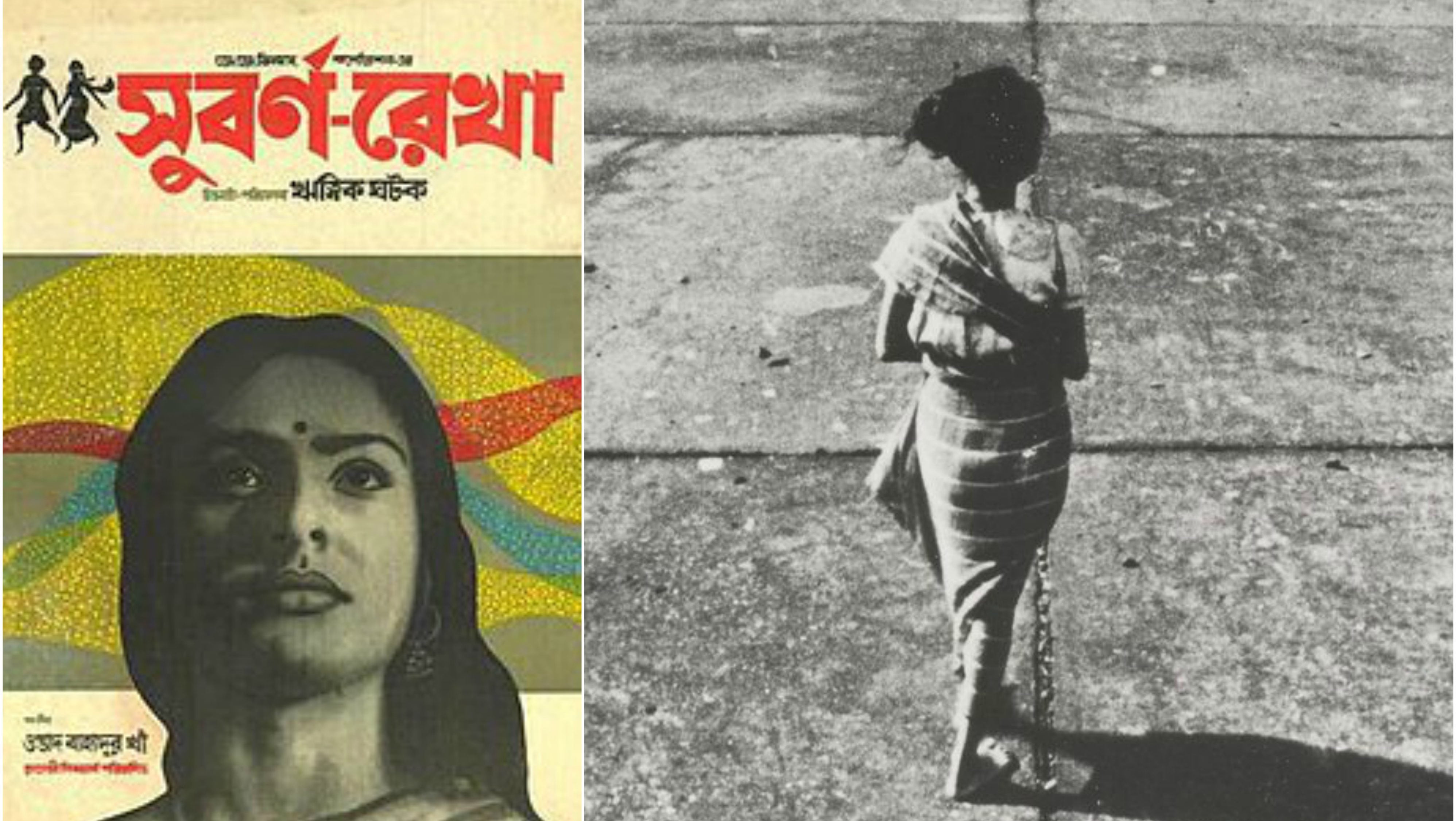

53 years ago, Subarnarekha (1965), an Indian Bengali film and a part of Ritwik Ghatak’s trilogy including Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960) and Komal Gandhar (1961), featured the lives of Bengali refugees in the aftermath of partition of India.

