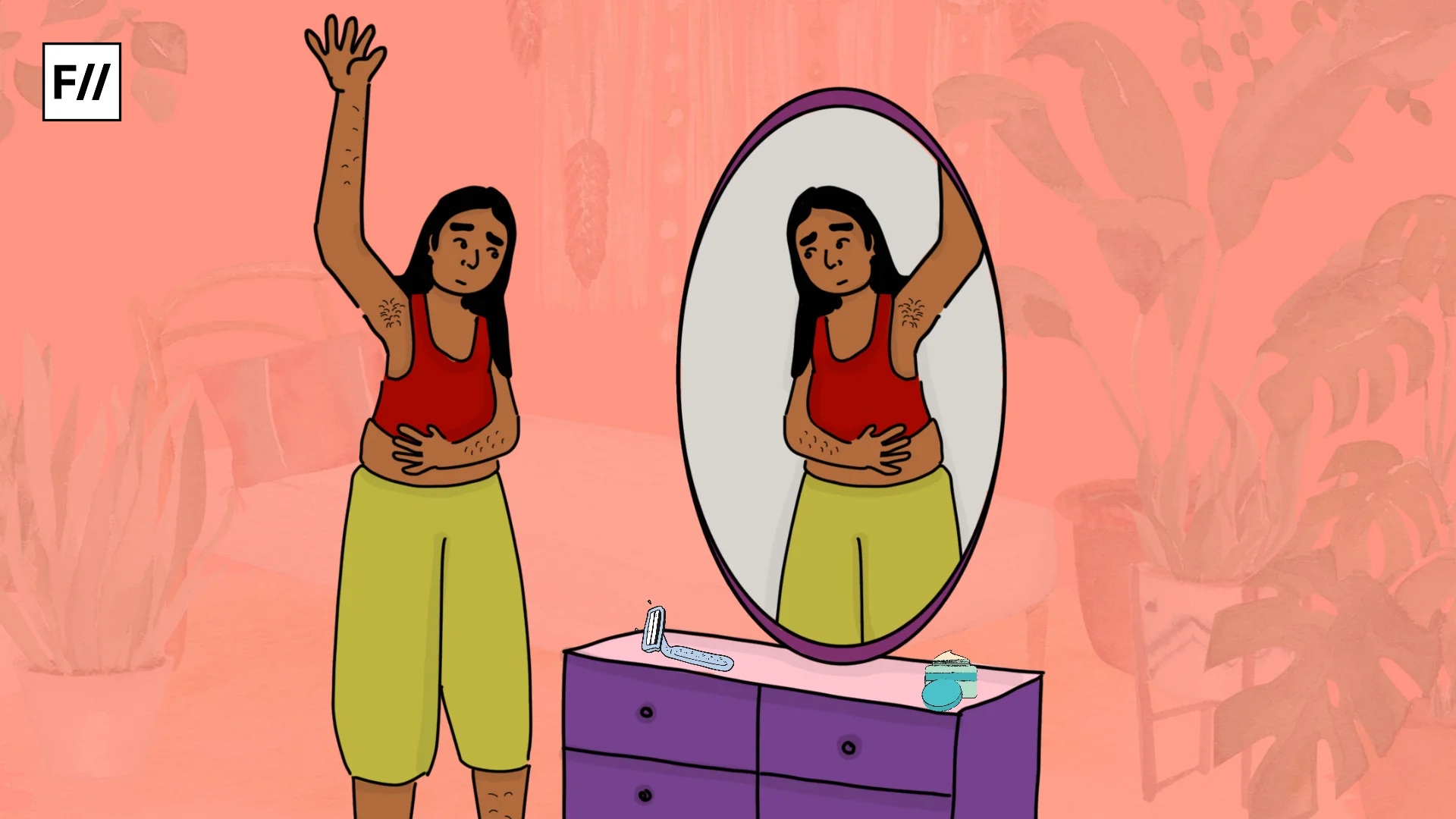

Editor’s Note: This month, that is July 2020, FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth is Feminism And Body Image, where we invite various articles about the diverse range of experiences which we often confront, with respect to our bodies in private or public spaces, or both. If you’d like to share your article, email us at pragya@feminisminindia.com.

The COVID-19 lockdown has been an incredibly difficult time for all of us. The suddenness of it all, the lack of preparedness, the hoarding, the debilitating migrant crisis, the uncertainty—we’re truly downplaying the effect it is having on us in every way. Our brains are struggling to compute why we’ve suddenly broken our routines. Our bodies are confused because we’re not brushing our hair or bathing as regularly as we should. We’re watching the news every day, only to see the number of cases skyrocket with no dip in sight. Our daily routines now involve washing our hands till our palms start to itch, and our outfits (if we dare to get out of our night clothes) include a very important accessory—a mask. Our senses are tired from constantly fearing touching a stranger or a surface by accident. From being out on the streets protesting for over 100 days in the biting New Delhi winter to having no physical contact at all, our lives have permanently changed.

So if you want to cope by making some damn banana bread, you go make that damn banana bread.

I was talking to one of my professors on the phone a while ago, asking her how she’s been coping with the pandemic situation. She was calm. “I went to the market in search of some baking powder, but they were completely sold out,” she said. “I tried at least three different stores, and all of them were out. How much are people baking?” she said, and we laughed. A couple of days before that, I had gone to a supermarket to buy baking soda, the most widely available ingredient—they were out of stock.