The story of Subarnarekha revolves around Sita, a Hindu refugee child at a refugee colony with her elder brother, Ishwar where they meet Abhiram, a boy from the lower-caste. Despite resistance faced by the upper castes at the camp, Ishwar decides to take care of Abhiram, and travels to a small settlement called Chatimpur with the kids to pursue a job at the factory. As Sita and Abhiram grew up, they wished to marry each other. However, when Abhiram’s caste identity was exposed in society, Ishwar stood against their union, dreading it will impact his job. When he arranged a wedding for Sita with a boy from an upper-caste family, she ran away with Abhiram to start a newly married life in Calcutta, while being completely disconnected with, and abandoned by her brother.

With deftly etched camera angles and characters, the craft of Subernarekha is the protagonist, Sita, who is symbolic of Ghatak’s emotions about political instability and displaced lives, that remains immortal in the world of diasporic cinema. Her character is a portrayal of refugee politics intersected with gender and caste-system, paving way for many social constructs in India that we see today.

Sita’s character questions identities, since her constantly displaced identity as a refugee is intersected with her gender and the role she plays in society. Due to the caste-based stigma, Ishwar compelled Sita into marriage, against her will and attempted to give her an identity which was suitable for his social position. One of the powerful scenes in Subarnarekha, however, was the courage that Sita and Abhiram showed when they married each other despite the caste conflict that floats in the post-colonial India. Inter-caste marriages and relationships, even today, are sensitive issues to touch upon in a vast majority of South Asian countries, and Sita’s rebellion challenged this notion.

In spite of owning her decision, Sita still wasn’t the owner of who she wanted to be. She was once again seen as Abhiram’s wife, a new identity that the story thrashes her in. Her assignment for household chores with added caretaking of her son and husband remained the same, and with that, her changed identity was conditioned by society.

Subarnarekha is enveloped with the hyper-visibility of the caste system that existed in Bengal even during the reign of the Britishers. Right when refugee colonies were being set, the lower castes were dislocated from the settlement on the fascist orders of the landowners. The characters in the movie repeatedly justified casteism as an ancestral responsibility to be fulfilled. “If we don’t take care of the virtue of our castes and mix it with them (lower castes) instead, what are we left with?”, asked Ishwar’s friend from him at the beginning of the movie.

While the process of Abhiram and Sita’s marriage was not easy, the aftermath was even more difficult. Owing to their inter-caste relationship, the couple was compelled to live in slums of Calcutta with their son, little Binu, and counted every penny of the fortune that Abhiram brought to the household as a bus driver.

Due to the caste-based stigma, Ishwar compelled Sita into marriage, against her will and attempted to give her an identity which was suitable for his Social position.

Sita mentioned that she’d love to sing for others and earn money for the household, an idea that was brutally dismissed by her husband. However, the scene was more fragile than one thinks it is. While the interaction obviously indicated how Abhiram controlled Sita’s decisions, now that she was his wife, it also brings out the oblivion Sita, coming from an upper-caste family in Bengal, had been living in. A country that was stricken with the despair of partition, equated a women’s ability to sing or dance with sex slavery, a type of work that the lower caste women from the new settlement of Bengal were involved in was something that Sita coming from a more affluent background was completely unaware of.

However, following Abhiram’s death, Sita started working/singing in a brothel and was conditioned to have her identity changed yet once again, and this time, to something that was willingly proposed earlier by her but was rejected, revealing the contradicting colours of the era she lived in.

The gender ratio in Subarnarekha is quite alarming. Sita and her neighbour in Calcutta having minuscule attention in the movie were the only evolving women characters over a plethora of male characters in the story-line. Such an evident inequity represents the condition of women in the post-colonial era with minimal social visibility whether it was at workplaces, leading spaces at refugee colonies, education, and even walking down the streets in the broad daylight. While the gender roles were synonymous to most of the aspects of how a brown society functions, they are also reflected on the patriarchal effect of identities among refugee women, much of which impacts and is followed by the individuals even today.

The irony of Subarnarekha is that despite the hustle and bustle of male voices in Bengal, the protagonist of the movie remains Sita, a woman. The story-line is etched around an obvious satire to not only represent the politics in gender identities through Sita, but to also mock at the patriarchal values rooted in the foundation of the society. Another reason is that Sita, while as a woman, remained captivated within the realms of socio-economic gender roles, nonetheless, attempted to break it several times. Whether it was having fiery conversations with her brother, owning a choice, rebelling against social injustice, or simply singing by the field, she used all opportunities to create a stronger pathway for herself, and many more brown women from the next generation, that are yet to arrive, where they have the agency to own who they really are. Her most commendable yet saddening tool to achieve the direction was death.

When Sita met Ishwar at the brothel, she killed herself overpowered with anxiety and shame, before he could see her properly. As Ishwar lived in the guilt of being the reason for his sister’s demise, Sita’s death explicitly builds a case for feminism amidst the grief of her lost life. The sight of Sita’s body on the floor, the exaggerated sound of her breath next to the kitchen knife, and the big close up of her painful blinking eyes marked the devastating theme of ‘lost home’ associated with the partition. Sita, as a refugee woman, did not have her identity fully in her control regardless of the number of rebellious steps she took. Sita making a move to kill herself highlighted that she will never get out of the patriarchal control, and her death was the only pathway to freedom she had.

Also read: Suchitra Sen: From Mahanayika To Recluse | #IndianWomenInHistory

Moreover, the character has been named Sita, to bring out this exact emotion in the movie. Sita is a name that has been used for characters in Swayamvaram and Ramayana as well. The similarity among all 3 characters bearing the name is that they never have a happy life. Despite marrying men they like, they still spend time in exile, suffer in solitude, and are raised eyebrows at by the society as well.

The irony of the movie is that despite the hustle and bustle of male voices in Bengal, the protagonist of the movie remains Sita, a woman. The storyline is etched around an obvious satire to not only represent the politics in gender identities through Sita but to also mock at the patriarchal values rooted in the foundation of the society.

Subarnarekha’s expression of ‘lost home’ and ‘recreation’ is constantly felt among the actors. The beginning of the narrative showed new life colony as part of the new settlement out of deprivation in the refugee camp that transits into the emergence of Ishwar’s travel to Chhatimpur village to start a new wheel of job and life. Subarnarekha in itself is a portrayal of recreating the world with innocence over middle-aged struggle filled with casteism and social constructs, with a series of uncanny exchanges between Sita and her brother.

Sita’s songs often expressed tragedy, a theme crucial for depicting the emotions involved in partition. While Sita sang, she grieved for the displacement of humans, a sad turn of events following the episode of partition. Just as how humans are forced to live, Sita too was doomed to grow up, as she continued adding gloom to her songs the entire life she was conditioned to spend.

However, Sita’s lyrics took a new way when she was with Abhiram, into simple ecstatic moments broken away from the realms of the movie. Sita’s happiness was bundled up at Subarnarekha, a paddy field where she spent joyful memories growing up and playing with Abhiram amidst the crisis. She sang along “Aaj Dhaanar Khete (the paddy field today)” for her favourite place in the world that represents new life, celebration, and unison. Blessed with a serene voice, Sita while depicting the condition of the crisis, is also a gentle force that addresses the harshness in the surroundings.

Also read: Rituparno Ghosh: Making Us Comfortable With The Uncomfortable

The beauty of the misery in Subarnarekha lies in the setting and the characters, and most importantly lies in Sita, the character who not only speaks for human sentiments attached to displacement and partition, but also sets a foundation for lost identity of a Hindu woman intersected with refugee politics; an identity that speaks for many women in the post-colonial era.

Ayushree is an independent writer who reports on people, places, culture, food, and intersectionality. She has also worked closely with education and people management. You may get in touch with her on Instagram and Twitter.

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.