Over the lockdown period, I’ve seen pictures and videos of people finding temporary joy in making desserts—mostly chocolate-based—as opposed to savoury food, and the pattern is not lost upon my logic. Our bodies are asking our brains, triggered by the thought of not knowing what’s going to happen in the future, to produce feel-good hormones. Baking with chocolate gives us joy because eating chocolate releases happy hormones. What we’re craving isn’t chocolate—it’s happiness. It’s really that simple.

But someone must ruin this fleeting moment of euphoria.

Also read: Why You Can’t Love Yourself Into Losing Weight

As if switching from app to app and going around in circles aimlessly—as most of us have been doing more than ever during the pandemic—wasn’t bad enough, it has now also become a site of major guilt-tripping. Why, you ask? Everywhere I look, I see someone or the other preaching about how it’s important to stay fit during this time, and demonstrating it with incredible zeal no less. Every second Instagram story or Facebook post is a not-so-humble brag about the user’s fitness regime, and a not-so-subtle dig at people who can’t or don’t want to have one. You might think I’m being needlessly critical here, but hear me out—it’s not a silly coincidence that half your Instagram followers are fervently baking banana bread, and the other half is shaming them for eating it.

Every second Instagram story or Facebook post is a not-so-humble brag about the user’s fitness regime, and a not-so-subtle dig at people who can’t or don’t want to have one. You might think I’m being needlessly critical here, but hear me out—it’s not a silly coincidence that half your Instagram followers are fervently baking banana bread, and the other half is shaming them for eating it.

A popular fitness and wellness platform recently boasted of $1 million in monthly revenue in May, owing to a surge of app downloads since the lockdown. Many such apps have seen an increase in downloads and subscriptions. Sure, the increased demand for fitness apps can partly be attributed to the shutting down of gyms, but the narrative places importance on something else—the fear of getting fat. Influencers, fitness enthusiasts, trainers, and coaches are milking the guilt that has come our way along with pandemic-induced stress eating, reminding us that if we continue to find joy in food, we’ll get fat—and that, somehow, is infinitely worse than contracting a virus and staying isolated from every human being till we make a recovery, with no immediate emotional support.

Nutritionists are selling N-day detox plans with guarantees that the buyer will lose a certain amount of weight within that time, marketing it as “lose the lockdown weight”. There’s a certain condescension in messaging like this. For starters, it’s assumed that a person has gained weight during lockdown only because they’ve been stuffing their faces with food, which explains the need to add a ‘detox’ as a selling point. Second, it’s presumed that a person who has gained weight during lockdown absolutely must want to lose it. Weight gain is seen as a direct result of gluttony, even if it may not be so. Essentially, then, fat people are seen as unruly, out of control, gluttonous beings.

Some people would argue that being fat isn’t exactly great when you’re fighting a virus, since obesity can compromise the immune system and its response. That’s not necessarily true—several obese people have perfectly functioning internal organs, and there has been no proven correlation between obesity and COVID-19. Besides, statistical data from China has shown that men are more likely to contract the virus than women because they indulge in socially sanctioned smoking in larger capacity, which can compromise the ability of their lungs to do their jobs. But I’ll be damned if I ever saw a detox plan that says “lose the lockdown smoking habit” and promise that they’ll go down from 10 cigarettes a day to 2. Doesn’t sound as appealing, no?

For starters, it’s assumed that a person has gained weight during lockdown only because they’ve been stuffing their faces with food, which explains the need to add a ‘detox’ as a selling point. Second, it’s presumed that a person who has gained weight during lockdown absolutely must want to lose it. Weight gain is seen as a direct result of gluttony, even if it may not be so. Essentially, then, fat people are seen as unruly, out of control, gluttonous beings.

Taking advantage of the fatphobia that is deeply entrenched in our psyche only fuels the discrimination that has long been a product of capitalism. That explains the surge of fitness app downloads—most money-making schemes around fitness are aimed directly at fat people, whether they want it or not. People trying to steal the joy of those who want to eat a slice or two of cake often don’t realize how deeply they have internalized their fatphobia.

Imagine this—with the possibility of contracting a disease looming over our heads, some people find solace in the fact that they’re working hard on their bodies so they don’t look fat. This is where ‘biopower’ comes into play—our place in society is as significant or insignificant as the effort we’re willing to put into making our bodies as socially acceptable as possible, nevermind a life-threatening pandemic. The more we show how much we care about not getting fat, the stronger our presence is among the people around us. Fatness is associated with laziness, and laziness needs to be rectified.

Thin people can also be incredibly lazy, but who’s making note of that?

Also read: The BMI Is Not As Heavy-Weight As We Think It Is

Before the phone conversation ended, my professor said to me, “Look, we’re not going to be getting out of this situation anytime soon. What we must do now is prepare for the inevitability that we may catch the virus, and we must plan our lifestyles accordingly.” Logical, I thought. But that didn’t make it any less scary. I may catch the virus, I thought to myself. The alarms in my head started going off. And in that moment, I didn’t think what my body would look like after I made it back into normal life—I thought about the myriad ways I would thank it for saving me. Then, I rewarded it with a piece of dark chocolate.

Featured Image Source: Yahoo Canada

About the author(s)

Kanksha Raina is a journalist based in Mumbai, Maharashtra. With a Master's degree in Gender, Culture & Development Studies, Kanksha is passionate about pop culture, cinema, and sexuality, with a particular focus on women's experiences. In her spare time, you can catch her reading, binge-watching her favourite TV show for the 10th time, or spending time with her cat. She is an alumnus of the Asian College of Journalism.